Most teenagers never get to meet their musical heroes, and fewer still, get to play with them. But when Lenny White was just nineteen, he got to record with Miles Davis on the seminal album Bitches Brew. In this exclusive interview, Lenny – a drummer, composer, producer and educator – talks about Miles, as well as his incredible post-Miles career that includes a string of superb solo albums; joining the jazz-rock fusion band Return To Forever; forming The Jamaica Boys with Marcus Miller; recording with Jaco Pastorius; teaching students about Miles and the Bitches Brew album – as well as turning down the opportunity to play with Jimi Hendrix…

Lenny White with Listen To This, by Victor Svorinich

The Last Miles: You grew up in the 60s and 70s in Jamaica, Queens, New York. What was it like living in Queens at the time?

Lenny White: Most blacks had come from different parts of the country and when they came to New York, they went to Harlem and Manhattan. But when they got somewhat more upwardly mobile, they moved out to the suburbs – Queens is a suburb. My people were not upwardly mobile, but we happened to move to Jamaica, Queens. It was an all-white neighbourhood – we were the first blacks on the neighbourhood.

What was particularly different and interesting about Queens was that a great deal of famous musicians moved to the area – [band leader] Count Basie, lived in Queens, as did [drummer] Roy Haynes, [saxophonist] Illinois Jacquet, [saxophonist] Lester Young, [and singers] Brook Benton, James Brown – there were a lot of people, who at some time, spent time out there. You also had baseball players like Jackie Robinson and Roy Campanella.

When you think about that time period, 1969 was the year when America became modernised – a lot had happened before that. There were the assassinations of John Kennedy, Malcolm X, Bobby Kennedy and Martin Luther King. So there was unrest in the States, but I think things started to change, and music started to morph. Bitches Brew was done in 1969. So, in Jamaica, Queens, we were all young musicians who were being influenced by the music of the times; by all the things that were going on in that time period – socially, politically, economically.

We were children that listened to all these different kinds of musics and wanted to emulate them and wanted to connect with a particular movement. So, my heroes were Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Jimi Hendrix, Malcolm X, Willie Mays, James Brown and Mohammed Ali – there were a lot of black luminaries. Music was shaping politics and politics was shaping music. To be a young black man growing up at the time was pretty eventful. And Jamaica, Queens was a nice place to be. We had basements, so you had a place to practice. There were places for people to come together and work on things – it was a great time.

TLM: You made a number of life-long friendships and musical associates with people such as with Marcus Miller and Bernard Wright during this period.

LW: I was older than both of them [Lenny was born in 1949; Marcus Miller, 1959, and Bernard Wright, 1963]. Bernard Wright played in my band when he was twelve years-old – he was a genius. I had to go and speak to his grandmother for him to be able to go on the road! She trusted me enough to do that. I met Marcus when he was seventeen. There was a mentor to all of us by the name of Weldon Irvine, who had come from Hampton, Virginia and settled in Jamaica, Queens. He was a mentor to all the guys that wanted to play jazz and progressive music. He had a band that everyone was in and out of – Billy Cobham, George Cables, Marcus, Omar Hakim, Bernard, Donald Blackman – there were a lot of people. I gave Marcus his first recording date. He was always carrying his bass around and he came to the studio. I had this piece of music that needed a funky bass line and I said, ‘Go ahead and play,’ and he said, ‘Me?’ I said, ‘yes’ and he played [on the track ‘Egypt’]. Later on, Marcus, Bernard and I formed The Jamaica Boys.

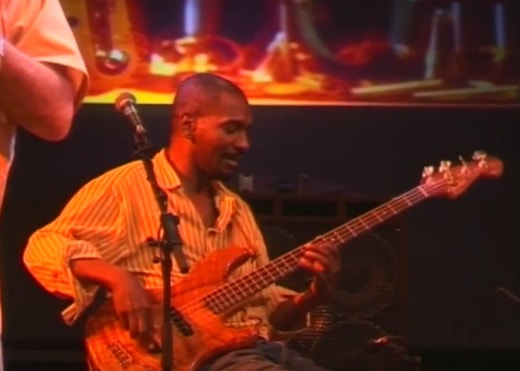

Marcus Miller, Dinky Bingham and Lenny White of The Jamaica Boys

TLM: What I find amazing listening to ‘Egypt’ is that, although Marcus only plays a simple two-note riff and some slides, you can hear that it’s Marcus Miller – he was developing his own sound, even at just seventeen.

LW: He made his mark. When Marcus was in my band, he came up to me and said, ‘Can I talk to you?’ I said, ‘Sure’, and he said, ‘Everything I play sounds like Jaco [Pastorius] to me – Jaco’s my guy. What should I do – I want to sound like myself?’ I said, ‘Keep continuing to sound like Jaco; keep playing like Jaco, because you think you sound like Jaco, but there are things that you do that are your own. You’re going to realise that the more you play.’ And he found a way to come out sounding like Marcus.

TLM: My only complaint about ‘Egypt’ is that it’s too short – it’s got a great groove.

LW: Thank you. As an artist, you create something and you think that it’s great. To some it is, and to others, it isn’t – it’s so arbitrary.

TLM: You started off playing trumpet, because you loved Miles Davis, but I love the story that you have no idea why you moved on to drums. You are also mainly self-taught. What are the advantages and disadvantages of this, particularly when it comes to session work?

LW: Yes, there are disadvantages in every aspect of life, but the disadvantage turns out to be a way through to understanding something. I learnt how to create music before I learnt how to play music. When Miles Davis asked me to do Bitches Brew, there was no music involved. I got into the studio and he said, ‘Think of this as a big pot of stew and I want you to be salt.’ What musical knowledge am I going to call upon to be salt – play a paradiddle? I was given a musical assignment and I had to fulfil it – I had to think about it. So what happens to me when I come to music is that I think about what should be created – what visual musical thing I can do.

I was a painter – that’s what I went to school for, so now it’s just a matter of me painting with notes as opposed to colours [Interestingly, Miles one said, ‘Music is a painting you can hear; a painting is music you can see.’]. I’ve been able to surround myself with people who are forward thinking – that don’t necessarily need something that’s regimented. Although when I played with Chick [Corea] and Return to Forever, that was somewhat regimented, because it was compositions from the perspective of form and certain things.

So I had to learn how to discern that and make it work. There have been ups and downs, but what has happened is that, fortunately for me, I have gotten calls because of what I can do, and there are a lot of people who don’t read music – Buddy Rich, George Benson, Dennis Chambers – they all did pretty well without it.

TLM: And don’t forget Lennon and McCartney.

