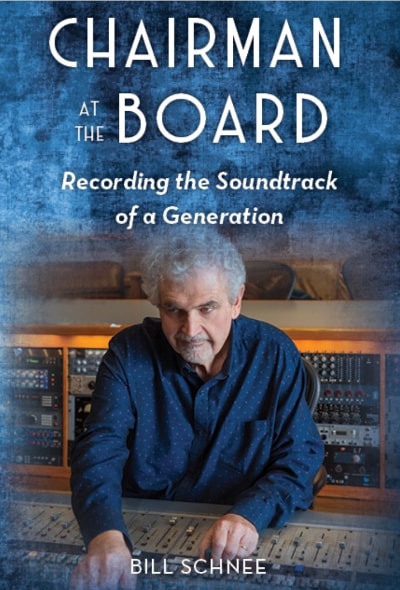

Producer, engineer and mixing specialist Bill Schnee is quite simply, one of the most talented audio engineers of his generation. Bill, who was born in Phoenix, Arizona in 1947, has won numerous awards including, two Grammys and an Emmy, and has worked on more than 125 Gold and Platinum records. He also built his own recording studio, Bill Schnee Studio, in Hollywood. The many artists associated with Bill include, Boz Scaggs, Steely Dan, Marvin Gaye, George Benson, Larry Carlton, Whitney Houston, Barry Manilow, Barbara Streisand, Carly Simon, Marcus Miller – and Miles. Bill mixed three tracks on Tutu, the multi-channel version of Tutu and the entire Amandla album. In this interview, Bill talks about his long and distinguished career; his approach to audio engineering, and what it was like working on Miles’s albums.

Bill Schnee: ‘I’d rather listen to mediocre-sounding great music than excellent-sounding mediocre music’

The Last Miles: You have had incredible success as a recording engineer, mixing engineer and producer. Can you define these roles in your own words?

Bill Schnee: The basic differences between the three jobs are this. The producer is the person that’s responsible for coming up with the record: where once was nothing; there is now a record. His job is to take the money that the record company gives him and use the budget to come up with a record. Sometimes, it can be little more than just standing there and keeping track of takes and telling them which one is best. Other times, it goes all the way to helping write the songs. There are all different kinds of producers and there’s no one that is better than the others. They used to call it a marriage between an artist and producer, and I think that’s a great analogy.

All that matters is that a certain producer works well with a certain artist. For instance, P-Daddy can write a song; arrange the song, produce the song and record the artist – they just come in and sing it. And if he doesn’t like what they do; he’ll sing it himself. That’s one extreme end of the spectrum of producing, and at the other end are what I call the chemists. They don’t have much to do with the music itself, but rather pick all the elements that make the record (studio, engineer, arranger, etcetera), and then stir them up to make it happen. So that’s the basic gamut of the type of producers out there.

The engineer is the guy that’s responsible for the aural landscape of the record. He’s the one that will do the recording – the mic’ing and so on to capture the performances. After all the tracks have been assembled and recorded, the mixing engineer is the one that will go in the studio and assemble the mix. He does this by changing tones, adding depth, reverb, compression, and different effects to hopefully make a good aesthetic out of each song and ultimately the album.

TLM: Some producers come from a musical background; others from a technical. You come out of both, so presumably this is an advantage?

Bill: Yes, I think it is. I think honestly that the musical background is much more helpful than the technical. There are many more good producers that don’t know much about technology than technically-orientated ones – the producer/engineer; as opposed to the engineer/producer. Even then, there are certain bands where an engineer/producer is perhaps all they need; somebody to help them along and they really co-produce the record. Again, it’s a matter of matching up the two together.

TLM: Of the three roles, which is your favourite?

Bill: Producing is my favourite; mixing is second, and engineering last. I love engineering, but I don’t love engineering for other people when they’re not together: when the producer doesn’t really know what he’s doing or a band doesn’t know what they’re doing. That can be very frustrating.

TLM: Are you able to listen to music for pleasure or are you too busy thinking about the mix or the production or whatever?

