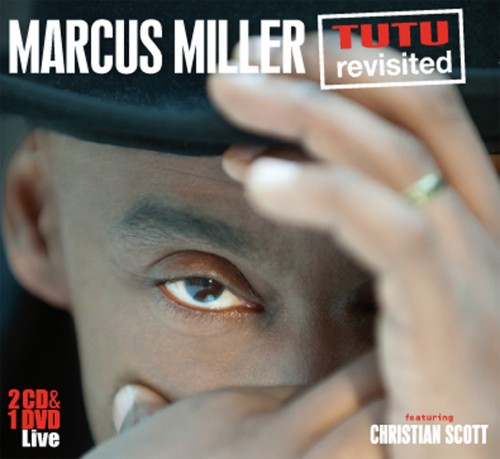

Marcus Miller talks about Tutu and Tutu Revisited

I interviewed Marcus for a piece for the May 2011 issue of Jazzwise magazine which looks at the making of the Tutu album, its legacy, and Marcus’s project, Tutu Revisited. The Jazzwise piece is long (around 2500 words) and has lots of background information on the album. There’s also a short interview with George Duke, talking about Tutu, plus a previously unpublished Miles interview from 1986 by Roy Carr, so it’s well worth getting hold of a copy (the Jazzwise magazine website has order details).

But despite the article’s length, I had to omit quite a bit of my original interview with Marcus. So here it is. When I talked to Marcus, it was a typical day in the life for him – he’d just signed off the Tutu Revisited CD/DVD package; was writing some music for his next album, whilst also preparing an album for his young saxophonist Alex Han. He was also getting ready to go on the road with George Duke and David Sanborn. Also pencilled into his hectic schedule is a series of planned gigs with Wayne Shorter and Herbie Hancock later this summer!

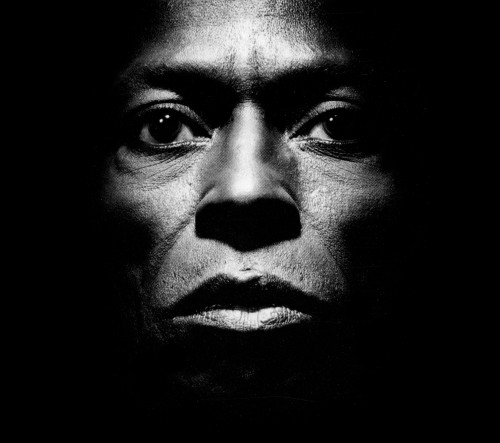

TheLastMiles.com: You’ve said that one of the problems with making contemporary music is that you never know how it will be judged in the future – will the music only exist in the period it’s made or beyond? How does it feel to know that, twenty-five years on, people are still listening to Tutu, still playing Tutu and still talking about Tutu?

Marcus Miller: That’s great – that makes me feel wonderful. There are two goals for me, primarily. One is to create something that describes the time that you’re living, and I think all artists should try and do that, in my opinion. And the second one you don’t have any control over, because how your music is viewed down the road is as much a function as what happens down the road as what happens in your music. In the funk world, you have Parliament and Earth Wind and Fire. Twenty-five years later, who knew that sampling would become a big deal and that hip-hop was going to be relying on records? And that Parliament would be sampled a lot, so people got exposed more to Parliament than EWF, at least at this point? Who knows what will happen in twenty years time? I have no idea, but it’s really beautiful to see that Tutu has developed.

TLM: Reaction to Tutu was highly polarized – in a radio interview, you recalled some people said to you, “I love that album”, others said, “You’ve ruined Miles’s career.” You laughed when you recalled this, but I wonder if any of the criticism of Tutu – it wasn’t a jazz album, Miles was a sideman on his own record, it was technology-driven – upset you?

MM: No, not at all. Honestly, it didn’t bother me at all. There are notes that Miles could have played in 1986 that would not have diminished the past 40 years. In terms of, ‘it’s not Miles’s albums, it’s Marcus’s,’ well you know man, I was there. I was the one that was inspired to come up with those things. I was the one noticing the difference between writing for him and writing for other people. His work went beyond playing the trumpet track – he was the inspiration that got me started. Plus, there was so much precedence for this; you had Gil Evans with Sketches of Spain, and Porgy and Bess. Gil would set that all up – he’d done all the arrangements, he got the musicians together and Miles came in and made it his – once he puts his presence on it, it’s his. In terms of ‘it’s not jazz’; I bought a DownBeat magazine when I was fifteen years old and they were arguing about that. The last time I looked at DownBeat, they were still arguing the same stuff.