LW: Hello!

TLM: When you were seventeen, you heard Miles’s Seven Steps To Heaven, which featured drummer Tony Williams. When you discovered that the drummer was only the same age as you at the time, it drove you on.

LW: It gave me a purpose. Being the age that I was and hearing that record and it was someone who was my age that done something I could look up to and respect with the mentor Miles Davis. That was very important to me, and right away, Tony Williams was my guy.

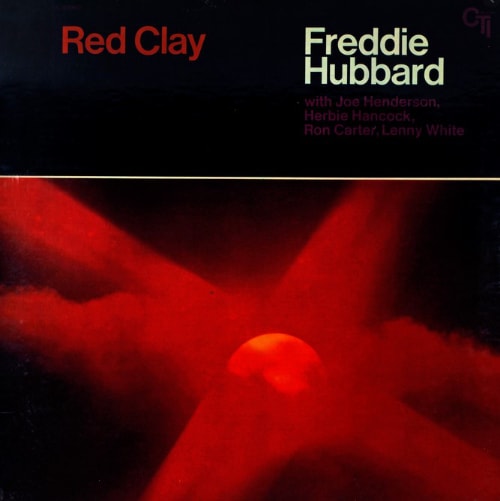

TLM: Tony Williams would play a great role in your life – he helped get you the Bitches Brew gig, and later on, playing on Freddie Hubbard’s Red Clay album. He left us far too soon [Williams died in 1997, aged just 51].

LW: It was a shock, because the potential of what he could have created was vast, because of what he left. The legacy he left is so vast, so you never know what he could have continued to do and how much more his legacy could have been. But because of what he left, it’s still being explored, and that could last forever.

Freddie Hubbard: Red Clay

TLM: You played with Jackie McLean, and it seemed that every drummer in his band at the time, went onto to play with Miles – people like Tony Williams and Jack DeJohnette. Well, you did get the call from Miles, although I gather your mother almost hung up on him!

LW: Miles called and my mother picked up the phone. Miles’s voice was very quiet and I could hear my mother saying, ‘Who is this? What? You’d better speak up, or I’m going to hang up this phone!’ Well, I spoke to Miles and he told me to be at his home the next day for a rehearsal.

TLM: When you arrived at Miles’s home for the rehearsal, there was an incredible line-up waiting for you – musicians such as Dave Holland, Wayne Shorter, Chick Corea and Jack DeJohnette. You’d only been playing drums for five years – what was going through your head and were the sticks shaking in your hands?

LW: It was very interesting. I was like a deer in the headlights – it was pretty amazing. To a certain degree I had it under control. We didn’t rehearse much material from the album – we only did the introduction to ‘Bitches Brew.’ We recorded the album in August and I went back to school. In October, I was in a deep sleep and in the middle of the night, I woke up and thought, ‘I’ve recorded with Miles Davis!’ That’s how long it took to hit me. I had done something that was documented and was going to be there for the rest of the world – I had played with Miles Davis.

TLM: The recording of the track ‘Miles Run The Voodoo Down’ was interesting.

LW: Miles wanted something, and Jack and I started to play what we thought he wanted, and it sounded pretty good. But that wasn’t what Miles wanted, and Don Alias – the conga player – said, ‘Miles, I got a beat that might work,’ and he played the simplest beat. I thought, ‘Man, I can’t believe that Miles wanted a beat that was simple.’ I thought he’d been looking for some Tony Williams stuff and so I was despondent. He said, ‘what’s the matter?’ and I said, ‘I got this opportunity and I didn’t do it,’ and he said, ‘no, no, don’t worry about it. Come back tomorrow.’

TLM: You said a lesson you learnt from that episode was that you need to ask an artist what they want from you, rather than asking yourself what they want.

LW: Correct.

TLM: The process by which the music on Bitches Brew was created was very interesting – it was organic, with fragments of notes; much improvisation, the occasional cryptic remark from Miles and so on. From all of this, you got this incredible music. If you look at the composer credits for Bitches Brew, four of the six tunes are credited to solely to Miles. I’m interested in knowing where improvisation and collective collaboration end, and composition begins.

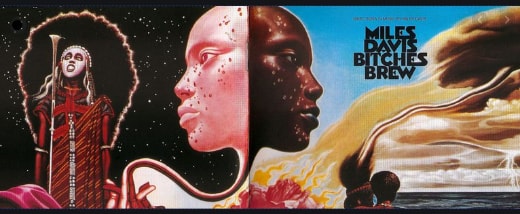

Bitches Brew

LW: That’s a very interesting point. I was talking to a friend about this, and we were discussing the definition of a composer. The definition is shaped by a certain aesthetic. I had a student in my class who said they were very proud to be of a generation where anybody can become a musician. You have to think about that and it brings up a debate. Because no matter how many years Beethoven studied music to create the music that he created, Billie Eilish went into her bedroom and recorded some music, and she’s a musician too. That brings out a very interesting debate because certain aesthetics are housed by whatever century they are created in, and the people that get the art that was created and how they enjoyed it – we’re talking about the twenty-first century now. So, because society and art evolve at a particular point in time, that definition of a composer will change.

There are people who think that improvisation is just doing what’s on the top of your head, but you and I are speaking – we are using language to understand each other. If I said, ‘Sibelius, Watson, drumsticks, drum heads,’ I would be improvising, putting words in random spaces, but using the same language that I’m using to get you to understand. A musician who is improvising has got to a point where they can play their instrument to the degree that you understand what they do: ‘You can play these scales in these chords to make it work.’ They are given these chords and they decide to do something that is outside of the normal thing to do – that’s improvising. It’s also being a composer at the same time you are improvising.

TLM: What are your memories of [producer] Teo Macero and how important was he to the Bitches Brew album?

LW: He was very important to the overall perspective of what Bitches Brew turned out to be. Because Miles had a concept in his head, and with Teo being just a producer, he might have given Miles a [new] perspective to think about or to include things that maybe Miles didn’t think about. But Miles was very hands-on over what he wanted. If you read the book [Listen to This: Miles Davis and Bitches Brew by Victor Svorinch], you’ll see that Miles was very hands-on. I don’t think Teo could have come up with what Miles wanted, but he was an aide in helping Miles translate what he heard into a coherent thing that people could hear and say, ‘Wow!’ If you think about it, there were thirteen musicians; a bass clarinet – Teo Macero wasn’t thinking about a bass clarinet. Teo Macero wasn’t thinking about electric keyboards – Miles had this in his head. I believe Miles had listened to the landscape at the time, which was rock ‘n’ roll and said, ‘I can play rock ‘n’ roll, but from a different perspective – this is what I think it should sound like.’ And that’s what we did, because nobody had heard that music before, and we didn’t know what it was when we creating it. And after we played it, we still didn’t know what it was!