Bill: It depends. I really try not to listen as a professional and really enjoy the music, but I’d be lying if I said my profession doesn’t creep in. My wife loves music but knows little about the business and certainly nothing about the technology. She says that in her mind, music has been ruined for me, because I can’t listen without analysing something. That said, the further I get away from things that have been done, it gets a little easier to listen. So if I’m listening to [the 1960 Miles Davis/Gil Evans album] Sketches of Spain, then I can just completely relax and listen. But I try to keep up with modern music, because that’s becoming my world, so I’m constantly analysing.

In fact, I’m half way producing an album with a very creative female artist, and although I have a huge collection of vintage microphones, I’ve only used one mic on the project, and that was to record her voice – everything else is in the box [computer]. It’s samples and beats, because that’s so much of what is going on today. I didn’t know what I was going to think about working this way, but I’m working with some very talented programmers, which has helped a lot. It’s different but I’m really enjoying it.

Bill Schnee: Chairman at the Board

TLM: You’ve now chronicled your amazing career in a new book with the great title, Chairman at the Board. What motivated you to write it?

Bill: I love telling stories and have had a wonderfully blessed career. People were always saying, ‘Why don’t you write a book?’ but I thought it would be too self-serving – ‘I did this and then I did that.’ It all changed when the producer of a Brazilian artist took me to dinner after a session and said, ‘You should write a book,’ and I said, ‘I’ve heard all that before.’ Then he said, ‘Seriously, the golden era for music was the 70s into the 80s and you were there.’ Then it hit me that it wouldn’t have to be all about me. I could tell fun stories I’ve heard that had nothing to do with me. I wrote the book for anyone like me who loves music and records, but hasn’t been as fortunate as I have and gone behind the curtain. In essence, I wrote it for ‘the guy next door.’ A lot of people in the business who know what I’ve done were expecting a different book – something much more technical. When I turned it in, the publisher suggested I put some educational stuff in it, so I wrote another 15,000 words. I love that the editor put this material at the end of the story chapters. This way, the person just interested in the stories can read them and ignore the rest, while those wanting more technical information can read on.

TLM: Your book is cross between a physical book and an ebook, because readers can find additional material online.

Bill: About a third of the manuscript was cut in editing, and so many stories were left out. Readers will find a key word in the book with instructions that allows the reader to access ‘the deleted scenes’ on my website.

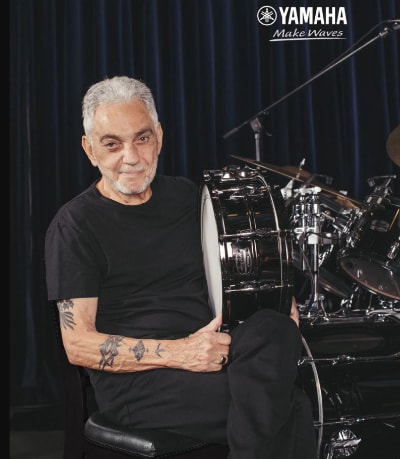

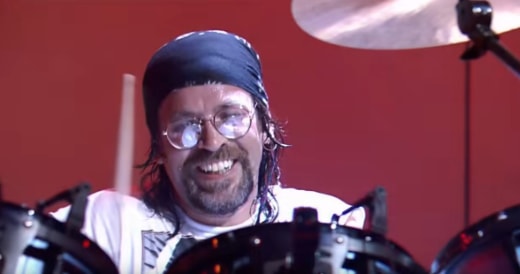

Steve Gadd © Yamaha

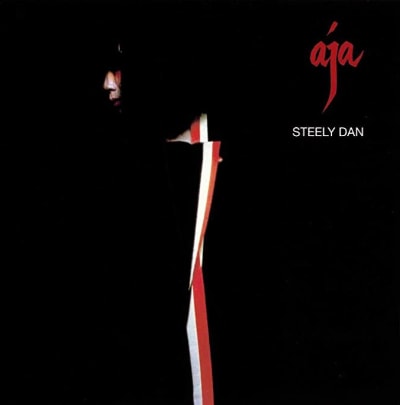

TLM: Before we talk about your work with Miles, I’m going to be self-indulgent and ask you about two of the many projects you’ve worked on. The first is Steely Dan and that amazing drum performance by Steve Gadd on the track ‘Aja’ – his soloing is jaw-dropping.’ It must have been amazing to have witnessed that happening.