TLM: When critics compile lists of the ten or twenty Miles Davis albums you should listen to, you get the inevitable Kind of Blue, Bitches Brew, Sketches, and for the 1980s period, they often only include one representative album, and that’s usually Tutu. Do you agree that Tutu is the most significant album of Miles’s last period?

MM: I think there were two periods in the 80s. There was the first period which started with The Man With The Horn – which is when I joined the band – and there’s the second period with Tutu. Of the second period, I think Tutu is probably the most definitive album. Of the first half, I don’t know – there was an album You’re Under Arrest, which typified where he was at the time. I do think that Tutu had a lot of elements that represented the 80s; that for better or for worse, represented where we were at, and not just musically, but as a society. The technology had just been introduced in the last ten years, and we were just struggling to figure out how to co-exist with these machines – they were making our lives better, they were making our lives worse, depending on who you talk to! And I think Tutu really represented that and I really enjoy hearing Miles in that atmosphere. Just as you have Miles in the 40s and the 50s, in the 80s, you hear him with the synth stuff and I think it was really representative of where he was as an artist.

TLM: In terms of how Tutu was created, you are often compared to Gil Evans – you worked with Gil on Star People album. What are your memories of him and did any of his working methods inspire you?

MM: When I met him, he was in New York and he was just a kinda sage character, who hung around with Miles a lot, and he hung around with David Sanborn. He’d be sitting in the back of the studio while we were working, not saying a word for hours; just listening with this vibe in his eyes, a real pleasant smile on his face. I loved the way he loved music – I love the way he enjoyed music. He wasn’t judgemental, he just listened. I remember the first time [the late bassist] Jaco [Pastorius] did a gig in New York. Gil was in the audience and I was sitting next to him. Gil heard Jaco play a broad melody that he used to play and Gil just started laughing at how unabashedly romantic Jaco’s sound was. He made a reference to some singer in the 50s that he reminded him of. He had so much joy; this common joy that he enjoyed music with, and I was really inspired by that, and thought ‘that’s what I want music to represent in my life.’ He was cool; he was the man. If you knew how much music he had in his head; if you knew how deep the guy was, but he never carried that around with him.

TLM: In the Miles Davis Radio Project you demonstrated how the music for the title track was put together. You were obviously proud of your achievement, but I also noticed a certain wariness – as if you were a magician giving away his secrets. I get the feeling that you like the fact that on the track, it’s hard to know what is man and what’s machine.

MM: Yes, because I think that my whole feeling was that the ultimate kind of example of this new age of machines was that we wouldn’t be able to tell that machines could be used so creatively; that they would simply be an extension of our humanity. So to break it down and show you was like taking the cover off. But it was something I didn’t mind doing.

Tommy LiPuma

TLM: You initially you made three demos for Miles – “Tutu”, “Portia”, “Splatch” – then producer Tommy LiPuma called for more material, which resulted in the second batch – “Tomaas”, “Don’t Lose Your Mind”, and “Full Nelson.” Was there any difference in how you approached the composition and arrangement for the later tracks? Did you feel it was a greater challenge or were you inspired by the fact that Miles and Tommy LiPuma liked what you had done?

MM: It was really inspiring that they liked it enough to say, “Let’s continue.” The challenge was the same challenge you always have when you’re making albums, which is, “okay, I’ve started the story: how do we develop this thing?” You don’t want to write ten “Tutus,” so, “here’s the story, how do we develop things and make a few detours and create a full picture?” That’s the challenge; that’s always the challenge. The main thing I felt though was excitement, and honoured that they wanted me to do it.

TLM: What impact did the Tutu album have on Miles?

MM: He said, “Thanks man you brought me back.” I think that with Tutu, Miles was like a leading artist again in the 80s, and to pull that off again! The 40s, 50s, 60s 70s and now the 80s – for almost 50 years. For each decade, he was not only relevant; you could look to him to get the feeling, the zeitgeist; the temperature of the times. I feel that the music we made helped him do that.

TLM: What’s the impact of Tutu on the music world? Some say it was a one-off with no influence on jazz.

MM: That’s just a function of the jazz world being stratified. And there are people who don’t hear the influence, but that says more about you than it does about Tutu and its influence. I go all over the place, you hear a synthesiser and a muted trumpet and it’s like – here we go again! There are people who only live in the world of acoustic jazz who aren’t going to hear it.

TLM: You once recalled the story of a person who told you that they had heard Tutu being played in a coffee shop – and it was not a compliment.

MM: I think we’ve bought into this concept that any kind of music that gives lots of people pleasure means that there’s something not profound about it. You want to talk coffee shops, for example, I’ve heard Kind of Blue in coffee shops; I’ve heard [organist] Jimmy Smith, [guitarist] Wes Montgomery, [saxophonist] John Coltrane. All it means is that music creates certain mood and that never bothered me. All these comments illuminate the people who are making the comments more than the music. If you have a problem with anything that becomes mainstream, then you’re going to have a problem with Tutu, because it was very successful. Sometimes people resent that success; they want to keep it for themselves: “I’m outside the mainstream and I want my music to stay outside the mainstream.”