TLM: Bennie Maupin was the bass clarinettist on the album, and he told me that everyone was playing blind – you never heard what you had played or recorded. Do you wish you had had more of an idea of what you had done?

LW: Not all. The genius of Miles Davis was to hear something that nobody else heard, and to surround himself with people, and get them to hear or conceive a new kind of music without knowing how to play it, but by just giving certain ideas to see what the artist comes up and how they form together to create this new puzzle. Nobody knew what it was; he didn’t know what it was. To think, ‘Let’s put this instrument with this,’ or ‘let’s add this,’ or ‘who can I get to play it?’ It was a whole new creative process that was absolutely amazing. To have people go into a room and play something that they didn’t know they were playing and afterwards, still didn’t know what they had done, was brilliant. To take people who are already shaped musically, and take them out of their comfort zone to create this unbelievable music. They still don’t know what it is. They tried calling it fusion, but come on! It was diametrically opposed genres of music that smashed together. Jazz and rock – biff!

TLM: I loved the story about you looking through a window and seeing someone with a copy of Bitches Brew, and you asking them to turn it around so you could see the album credits!

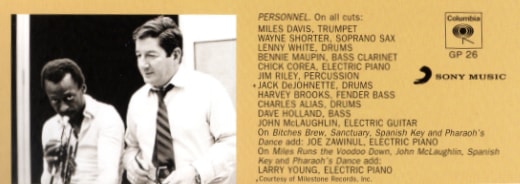

LW: It was one of the greatest album covers of all time. I’m not sure if Miles knew, and I never asked him, but I used to write my name on the back of album covers, just so I could see what my name looked like. The Dave Brubeck Quartet had Paul Desmond, Eugene Wright and Lenny White! When I saw my name on Bitches Brew, I was like, on the moon – it was unbelievable. If you look at the original line-up on the album it says: ‘Miles Davis, trumpet, Wayne Shorter, soprano sax, Lenny White drums’ and then everyone else. I was totally freaked out.

Bitches Brew credits

TLM: Both Joe Zawinul and Bennie Maupin have recalled how they didn’t recognise the music when they first heard Bitches Brew. What was your experience?

LW: I was the only one who heard that album before it was released. Miles called me and had me come over to his house. We sat and listened to the daily rushes of the record. I know for a fact, because on ‘Pharaoh’s Dance’, there was a bridge that is not on the album – there are nineteen edits on it. On ‘Bitches Brew’, Miles played a reference to ‘Spinning Wheel’ by Blood, Sweat and Tears. It was interesting, because on the album, they had looped it.

TLM: It was a closed session and there wasn’t even a photographer present to document the event.

LW: There are no photographs, but something most people don’t know is that Max Roach was at a session. Afterwards, Jack DeJohnette, Max and I rode into Harlem. But I didn’t see anyone else except Max.

TLM: I have got to ask you about the time Miles asked if you would be interested in playing with Jimi Hendrix and you said no!

LW: The deal was this – I was enamoured with Miles; he was my mentor. I didn’t just want to play with Miles Davis; I wanted to be Miles Davis. So when Miles asked me, I wanted the gig with him, not the gig with Hendrix. Now it seems stupid of me not to do it, but I was young, and the fact was that I was going to play with Miles. Lydia DeJohnette [Jack’s wife] was pregnant and Jack was going to stay home with her and I would take Jack’s place. Miles manager Jack Whittmore had called me and I was going to play at [the Massachusetts-based jazz club] Lennie’s on the Turnpike for at least a week, and then Miles got shot [In October 1969, Miles was sitting in a car with his lover Marguerite Eskridge (mother of his youngest son Erin) when a gunman fired five shots at the car; no one was hurt in the attack].

TLM: You have said that you would never have believed that, in 50 years’ time, you would be talking to students about Bitches Brew. But you now teach a course about the album at NYU Steinhardt. What do you think the students have learnt from you and what have you learnt from your students?

LW: The chair at NYU asked me to create this class and I had to find something to teach out of, so I found this book [Victor Svorinich’s Listen to This: Miles Davis and Bitches Brew] and who could be better prepared than me? I was there; I was part of it and I lived it. I walked into the class and realised that none of the kids were alive when this music was made and they had a totally different perspective on music. I was like, “Whoaa! What am I gonna do?” I asked, ‘who would be the four artists that represent your music?’ I’ve been doing this for six semesters and I keep getting the same four artists – Beyoncé, Lady Gaga, Kendrick Lamar and Kayne West.

So, I have to talk about the recording process; what was going on socially; Miles Davis, and how he got to the point to make music like that to kids that listen to those four artists. And Kayne West said he hates guitar! So, you see my challenge. I have learnt a lot about sharpening my teaching skills and the generation that I live in right now. I am a twentieth century musician negotiating my way through the twenty-first century – things have changed. The aesthetic has totally changed. The reason why I made music is totally different from the reason why people make music today. So, I have to bridge both generations and it’s somewhat difficult, but I’m finding more and more about myself and finding more and more about the generation that I live in too.

NYU Steinhardt © NYU Steinhardt

TLM: You recalled how none of your students had heard of Stanley Clarke!

LW: Unbelievable! Here’s a man that has done 200 movies [soundtracks] or whatever, and they don’t know him! He’s an integral musician in the transfer from the twentieth to the twenty-first century. This will probably only come from an inspirational teacher, but students should want to do the research to find out about the musicians that have given this arc that went from the twentieth to the twenty-first century. That’s the way you learn about the music that you want to create.

TLM: Bitches Brew raised your profile considerably, and one of the things that happened was that Freddie Hubbard asked you to play on his album Red Clay, which was very influential. I understand though, that it was ten years before you could listen to the album, because you hated the sound of your bass drum and could hear the mistakes that you made. The bass drum sound happened because [bassist] Ron Carter, who was also on the session, stated that you needed to change your bass drum.

LW: It’s interesting that you talk about that, because last Friday, I was on a zoom call with Ron Carter, Marcus Miller, Darryl Jones, Dave Holland and other bass players who had played with Miles. There were about 800 people on that zoom call and people got from the horses’ mouth what happened on that session!

TLM: I’m interested to know what you thought about the music Miles made in the last ten years of his life.