Bill: [Steely Dan producer] Gary Katz called and asked if I would like to do the next Steely Dan album, and of course, I jumped at it because I was a big fan of the band. He told me, ‘By the way, there’s going to be a revolving door of drummers.’ I asked what he meant and he replied, ‘We’re going to have six, eight, maybe nine drummers, so you’ll have a new drum sound every few days.’

On the third day, in from New York came Steve Gadd. I had fallen in love with his playing on Paul Simon’s ’50 Ways To Leave Your Lover,’ so I was just thrilled. After the first day of recording Steve, I was so excited that I called my friend, that great record producer Richard Perry and told him I was working with Steve and that he was a monster. Richard said, ‘Can I have a session with him?’ I said, ‘He’s leaving town the day after tomorrow when we’re done, but we don’t start until 2 o’clock, so let me ask Gary Katz if you can have a morning session.’ Gary said okay, but he knew Richard’s ways and that it always took a lot of time to get a take, sometimes hours and hours. So Gary said, ‘You have to get him out. If I don’t start at 2pm, the boys [Steely Dan’s Walter Becker and Donald Fagen] are going to kill me.’

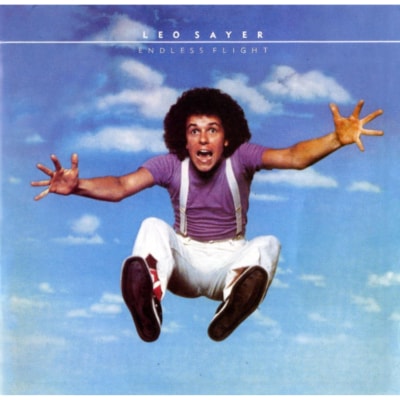

So, Richard popped in the next morning with [British pop singer] Leo Sayer and we cut, ‘You Make Me Feel Like Dancing.’ Steve played the drag snare he’d used on ’50 Ways’ but with a different groove. We had the track done in a couple of hours, which was possibly a world record for Richard! Richard asked if we could do another song and I reminded him that we had to be out by 2pm. So, we cut a second track, ‘How Much Love.’ ‘You Make Me Feel Like Dancing’ was the first hit [of the album Endless Flight] and ‘How Much Love’ was the third single.

Leo Sayer’s Endless Flight album included ‘You Make Me Feel Like Dancing’

So we had cut two of the big singles for Leo in the morning and then went on to record ‘Aja’ in the afternoon – to say it was a full day for Mr Gadd would be a mild understatement… I can tell you this about that solo. A couple of months ago, I was with [keyboardist/producer] Michael Omartian, who played piano on the track, and he reminded me that it was the hardest track to get – the chart was huge. [Becker and Fagen] came into the studio every day with a piano/bass demo, and sometimes a guide vocal. They had given them to the great guitarist Larry Carlton, who wrote the chord charts based off of the demos. With ‘Aja,’ we had a lot more working out to do. The chart was four pages and we spent lots of time rehearsing it, not on making takes. We did it in two takes, period! Now, people want to know if the take on the record – is the first one or the second? If you go online, you’ll find the basic track [the recording before various overdubs are added] for one of the takes and it’s the one with the stick clicks [Gadd’s drumsticks click together during the first solo part], but as for which take it is, I don’t remember.

TLM: The tune ends with a second stunning solo by Steve Gadd and one wishes it would go on forever. Do you know if it lasted much longer than beyond the fade-out?

Bill: I don’t remember, but I think that was about it.

Steely Dan: Aja

TLM: From what I’ve read, you have fond memories of the Aja sessions.