TLM: What’s the legacy of Tutu?

MM: I don’t know; it’s beyond me. My only responsibility was to create and to react to the moment at the time. Miles is so much bigger than any of the individual albums that he made. The thing that I’m most proud of is, regardless what you think about Tutu, you’ve got to admit that, for a guy who was 60 years old to be creating music that had so much relevance for the time, is pretty inspiring. Most musicians who are great musicians, by the time they’re sixty, they’ve been settled in for years; they do what they do. You go to them to get a flavour of their years, but with Miles, he was committed to continue making relevant music, from day one to the day he died. Tutu was simply a chapter in that story.

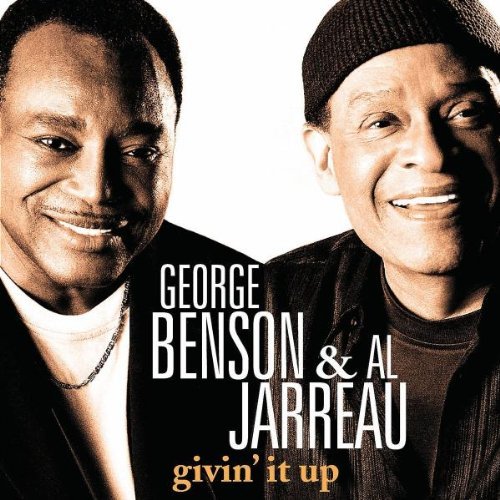

TLM: There have been numerous cover versions of “Tutu” – by Cassandra Wilson, George Benson/Al Jarreau, and others. Do you have a favourite?

MM: To me that’s like a sign that the song is creeping into the jazz language. I love Cassandra’s version; I love George Benson and Al Jarreau’s version too. Any version that tries to stay true to the feeling of the song; the atmosphere was created. Some people simply use it as a blowing tune and they’re not careful with it. Whereas people like Cassandra, they really approach the music with more care and try to figure out what the feeling of the music is.

TLM: Did you ever see Miles play any of the Tutu songs live?

MM: I sat in the audience a couple of times and saw him play “Tutu,” and “Portia” and “Splatch.” It’s always a weird feeling; not just with Miles, but any artist I’ve worked with – David Sanborn, Luther Vandross. You’re sitting in the audience and you hear what you wrote and how they changed it, because they’ve been on the road. When you’re on the road, music begins to morph – parts get added, parts get deleted – so it’s always interesting to see where the music goes. It’s almost like seeing a child turn into an adult. I remember hearing Stevie Wonder sing “Tutu” around that same time at his concert – it was an honour to hear that.

TLM: In the1989 Night Line TV show, you played “Tutu” with Miles, Kenny Garrett, David Sanborn and others – what was it like playing with Miles in that setting?

MM: It was crazy man. Tutu was such a studio project and I approached it more like it was a painting, “I’m going lay down this rhythm, then I’m going to listen to it for a bit, and then add a bass, add some chords, and eventually we’re going to add Miles.” It was like a painting – you do a little bit, you stand back and you look at it and imagine what you can add. It was a new way of making music, at least in the jazz world. Then to play it in the live realm – it was very cool to be able to make that transition.

TLM: Let’s talk about your Tutu Revisited project. I understand you were asked by organisers of the We Want Miles exhibition in Paris to play the whole album live, but you were reticent.

MM: I was reticent because I know that Miles wasn’t the type that wanted to do something like that – if they’d had asked him, he would have said no! He wasn’t the kind who really liked to look back, although Quincy [Jones] convinced him towards the end of his life [at the 1991 Montreux Jazz festival, where Miles played the classic Gil Evans arrangements, barely two months before he died]. So I was a little reluctant, but I wanted to pay a tribute to him, so I looked for an idea that might off-set that negativity. My idea was, “I’m going to find some young musicians.” Miles really loved finding new guys who could inject new energy into his music. I thought that if I could find some really great guys, although Miles might not have cared for me going backwards, he probably would have got a kick out of what we did.”

TLM: But Miles did look back. When you were in the band, he played an old tune, “Ife,” from when bassist Michael Henderson was in the band. He also played “My Man’s Gone Now”, from 1958. Later on, Miles played “In A Silent Way,” and “Theme from Jack Johnson.” In 1991, he did the concert with Quincy, and two days later, and an amazing one Paris, with many old band members. Also, Miles would have loved young people playing music from his albums. Take Digital Underground’s – “Nuttin’ Nis Funky” (a reworking of – “Fat Time.”) What did you make of that?