LW: I think what I got from it, many other people didn’t get. I thought that Miles made a great statement of music being congruous and that music is music for music’s sake. How he played with Charlie Parker; how he played with Philly Joe Jones and Bill Evans; how he played with Tony Williams and Herbie Hancock; how he played with Marcus and Vince Wilburn; how he played with Darryl Jones and Ricky Wellman, was the same Miles – he just wore different clothes.

If you listen to ‘U ‘n’ l’ [from the album Star People] and the swing on that track – it’s Miles like he was doing on ‘Milestones.’ He managed to be Miles Davis through all of the twentieth and into the twenty-first century. He’s the only person that I know of that will ever be able to say that they played with Charlie Parker and Prince – that says it all. Being such a visionary and surrounding himself with people that could help support his vision has always been a real standout thing for Miles Davis. People misconstrue what he said, ‘I don’t wanna look back; I don’t wanna do anything I did in the past,’ and I think that’s because the musician that made the music with Charlie Parker, his first great quintet, and the second great quintet; they were stellar musicians that were his cast – inspired him and he inspired them and it made absolutely legendary music. You have got to think about all the people that played with Miles; they had their own bands and did extremely well to create this arc of jazz music. When it started to change in the 70s, the arc had changed. In the 80s and 90s, things around the arc changed.

It was still Miles Davis and it will always be Miles Davis. All of Miles’ music is great. Marcus did a great job in looking at the landscape of what was happening to create the music that he did. I was asked to do the same thing today with ‘Hail To The Real Chief’ [the track is on the Birth of the Cool film soundtrack album] I got The Jamaica Boys to play with Miles Davis. What they [the producers] asked me to do was to listen to some of Miles’ stems from the 80s [stereo recordings sourced from a mix of individual tracks]. I had written a piece of music in 1999 that had a ridiculous groove and I used it some stems of Miles’ and got Marcus, John Scofield, Bernard Wright and Vince Wilburn Jr to play on it. I could take Miles from any era that he played and juxtapose it with the music of the time and it would fit. You can’t do that with many artists.

Lenny White: image courtesy Lenny White

TLM: When you think of Miles, what are your biggest memories, and what did you learn most from being with him?

LW: Miles was a sage. He was a person that was extremely sensitive and he created this thing because of how sensitive he was. When people see Miles and go, ‘He’s like agghhh!’ and they listen to ‘Summertime’ and they think, ‘how could a guy play with that much soul and be so gruff?’ He was always great with me – he was always teaching. He asked me to come down to a Village [Vanguard] date, because he wanted me to listen to the music, as I was about to go on the road with him. Between sets we’d I’d listen to [pianist] Les McCann’s group and he’d say, ‘See that? Listen to that. No, that’s wrong’ – he was a teacher. I have only great memories. I can equate all the great feeling I got by listening to Miles Davis play and going to his house and listening to music with him.

When he came back after not playing for all those years and he played at the Avery Fisher Hall [July 5 1981], I bought two tickets for my wife and I. He was fantastic. I went backstage and said, ‘Man, that was absolutely amazing,’ and he said, ‘How do you like my bass player?’ [Marcus Miller] and I said, ‘He played with me before he played with you!’ Then he said, ‘You played with me!’ Those are the things that do remember and they will always be with me.

TLM: We’ve obviously talked a lot about Miles, but I have to ask you about playing with Jaco Pastorius. How did you get the gig and did you know anything about him before you got it?

LW: What happened was that [Columbia Records producer] Bobby Colomby – who I knew from Blood, Sweat and Tears – had discovered Jaco and he called me up and said, ‘Hey listen man, I got this great bass player and he wants you to do his album – are you interested in doing it? He’s using Herbie [Hancock] and Hubert Laws.’ I said, ‘sure’ and we went to the studio in New York and met him for the first time. We went into the studio and started recording. In between takes, we’d go outside and play basketball. I thought it was great what we were doing – it was cool, but I never thought it was going to be the ground-breaking album that it was.

Jaco was a nova [a bright star] in terms of playing the bass, and while I was extremely impressed with what he did, I had played with Ron Carter and Stanley Clarke! Jaco had a new way of playing that was different from them. I thought it was great but never knew it was going to blow up to be so big.

TLM: What was Jaco like in the studio in terms of rehearsing – did he give much direction, especially as he was also a drummer himself?

LW: He knew what he wanted. Anytime you get an artist that knows what they want and they have included you in their quest to get that on a recording, you listen to what it is they are saying. He gave very clear instructions about what he wanted and you did the best that we could to get that.

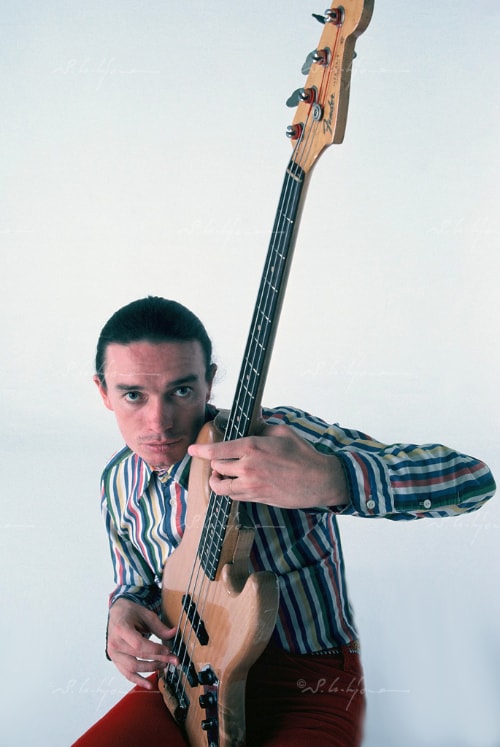

Jaco Pastorius © Shigeru Uchiyama

There was one tune that he just got Don Alias and I play in 6/4 [the tune is called ‘6/4 Jam.’ Released as a bonus cut on the special release of the Jaco Pastorius album] and it was absolutely killing – it was so great. To be able to let us do that – his ego was right on point. They didn’t overdub anything – they just let us play. For me, it was an attempt to show that I had an understanding of African roots from the standpoint of how triplets fall. Because if you listen to it, there’s a groove that happens and we play on both sides of the beat in doing that. Don and I had conversations about that and I am so grateful that they let that come out, because that gives another perspective on rhythm and how that falls.

TLM: The contrast between your drumming on ‘6/4 Jam’ and ‘Continuum’ couldn’t be greater. On the latter, your playing is so delicate – were you using brushes?