Bill: The great thing about those sessions is that they were not like the previous [Steely Dan] albums or the next [Goucho]. From what I can tell, that’s the only album that was done with great studio musicians and was very organised. We started at two and didn’t go very late – everything about it was extremely well laid out. But then, they [Becker and Fagen] went off and took the microscope out and tried this and tried that. The great thing is, they didn’t smother anything. They did a very good job of not layering too many things and smothering the greatness in the live tracks. In every case it was magic; everyday, I’d get in my car and pop in a cassette of what we had done and just marvel at it. I couldn’t believe what I was listening to – it was a little poppy; it was a little jazzy, but it was certainly not pop or jazz, and it gets bluesy once in a while. All I could think was, ‘I don’t know what it is, but it’s incredible.’

TLM: The Aja album is like a who’s who of drummers, but one name is conspicuous by its absence – the late, great Jeff Porcaro. It’s a shame he’s not on it.

Bill: It is a great shame. Jeff had played on the previous two Steely Dan albums and would play on [the following album] Goucho, so I’m not sure why he wasn’t called.

Jeff Porcaro

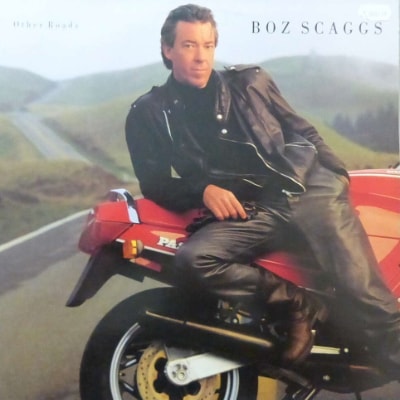

TLM: However, Jeff Porcaro did play on another album I want to talk about and that’s Boz Scagg’s Middle Man [released in 1980] which you produced.

Bill: There’s a funny Aja connection there, because guitarist Jay Graydon, who wears the great solo he played on [the Aja track] ‘Peg’ like a war wound, played a solo on the ballad ‘You Can Have Me Anytime.’ But Boz felt it was too slick and came up with the idea of using Carlos Santana. I thought, ‘Wow!’ because the song has a lot of chord changes that Carlos wasn’t used to playing through. So I made a rough mix for Carlos and sent it to him, so he could work on it before we recorded it. He had a tough time playing it and I definitely did a bit of comping [compiling a performance from various sections] to make the solo, but I really love it, especially with Marty Paich’s gorgeous string chart – I thought it was like sweet and sour. When we finished the album, I played it to [keyboardist/composer/producer] David Foster, who had worked closely with Boz on the album. He said, ‘You did a marvellous job, except for that guitar solo!’ He and Graydon are very tight and were in a band together [Airplay], so I’m sure that’s where that came from! I’m not sure Jay has forgiven me. I love it; Boz loves and it’s there for all time.

TLM: Wasn’t a musician replaced on the opening track ‘Jo-Jo’?

Bill: David Hungate was meant to play bass on the track. We were working at Cherokee Studios [in LA] and [guitarist Steve] Lukather walked in the night of the session and said, ‘David’s sick, but it’s okay – I’ve got a guy’. And in walked John Pierce, who was very young and a little green, but he killed the living daylights out of the groove with Jeff.

TLM: How did you end up co-composer of ‘You Got Some Imagination’?

Bill: Whenever I have worked with an artist, I’ve always offered ideas and I have never asked for a writer’s credit. I cut a song with a band called Pablo Cruise, ‘Love Will Find A Way’ and if there’s a song where I deserved a credit, it was that one, but I didn’t ask for it. Funnily enough, the record came out and a songwriter sued us, saying that our chorus was his verse or vice-versa. Ultimately, the case got dropped and the only people who came out of it well were the lawyers. I’ve no idea about ‘You Got Some Imagination’. There have been a couple of times – Boz being one of them – where people have said, ‘I’m going to give you a certain percentage of this,’ but there have been plenty of times when I’ve offered things and wasn’t offered anything in return, so, I don’t know what to tell you.

TLM: As much as I love Boz Scaggs’ Silk Degrees, it’s Middle Man that I invariably play the most. You must be proud of that album.

Bill: Yes, very much.

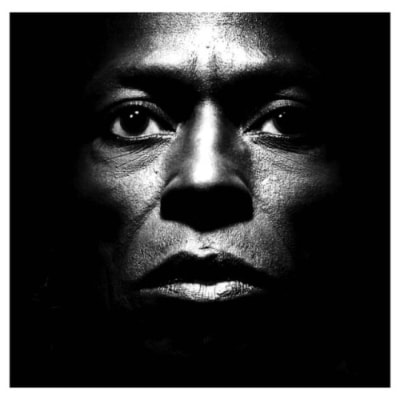

Miles Davis: Tutu

TLM: When it comes to Miles, your role on both Tutu and Amandla was mixing engineer. I’d like to start by talking about mixing generally. You once said, ‘There’s no such thing as the perfect mix,’ and that, ‘what matters is getting the feel right rather than the sound.’ Could you elaborate on this?

Bill: There’s the recorded sound of the record which is made up of all the instruments, their ranges and so on. The good job of arranging a song is having those things not step on each other: having the space for everything musically really helps. When it comes to mixing it makes things easier. There’s nothing worse than a song where people haven’t taken that into consideration and often you’ve got two guitars sitting on top of a piano in the same range. They just cloud each other and you don’t hear anything. Another masterful piece about Aja was how they didn’t mess it up with lots of overdubs. That’s really important as far as the sound goes, and then how well those instruments have been recorded, and how they blend together, and so forth.

A phenomenal sound on everything doesn’t necessarily make a phenomenal-sounding record; in fact, sometimes they can compete with each other and have a deleterious effect. So it’s a matter of making that work as you’re blending things in. So, that’s the recorded sound of the record. In engineering, people tend to think about the sound. When most people say, ‘that sounds really good’ they don’t really mean the recorded sound. They mean the music sounds good. I obviously think sound is important – I got into it for that reason. I had a band right out of high school [LA Teens] and we recorded at Capitol and United, two of the best studios to this day in Hollywood. Our second producer, Richard Podolor had a funky little studio, but when I heard the first playback, the emotional additive of what I heard out of those speakers was like nothing I had heard in those two other great studios. Yes, they had great studios and great mics, but talent is using the equipment. His [Podolor’s] equipment wasn’t any better, but he was better than those other engineers. So, it’s always been important for me to get the emotional content out of the song by what you’re doing with it. That’s what I go for.

Sound is important, but the feel is more important. It has to be on the tape – it’s hard to manufacture feel. But it’s easy to lose great feel in the mix. There is no such thing as the perfect mix as there’s more than one way to skin a cat. Back in the 80s and 90s, when money was less of an object, record companies would get two or three engineers to a mix a single and pick the best one. I was involved in some of these and it’s amazing to me that they were all good. There are plenty of records from the past that don’t sound very good but feel phenomenal. I’d rather listen to mediocre-sounding great music than excellent-sounding mediocre music.

TLM: Do you have a set process for mixing or does it depend on the project or the producer or the artist?

Bill: If I do, I don’t know it. I approach different things differently, but in terms of the actual process, I don’t know. I love to get a rough mix to see what they think it should be like, but try not to listen to the rough mix too much. Typically, I’ll get something up that I like and then listen to the rough mix. If I think there are elements of theirs that I should use, I’ll adjust my mix, if not, I’ll keep going on mine.

TLM: When it comes to creating the mix, do you have to park your ego? What happens when you come up with something that you think is great, but the artist or producer says, ‘No, no, I want something else.’? Is it like being a chef who creates a great dish only for the customer to say, ‘Not bad, but it’ll taste better with lots more salt in it?’