LW: No. After that record came out I was playing at the Brecker Brothers’ club, Seventh Avenue South in New York. There was Marcus Miller, Bernard Wright, Kenny Garrett and me. There was a staircase at the backend, and as we’re playing, I see this bass coming out of the stairwell, and it was Jaco, walking up the stairs, balancing the bass on his hand. Everyone goes: ‘Oh Jaco!’. So he and Marcus played ‘Continuum.’ It was double tracked on the album and they played it exactly how it sounded on the record – it was a remarkable night.

TLM: What are your memories of Jaco?

LW: Jaco went through a few different stages and I saw him in all of them. I refuse to talk about his manic stages, because there is no purpose. My involvement with him was really great – you can hear it on the recordings. He loved his family and they were great. There was a really positive rivalry between Weather Report and Return to Forever that produced great music. I remember him being a consummate person, a great guy and a family man – that’s what I take.

TLM: I’d like to focus on your incredible career, starting with your debut solo album Venusian Summer, released in 1975. What is interesting is how you went from being a session musician and a band member (with Return to Forever) to being a composer, arranger and producer. How did you make the leap?

LW: I had recorded with Miles Davis – I started with the master. The music was on an upward trajectory and I wanted to continue that trajectory. I had worked with great conceptualists like Chick Corea, Wayne Shorter, Joe Zawinul, Herbie Hancock. I had a really good viewing of the different kinds of musics that I was playing. There was the energy of rock and roll; the sophistication of jazz and my respect for orchestral music.

So when I got the opportunity to do my own project, I included all the different things that were influencing me at the time. With Venusian Summer, I had been listening to Jimi Hendrix, Sly [Stone] and classical music too. I had got involved with Patrick Gleeson, who was really one of the visionary synthesiser realists. It was really great for me because I wanted to use an orchestra and couldn’t afford one. But what we did with Patrick – and this was before polyphonic synthesisers – was we crafted a 100-piece string orchestra by playing one track at a time. It took a while to create! ‘Rainbow Delta’ was Patrick’s piece and these were all synthesiser realisations of real instruments. At the time, it was far reaching. There were others in this field, like Tomita, a Japanese synthesiser player and [American] Wendy Carlos, but it was kind of cutting edge to do this stuff and bring it into not just to an electronic environment. Patrick had done it with Herbie and [the 1972 album] Crossings. It was kind of cool to do that. It’s interesting, because a couple of years after the album was released, I was watching [news programme] 60 Minutes and they had a segment on space colonies. I’m listening and thinking, ‘This music sounds familiar – and they had used the beginning of ‘Venusian Summer’!”

Patrick Gleeson: photo courtesy of Patrick Gleeson

TLM: You had an impressive line-up of musicians.

LW: I used a great bass player, Doug Rauch, who played his butt off on the record. I used [keyboardist] Larry Young, who played with Tony Williams’ Lifetime – he was on Bitches Brew too. I used [guitarists] Al Di Meola and Larry Coryell. It was interesting because Larry was kind of Al’s mentor, in terms of the electric guitar, but they had never played together on a record. I used [guitarist] Ray Gomez. It was one of Ray’s first recordings and before he played on Stanley Clarke’s School Days. And I used David Sancious. He played synth and later became a big star, playing with Springsteen and Peter Gabriel – and he played on School Days too. Stanley was always stealing my guys! [laughs] I’m a big science fiction guy and ‘Mating Game’ was my homage to Star Trek, when [Mr] Spock was talking about it. ‘Chicken-Fried Steak’ is the rawest funk!

TLM: The first part of ‘Venusian Summer Suite’ is all keyboards, and you played piano and synths. How did you develop your keyboard skills?

LW: I just used my ears, and I go to the keyboard, put my hands down to realise what I’m trying to visualise. I don’t have any skills with that – it’s just me physically playing the keyboard and hearing the music that I want to hear.

TLM: On the track are three other keyboardists [Dr Patrick Gleeson, J. Peter Robinson and Tom Harrell]. Where you intimidated to be playing along with them?

LW: Of course, but what you have to be able to do in life is fail at something. You have to fail to learn something from the failure that you have, so that you don’t let the fear of failing overcome your ability to try to do something. I realised this music and then try to do it, and when I fall short, somebody can least hear my intensions and say, ‘Okay, this is how you do it.’ I’ve been sustained by some of the greatest composers of the twentieth century and something’s rubbed off and you have enough gumption to try something – that’s what you do.

TLM: How do you work as a producer? Some producers have a definite idea and a vision, and they go into the studio, and that’s what you see at the end. Others have some ideas but the studio in some way becomes a laboratory, where the players are encouraged to improvise or throw in ideas.

LW: I’m a huge movie fan and how I produce is how a director directs. The script is the music and the musicians are the actors, and I’m the director. I do have an idea about certain things when I go in to produce records. Law is based on precedent and so is music to some extent. I’ve listened to music all my life, so I can listen to Frank Sinatra singing, ‘It Was A Very Good Year’, and know that the string arrangement was by Gordon Jenkins. I recorded this tune with Diane Reeves on one of my albums [1998 Edge], so I kind of adopted it in my way. There’s so much music that I can reference. Producers reference other records but they take it out of the perspective from when they first heard and apply it to their perspective of what they trying to do musically at this point. There are a bunch of producers whose work I definitely respect, and if I’m doing a production I might think, ‘You know what, I can reference that record. And do it here’. That’s how I work.

TLM: What makes a good session musician for you – how do you select the musicians for a particular track or song?

LW: I kind of got that from Miles Davis. Miles was really adept at choosing musicians that he could ask to do something and not tell them exactly what to do. They had a vision and he thought that they could bring something to the project that he might not have thought about – Herbie Hancock, Tony Williams, Ron Carter, Wayne Shorter – they were all visionary musicians and they might not do things that normal musicians would do. You can get someone who is very adept at reading charts but might not be the kind of musician you need to inspire something that hasn’t been heard or done before. I kind of use that perspective because a lot of the music that I might try to do is not bound by certain guidelines.

Lenny White: Big City

TLM: On your album Big City is a beautiful piece of music, ‘Enchanted Pool Suite’ which features Jan Hammer and Jerry Goodman from Mahavishnu Orchesta. How did that piece develop?