Bill: I like to think that to the world at large, I hope I have no ego, but my wife might say otherwise! I will say this seriously: I do try to keep my ego in check. I’ve always said that this art is very subjective – what’s right and what’s wrong is in the ear of the beholder, and the only beholder that matters is the artist or the producer. I won’t be offended if you don’t like what I have. To a fault sometimes, I will change things, and that’s why working with Richard Perry sometimes was so frustrating. He would come in and say, ‘what about a little more of this or what about a little less of that?’ The analogy I make is that if you look at the mix as forest, we shouldn’t really care about the individual trees – it should just be a beautiful lush forest. But Richard would say, ‘That pine tree should be another foot shorter and that oak belongs over to the right.’ After three, four hours of that, he’s got the trees arranged exactly the way he wants. Does it feel as good as the mix we had when he walked in? Oftentimes, no. Quite a few times I would say, ‘Richard, you’ve blown it. The trees look fine, but it doesn’t feel as good.’

Richard would often re-listen to a mix later and want to remix it, especially if it was to be a single. The best one being ‘Photograph’ on Ringo’s [1973] album [Ringo]. He had gotten the idea of doing the wall of sound and we certainly went for that. We had 16 tracks and the tracks were full, meaning that certain tracks had more than one instrument on them, like in the verse and chorus. We mixed it, then we mixed it again, and then we mixed it again and then took it into master [mastering – where the mix is transferred to a source, ready for copying], and he said, ‘It’s still not right,’ and we mixed it again – I don’t know how many times. Finally, in the mastering lab he said, ‘I think we’ve got it, if we just get this one element…’ and I looked at him and said, ‘Richard, you, me and that 16-track tape are never going to be in the same room again. Either I go in alone and mix it or you get another guy.’ He looked at me and said, ‘You’re kidding,’ and I said, ‘Not even a little bit.’ To my surprise, he said, ‘Go do it,’ and I did and it was so much fun.

TLM: Moving onto Tutu. You mixed the first three tracks that were recorded in LA, ‘Tutu,’ ‘Portia,’ and ‘Splatch.’ How did you get involved in the project?

Bill: I don’t really remember. I had become a huge fan of Marcus [Miller] and worked with him on a couple of albums. It’s so cute to think back because he wasn’t married when I first met him, and he came up to me and asked, ‘What’s it like to be married?’ and I said, ‘Why, are you thinking about getting married?’ and he said, ‘Yeah, actually, I am!” I had worked with [Tutu producer] Tommy LiPuma as well, so I don’t know which of them called me.

TLM: The music was a new departure for Miles, essentially, Miles and machines. What was your reaction when you first heard the music?

Bill: Pretty much like most people – shocked! What else could you be? Knowing Marcus as I did – and do – I knew it was great, and it was, absolutely great. It was absolutely out of left field. What’s so interesting to me is that ten, twelve years ago, Marcus went out on the road with some cats and played it again [the Tutu Revisited tour] in a much more typical way that might have been expected at the time. The music is great – there’s just no question about it …it really holds up. I really grew to love it, especially ‘Tutu’ – I love it to death. By the way, when I was doing Boz’s follow-up album to Middle Man, called Other Roads, I asked Marcus to please write something that Boz can put lyrics to that sounds like it came out of Tutu, and he wrote a tune called ‘Funny.’ [note: Marcus also recorded his version of ‘Funny’ on his 1993 album The Sun Don’t Lie, which was mixed by Bill].

Boz Scaggs: Other Roads

TLM: Were Tommy LiPuma, Marcus or Miles involved in the mixing sessions?

Bill: As far as I know, the mixes were done and then sent to Miles, and he loved everything – there were never any complaints. If memory serves me, only Marcus was at the mix. Obviously, it was Marcus’s show. When I mixed a lot of great albums with Tommy, he had a broader brush than a guy like Marcus, who knowing every note that was on it, knew exactly what he wanted to hear … ‘please take this up a little, take that down, make a little more out of that moment – give that its own space’, or whatever.

TLM: Did it take long to create the mixes?