LW: Mahavishnu, Return to Forever, Weather Report, Tony Williams’ Lifetime and Head Hunters – somebody from each of those bands was represented on Bitches Brew, so there was music before Bitches Brew, and music after Bitches Brew. There was a very healthy competition between those bands and all of us got to be friends. So I didn’t hesitate to call Jan and Jerry and it was absolutely great to do that. The ‘Enchanted Pool Suite’ was about sirens. I have always wanted to visualise things with my music – what I like to do is to make audio movies. I got this from listening to progressive rock – King Crimson, Yes; I was inspired by that. So, I wrote this piece that had movements and the movements were the orchestra. I took my project to Michael Gibbs, who’s a fantastic composer, arranger and conductor, and I’ll never forget when I asked Michael to be a part of the project. I was so apologetic and I said, ‘Michael, I’m not a very schooled musician, but this is what I’m hearing,’ and I gave him my music, which had been written on a synth, and he said, ‘If you had gone to school, you would not have made music like this and I’m glad that you didn’t go.’ He was really cool – he loved it, and he put together an orchestra to play it. I thanked him. Miroslav Vitous played acoustic bass and said that it was one of the hardest bass parts he’d ever played – I was just thinking about the music; I never thought about the dexterity you might need to play a bass line like that. Gary King was the electric bass player.

We would take musicians out of the context of what they would normally do and they started to do different things. There’s some good stuff on that record, like a guitar duet between Neal Schon and Ray Gomez [on ‘And We Meet Again.’] Herbie Hancock was on the record and a great singer Linda Tillery, who sang ‘Sweet Dreamer.’ It was a very diverse record and I like it a lot.

TLM: Your follow-up album in 1978 was The Adventures of The Astral Pirates. I take it you were inspired by Star Wars? It featured the keyboardist/vocalist Don Blackman, who was a very interesting character and had worked with Parliament / Funkadelic.

LW: Yes it was. Donald, Bernard Wright, Marcus Miller and Omar Hakim were all from Jamaica, Queens – they were just guys from the neighbourhood. I wrote this story and I wanted to do another audio-movie – I wanted music that went with the story. Record executive Don Mizell signed me – I was the first black artist signed to Elektra Records. We put together this story and this was the soundtrack to the story. I did that record with [composer, producer and musician] Al Kooper. Of all the records that I’ve done, I don’t know if I really like it. I didn’t like the way I played; I didn’t like the sound after I had listened to it. But the fact that a lot of people like it, I’m fine with that. As an artist, you do things and put it out and hope that people like what it is you do, so I’m very appreciative of people really liking it.

TLM: The track ‘Universal Love’ could have [the late] Maurice White of Earth, Wind & Fire singing on it.

LW: Maurice was a big influence. He, [Miles’ third wife, the late] Cicely Tyson and I were all born on December 19.

Twennynine: Best of Friends

TLM: Moving onto Twennynine. I assume it was called that because it was your age at the time?

LW: Exactly.

TLM: With the band, you seemed to have moved from jazz-rock towards R&B and funk.

LW: This is no reflection on you George, but people tend to lump certain kinds of music and put names on them – they kind of marginalise music by putting them in categories. Funk – no one that uses that word today understands what that is. The fact that anytime somebody puts a backbeat and does the thumping with the bass, they call that funk – that’s not the case. I’m old enough to know where musical genres come from and to be able to identify and authentically play that music. We did a performance on American Bandstand and [host] Dick Clark asked what we called the music and I said, ‘Progressive pop music with an R&B base.’ That’s too much for DJs to say, so they said, ‘That’s just R&B,’ but R&B wasn’t that sophisticated – it didn’t use those kinds of chords or some of those rhythms. If an R&B person heard it, they’d say it was jazz. The best thing an artist can do if they are going to fuse different genres is call it what you know what it is, and so, that’s what I was doing.

TLM: I shall wash my mouth out Lenny! Going onto the band, it had terrific vocalists. I’m talking about Lynn Davis, who had worked with George Duke; Jocelyn Smith, who would sing with the Berlin Philharmonic, and Tanya Willoughby, who would work with the band Change. Where did you find all these marvellous singers?

LW: They were from the hood! I met Tanya and liked the sound of her voice – she blended well with the concept of what I wanted to do. As a leader, you want to find people that can bring something to the concept and Tanya also wrote great lyrics. My mum was a teacher’s aide at a school in Queens and she said, ‘You have got to hear this girl sing’ – that was Jocelyn. I met Lyn Davis in LA – she had worked with a few people. [Earth, Wind & Fire keyboardist] Larry Dunn turned me onto her.

TLM: How did you get to work with Larry Dunn, who co-produced with you Twennynine’s first two albums?

TLM: I had known him since 1971. I played in a band called Azteca, which was signed to Columbia Records. It was like a cross between Santana and Blood, Sweat and Tears, and had a Latin rhythm section; four singers, four horns and three keyboard players – it was a huge band. There was a great trumpet player, Tom Harrell, Neal Schon on guitar and [percussionists] Coke and Pete Escovedo. Clive Davis, then head of Columbia Records, had a convention in London at the Grosvenor House Hotel. Clive had just signed Earth, Wind & Fire from Warner Bros, and I met all the guys at the convention. Earth, Wind & Fire were kind of the model for my Twennynine band, because it showed that R&B could be more than just R&B. Not that R&B didn’t have a message, but Earth, Wind & Fire had a universal message. It was a black message and it was a lot deeper than, ‘Oh baby, I love you.’ It was a good guide to us. So, I called Larry to come and work with me, and Twennynine definitely had an Earth, Wind & Fire vibe. I wish the band had done better. We had a big hit with a song that Don Blackman had written, ‘Peanut Butter’ and I got to do Prince’s first US tour. Rick James was headlining, then came Prince, and then my band. We toured across the US in 1980.

Azteca: Lenny is in the middle of the back row

TLM: What was Prince like in those days?

LW: He was cool and I got to know him. He saw us on American Bandstand. We were the opening band for the tour, so when we were playing, people were getting their popcorn rather than listening to the music! The more people on stage than in the audience! But Prince’s band was standing onstage watching us every night.

TLM: Could you tell even back then that this man had talent and was going to be amazing?

LW: Without a doubt. Sexy dancing and all of that stuff. His music was great and they would open up vamps for the guys to play. His music was different.

TLM: We have talked briefly about The Jamaica Boys, but I’d like to know more about how you got together.

LW: Marcus [Miller] and Bernard [Wright] were in one of my early bands. Marcus said, ‘Let’s form a band from the hood and that’s what you got. We had Chaka Khan’s brother Mark Stevens and we started a band. Marcus’s manager at the time, Patrick Rains got us a deal with Warner. We did a first album, and we got an opportunity to do a second album [J-Boys]. Marcus and I had done [film director] Reggie Hudlin’s first movie, House Party [released in 1990] and we had a tune in that movie, ‘Shake It Up!’, with a different singer Dinky Bingham. It was great to do that band and we made some great music.

TLM: ‘Serious’ from the band’s first album is one of my favourites – it’s got a great groove.

LW: What was good about that, and another track we did, ‘Romeo’, was that there was no click track – it was just Bernard and I going in and playing, with everyone else dubbed on top.

TLM: I love the live performance of ‘Shake It Up!’, Marcus Miller is one helluva of a dancer – is there anything he can’t do?!

LW: We had a great time on Arsenio Hall too – that was fun.

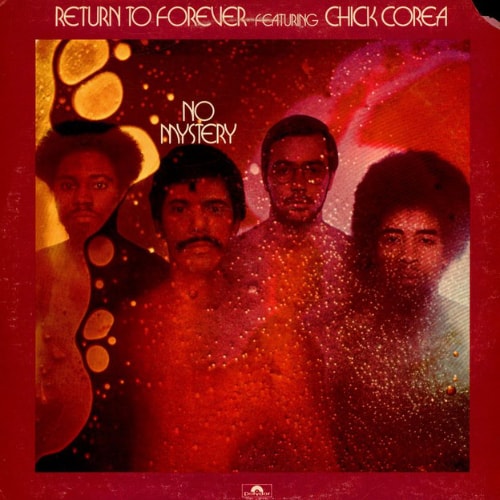

Return To Forever: No Mystery

TLM: Jumping about chronologically, just before you joined Return to Forever in 1973, you almost joined the band Journey [the band went onto great success, racking up 25 gold and platinum albums]. In fact, you were the first person to play with the guys while they were forming the band.

LW: That’s right. What happened was that I was in San Francisco with Azteca – all the guys were from the Bay Area, and I was the only one not from there, so I would commute from New York to San Francisco and stay out there for six weeks. While I was out there, Chick Corea called me from Japan because the Return to Forever band with [percussionist] Airto [Morera] and [singer] Flora [Purim] and [woodwind player] Joe Farrell, Stanley [Clarke] and Chick was breaking up. Stanley and Chick were coming to San Francisco to play at the Keystone Korner [jazz club] and they asked me to play.

We did the gig at the Keystone and it was absolutely amazing. On the last night, Chick had two guitarists sit in from the Bay Area, Barry Finnerty and Bill Connors. At the end of the night, Chick said to me, ‘I want to start an electric Return to Forever, would you do it?’ I said, ‘Chick, I’m with this band Azteca and I think I’m going to stay out here with the band.’ They went back to New York and asked Steve Gadd if he would be part of the band. Meanwhile, I was still out in San Francisco and a manager called me and said, ‘Listen, Neal Schon and [bassist] Ross Valory would like to jam with you – do you have time?’ We went to SIR [Studio Instrument Rentals whose facilities include a rehearsal studio] and we jammed. [keyboardist and vocalist] Gregg Rolie – who I knew from Santana – said, ‘Listen man, the guys really love the way you play. They’re starting a band and would like you to play in it.’ By this time, Chick had called me again, because Steve Gadd didn’t want to go on the road. He asked me again and this time I said yes. So I went back to do Return for Forever and the band that I was supposed to join became Journey.

TLM: Return to Forever was Chick Corea on keyboards, Bill Connors – who was later replaced by Al Di Meola – on guitar, Stanley Clarke on bass, and you on drums. What were the dynamics like in the band?

LW: I’ll tell you a true story. Years after Return to Forever had broken up [the band ended in 1978] and we were not talking. I was in LA at Catalina’s [jazz club] with my Present Tense band and Chick called me. I went to his house and we had a conversation. He said, ‘You know, Return to Forever was my band. I started it and what happened was that it got big – I couldn’t handle the fact that it had gotten away from me. It started out as ‘Chick Corea and Return to Forever’, then it became ‘Return to Forever featuring Chick Corea’ and finally, ’Return to Forever’.

TLM: When you look back at Return to Forever in the 70s, what are your thoughts on the music you produced?

LW: I thought it was ground breaking. Here’s the testimony. When you go back and look at those bands – Return to Forever; Mahavishnu Orchestra; Weather Report and Head Hunters, have you seen bands do cover tunes of any Return to Forever tunes? The real thing about Return to Forever is that, of all of those bands, Return to Forever, had a real jazz rhythm section – it was more of a jazz band playing their version of rock. Weather Report didn’t play rock and roll, because there was no guitar, so I think that’s the difference. The phrasing was straight out of a jazz rhythm section. Chick’s compositions were the inspiration for all of our compositions to do a certain thing. The difference with Return to Forever is that, depending on the energy that we wanted created, we took from different kinds of musics. If you think about No Mystery [their 1975 album], there’s a certain kind of energy to the music that is classical, but it’s not classical music for classical music’s sake. It’s a certain kind of energy that classical music gives to a composition. The same thing with [the 1976 album] Romantic Warrior. That’s why I don’t think a lot of bands did cover versions, because there was much more of a commitment to straddle these musical energies and play them with conviction – you have to work at it to do that. Mahavishnu Orchestra had a rock and roll energy level. That’s just my take on it and I’m not trying to disparage anyone – that’s just telling you how I saw it.

TLM: Can a band have too much talent – is that why Return to Forever broke up at the end?

LW: You could say that. Whatever I say is just from my perspective. I’m not trying to say something that would fault somebody. Every artist has their trajectory they will try to adhere it. What they want to do is they should try to do and they should not let anybody shape that, because that’s destructive. I don’t fault anybody – that’s not the issue at all. I want everybody to understand that the reason why I started to play music was not to make money – never was. But when I started to make money, it became an issue!

TLM: Return to Forever reformed in 2008 with you, Chick Corea, Stanley Clarke and Al Di Meola. In 2009, you, Chick Corea and Stanley Clarke toured and released a live album, Forever. In 2011, Return to Forever toured again, although with Al Di Meola replaced on guitar by Frank Gambale, and Jean-Luc Ponty joining the line-up on electric violin. Can you tell us about this period?

LW: That project came about because of the demand. We got a reach from the audience, from the fans – they wanted to see that [band]; they missed it. We had left a mark and our fans had gotten older. They had kids and wanted to bring their kids to experience what they had experienced when we came on the scene. It was great because there was a lineage. When you discover some music; when you discover some art or a movie, you want to give somebody the same opportunity to be inspired in the way you were. It was fantastic; it was great. I would do it again but I wouldn’t want to play that same music again, because everyone has grown and I would love to see what we can do now. That would be an interesting scenario. [Sadly, this interview took place shortly before Chick Corea’s, sudden, unexpected death in February 2021]

TLM: You were very much part of the golden age of jazz-rock fusion. What caused its eventual demise?