Bill: They weren’t arduous, I know that. I love working very fast, especially on a record like that. I guarantee it was not a full day, probably something like six hours a song from start to finish.

TLM: Around the same time, Miles had overdubbed on a Prince tune, which was then mixed. Were you involved in that mix?

Bill: No, although I had heard that Prince was supposed to be on Tutu.

TLM: What did you think of the reaction to Tutu?

Bill: I read the reviews and I thought they were hysterical – they went the total gamut! ‘This isn’t jazz; it’s fusion schlock’! On the other hand, a highly respected jazz reviewer said it was the jazz record of the year.

TLM: That was Mike Zwerin, a jazz writer who had played with Miles back in the late 1940s. He called it the jazz record of the decade.

Bill: Wow! One thing for sure, Tutu is a Miles album that will never be forgotten.

TLM: Did you meet Miles while working on Tutu?

Bill: No, but I did later on. The following year, Tommy LiPuma asked me to go to Europe with him and record a live album with Miles on his European jazz tour. The first concert was in Nice. I got to the venue and Tommy comes up to me with Miles and introduces us. Then Miles’ road manager walks up and says, ‘Miles, the equipment didn’t arrive from the States, but don’t worry, I’ve been working all day and I’ve got it covered.’ Miles looked at him and said, ‘I don’t want no f****** rental equipment – cancel the show.’ Then he walks away. Tommy, Miles and I got into a car and went to the hotel and Miles was just muttering. When we get to the hotel and go up in the elevator, Miles is still muttering – what was the problem? He wouldn’t have to use a rental horn! The musicians were going to be fine, but maybe he just didn’t want to play – who knows?

Phil Collins singing ‘In The Air Tonight’ on the 1986 tour with Eric Clapton

Now, the great part: we’ve got the night off, so what do we do? The road manager tells me about a band that Eric Clapton has put together that includes Phil Collins on drums, [keyboardist] Greg Phillinganes and [bassist] Nathan East. It’s an all-star band and it’s playing somewhere on the coast that night. So my wife, the tour manager and I get into a car and take off to find it. With the limited French between us, we discover that it’s somewhere on the French Riviera. I don’t know how we found it, but we did. We drive around to the backstage entrance, and the tour manager jumps out and goes to the guard on the gate. He points at the car, says something, and the next thing you know the gates are opened for us to drive in! I walked up onto the back of the stage and here was Phil Collins sitting on a large speaker with a mic singing ‘In The Air Tonight.’ Then he jumps off the speaker, goes to the drum kit and plays that famous drum fill. I spent the rest of the night making faces to my friends and listening to fabulous music. It was one of my favourite nights in music. I’m friends with Greg and Nathan, but sadly, I never met Phil Collins or Eric Clapton. If you ask ‘are there artists you’d like to work with?’ Well there are two of them, especially Phil – I love his drumming, his voice and his sense of pop music.

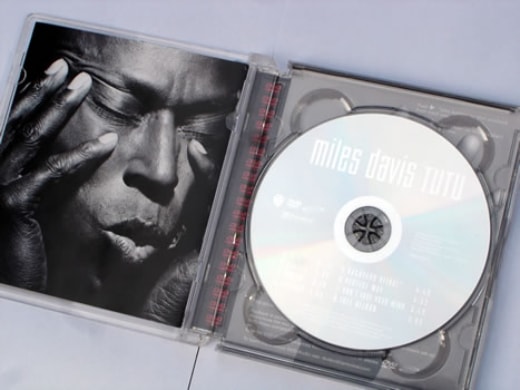

TLM: You were also involved in mixing the Tutu multi-channel DVD-Audio disc.

Bill: The story goes that Tommy was at the home of [the late Montreux Jazz Festival founder] Claude Nobs, and Claude had gotten an early copy of the multi-channel release. Claude asked Tommy if he had heard it and Tommy replied that he didn’t know anything about it. When Claude played it, Tommy went ballistic – he said the mixes were bad, they had the wrong solos and there were all kinds of other problems. When Tommy got home he called me and said, ‘I called Warners and told them that my contract says that I have to approve any mix that’s done, and they didn’t run this by me. I told them if they did that again, I would sue them for everything they’ve got.” I went in and remixed it.