LW: There’s a possibility that there’s a documentary going to be made about that. There are a lot of different theories and I wouldn’t go out on a limb and say, ‘this is the reason why,’ because I think there are a lot of different reasons why things happen. But that music was extremely strong. One of the things that will stay for me for the rest of my life is that Return to Forever released Romantic Warrior, and in Central Park there’s a skating rink which held concerts during the summer that held 7000 people. When Return to Forever played there, they broke down the fences and there were 12,000 people for that concert. We did not have a lead singer; we did not have a radio hit and yet 12,000 people came to see an instrumental band play music that was not played on the radio – it was very powerful music. I’m not sure if the powers that be infiltrated the bands and said, ‘this should be your band’ or ‘you should have your own band,’ and got inside to disperse that energy – I don’t know. At the time, I was trying to be the best that I could be. That was a meritocracy. That movement was really strong because everybody within it was on-point. It had to be, to be able to have that thrust. There was an arc with that music and that direction and it was very powerful.

TLM: Time is getting on and there are countless other projects I’d love to talk to you about, but one I must ask you about was that terrific trio you formed with Larry Coryell on guitar and Victor Bailey on bass – how did that happen?

LW: I had played an awful lot with Victor – Victor is on almost all my records. The three of us had gotten an offer to do a record for an audiophile company Chesky. We did a couple of records and there was a single microphone. There was no mixing – it was just like the time when you played and that’s what it was. We had a great time playing together.

Victor Bailey

TLM: You’ve played with a lot of people, who are no longer with us, like Larry [who died in 2017] and Victor [he died in 2016]. Victor’s death was particularly hard, because he was so young [56].

LW: Very much so, and because I saw Victor go through a debilitating disease [he had a genetic muscle-wasting disorder]. He was a great musician. I was with Victor up to his last days – it was heart-breaking to see a spirit like that silenced. He was a great spirit and that made him a fantastic musician. I had done a record that he wanted released and I started working to finish it, but I ran out of money to be able to do that. I still have that music and hope one day to put it out, because he was a special spirit.

TLM: During the release of your 2010 album Anomaly, you said some interesting things around that period: ‘Let’s restart a revolution so we can take back the music and stop the fluff’; ‘this is not a boy-band; it’s a man-band’; ‘let’s put the rock back into jazz-rock’; ‘I want to play music like it used to be played.’ You sound like you weren’t too happy with the music business.

LW: I’m still not happy because of what the original intention was. As I said earlier, I didn’t get into the music business to make money; I got into it because it was a form of expression – I got to express myself in bands and with artists that were ground-breaking. I wanted to perpetuate that feeling and that energy. I wanted to continue to do that on my own. Then there’s the fact that you want to make music that is inspirational, but in doing that, someone gives you an opportunity, and you have adhere to a certain quota to be able to continue that. So you have to make music that generates money for whatever company gives you the opportunity.

What happens is that you tend to somewhat compromise your original intention, because you have to abide by the status quo. Maybe at the beginning you just compromise enough, but as it goes on, your obligation comes back on you, and you may have to compromise a bit more. That attitude is counter-productive to art, because art creates an arc, and so now if you’re starting to manufacture your art, then maybe the arc turns and goes down – I believe that’s where we are. I believe that artists are not necessarily trying to inspire and create new things – they’re trying to be popular because music has become a commodity. In order to have that opportunity to create and put it in the market place, you have to abide by certain things. What has changed is that you do not have to do that. You can make your own music for yourself and put it out yourself. It’s just might not get felt the way it should – that’s the issue. You can get heard, but I don’t just want to get heard; I want to get felt, and that’s a big difference.

TLM: You won two Grammy’s in consecutive years [2010 best contemporary jazz album, for The Stanley Clarke Band, and in 2011, best jazz instrumental album, Forever, with Chick Corea and Stanley Clarke] Did that not help your career?

LW: No! No! it’s a very interesting thing. I have four Grammys [the other two are Return to Forever’s No Mystery won best jazz performance by a group in 1975, and Forever also won a Latin Grammy]. If I was an actor, the equivalent would be an Oscar. If I had four Oscars I could name my price and could do work that I would feel good about. It’s not the case with music because it’s been devalued since Napster – people don’t want to pay for music anymore. Music had a value; people paid money to listen to it and to go and see and experience music – they don’t want to do that anymore because there has been the opportunity to get it for free. ‘Why pay for something you can get for free?’ We don’t say that about water.

When the music business was losing a lot of money because people were not buying albums anymore, they got something called streaming. Now, the music business is making a whole bunch of money but not the artist. They have found a way to jack the artists and make money. You get a million streams and make $300. What has happened is that some artists have gotten pretty despondent because of these situations: ‘why am I working and making the time to make this music? No one’s going to hear it. If it’s streamed, I’m not going to make any money from it.’ Something has to change.

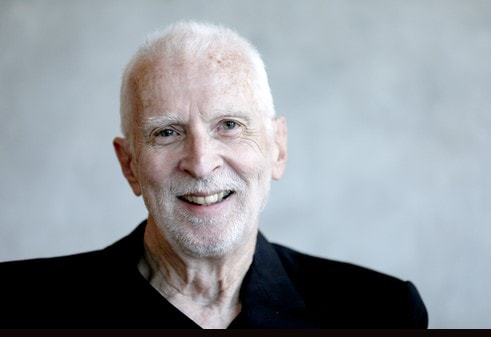

Lenny White: image courtesy Lenny White

TLM: Nevertheless, you’ve had a remarkable career stretching over 50 years and played with so many amazing musicians. You have been involved in the creation of so much fantastic music, which people are still listening to decades on, and will continue to do so. To keep going this long is such a great achievement. It is a challenging time for the creative industry, but I know you still have many more things you want to say, musically. You must feel some satisfaction and pride?

LW: Yes, I actually do, but it’s all relative. I think if more people were educated about all these different musical stops on this journey, I think recognition would be informed. Basically, I’m not asking, because that would be begging – I don’t need that. I know who I am, I know what I have done; I just want the opportunity to talk about it. The more opportunities I can get to create art and put it in the market place [the better], because I honestly do feel that I can create some art that can change these conditions. I think I can make a positive statement in these conditions. Because I’ve done it before; I’ve been involved in bands where the energy of what we were creating was extremely positive, uplifting and it had an arc. So I spend my waking hours trying to recreate that positivity – that’s all I ask.

Many thanks to Lenny for spending so much time talking with us.

Thanks also to Dr Patrick Gleeson – www.patrickgleesonmusic.com/.