The Tutu DVD-Audio disc has multi-channel audio mixed by Bill Schnee

TLM: What’s your take on multi-channel audio?

Bill: I love it. I was involved with the old Quad [four-channel] records in the early 70s. I loved it then and I loved it now. The question has always been, what do you do? Do try to put the listener in the middle of the band or basically have the band on stage in front of you, with some things bouncing around and behind you? It’s a new kind of canvas and different people are going to paint with different hues of colours.

Speaking of quad, I remember when I redid the Carly Simon album No Secrets with ’You’re So Vain’ on it, and the studio that I mixed in had a quad panner, a knob I could use to move sound anywhere between four speakers. I kept the mix pretty normal, but when that guitar solo happened, I remember moving it around the speakers; it was just a fun moment. Multichannel is a different palette, and it’s a lot like the complaints you hear from people when the first Beatles or Beach Boys records were in stereo. You get used to what it is and everything else is different – a lot of people love it; a lot of people don’t love it.

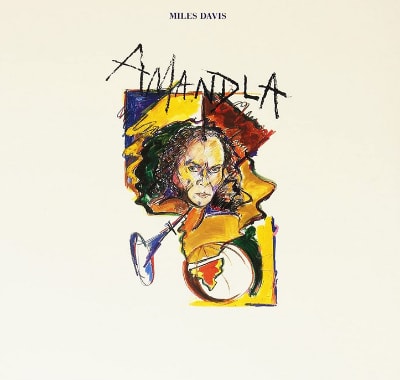

Miles Davis: Amandla

TLM: You mixed the whole of Amandla, which had more live musicians involved, and also a slicker, more polished production than Tutu. I also believe that Marcus Miller wasn’t present for much of the mixing, because of the birth of his first child.

Bill: Yes, I had forgotten that. He had basically abandoned the techno thing – for want of a better word. I don’t remember the songs being as good as the three I mixed on Tutu. There were some great moments and there was [saxophonist] Kenny Garrett, who’s a fabulous musician.

TLM: You’ve seen many changes in the music industry.

Bill: My first mentor was the engineer/producer Richie Podolor, who produced my band’s record and went on to produce bands like Steppenwolf and Three Dog Night. I hung on every word he said, and he said something once, ‘There’s no substitute for talent,’ and boy-oh-boy, have I seen that. I could do a whole twenty minutes on the fact that that was before technology became what it now is – technology has become an incredible replacement for talent. Now we can put singers in tune; change their timing, add or delete their vibrato – it’s unbelievable what you can do. It’s very sad, because at the end of the 1980s, there were no new drummers coming onto the scene in LA, and why would there be? All the records were being done with drum machines, and that wouldn’t inspire anyone to pick up a pair of drum sticks and play paradiddles.

Most musicians now learn that they can buy a DAW [digital audio workstation], Pro Tools or whatever, and they quickly learn about cut-and-paste, and the whole idea of what they don’t have to do, the computer can do. Technology has really been a major exception to that statement of Richie’s. Unfortunately, technology has become a substitute for talent to a great degree.

TLM: It’s sad that it’s getting rarer to find times when musicians play together in the same room to create music.

Bill: I moved to Nashville three years ago and I’m thrilled that it’s still going on here. In fact, last week I had a string session to do, and I called almost every studio in town that was big enough for the session. I finally found one – actually a very good one – that happened to be open. All the others were all booked! So very happy to hear that.

TLM: That’s a good point to finish on. Thank you.

Many thanks to Bill for his time and patience, especially for answering questions about the Aja sessions for the zillionth time! And a thank you for providing some of the images.

Bill’s book is a great read and can be ordered at Amazon UK and Amazon US.

Bill’s website is here: www.billschnee.com.

Thanks also to Marcus Miller for kindly allowing us to use the photo from his website: www.marcusmiller.com.