MM: I love that cut. It’s so funky!

TLM: Let’s talk about the members of the Tutu Revisited band. The saxophonist Alex Han you discovered while running a course at Berklee College of Music. He’s a monster player – he reminds me of a young Kenny Garrett or Donald Harrison. You’ve had two drummers, Ronald Bruner Jr and later, drummer Louis Cato, who was recommended by Alex Han. You’ve also used two trumpeters Christian Scott (nephew of alto saxophonist Donald Harrison, who briefly played with Miles in October 1986) and Sean Jones. The keyboardist is Federico Gonzalez Peña.

Christian Scott © courtesy Ivory Daniel

MM: Christian has been on the scene, maybe six or seven years. I was always drawn to him. He’s from New Orleans, but he’s not as tied to the tradition like most guys who come out of New Orleans. It’s our European city in America and really tradition-orientated. Most of its glory is in the past and New Orleans has figured out how to preserve that past. That’s what you get when you go there – it’s about the Second Line and all that wonderful tradition. So a lot of musicians come from that perspective – it’s about playing the history; it’s about playing the tradition. But although Christian has that tradition, he also is committed to pushing from time to time, and I really appreciated that about him. That’s what made me think that he’d be great for this project. The trick was that when I told the guys we were going to do Tutu Revisited, people broke out the synthesisers and everybody was getting ready to reproduce the CD! But I didn’t want to waste all the talent doing what some pop bands do, who replay a great album from 30 years ago. I wanted to start at Tutu and see where we can take it. So the first tour that we did, we used Christian and I was really happy with him. It was really challenging for him – you have to play Miles’s melody, you’re probably going to have to use the mute in a few places, but you also have to try and find your own voice. That’s not easy, but he did a great job.

Sean Jones © and courtesy Sean Jones

In the second tour, we had Sean Jones, who had recently left the Lincoln Center Orchestra. Sean was looking to do different things. He has talent – I knew he was a great player and I was really interested in what he would bring to do this. He was completely different from Christian, but just as great in his own way. So I was really happy with the trumpet situation. I first saw Federico Gonalez Peña with Meshell Ndegeocello; he was her musical director for a long time. I was always impressed by his range – he was always playing four or five keyboards at the same time, and he always thought polyphonically. I’d been using him in my own band and I thought he’d be great. The thing for him was trying to balance those synths, which say Eighties, with where we want to go. He’s got a bass synthesiser going on, he’s got voice going on; he’s got all sorts of things happening at the same time; I’m not really sure how he does it.

Federico Gonzalez Peña

TLM: I read an interview where you said that the first rehearsals and first few gigs were very emotional for you – they took you back to when you were twenty-six and Miles was sixty. Was it hard for you?

MM: It wasn’t hard, but it was definitely something I had never experienced before; that kind of nostalgia. It feels like it just happened recently, that’s how I always refer to it. If you talk to me about it, I talk as if it just happened the past year. Then to be in that museum [in Paris] and each room in that museum represented an era of Miles life – I just got lost in the story. And then you get the 80s and there’s an era where I had a small part [editor’s note: Marcus is being overly modest here!]. It was amazing to realise that you’re part of that story. For me, it’s an amazing story, especially when you realise that most musicians make their mark when they’re in their early twenties and then spend the rest of their life basically refining that: putting whatever they created into different packages. And to see a guy was unafraid, so that he could completely abandon what he was doing, even though it was successful. Miles was the biggest jazz musician in the world in the late fifties. Why would you ever change that? Wouldn’t you ride that until it died? But he went, “No man. I gotta move on.” And the musicians he associated with almost forced him to move on. He had the best guys in the world and he knew those guys weren’t going to stay around forever. He had John Coltrane in the band. There’s a time limitation because Trane’s going to move on. Miles put himself in situations – “What am I doing now?”

In the Sixties, he had Wayne Shorter and Herbie Hancock, and they created this unbelievable balance of being avant-garde and still swinging at the same time – it was a pretty amazing feat. Then he said, “Hey, we’re done with that. I need some electricity; I need Hendrix; I need James Brown.” People got on his case, but I don’t blame them, man. Can you imagine how much in love you might have been with something like “So What” and how much of a part of your life it became, like it was the soundtrack of your life? Imagine how connected you would be with that record, and then all of a sudden, the guy who had created that record said, “I’m done with that. That music is no longer relevant.” That’s going to elicit an emotional response, because in a certain subtle way, you’re telling me that I’m no longer relevant, because I’m connected to it: “You’re turning your back on the music and you’re turning your back on me.” I completely understand the psychology. Not only did he change the music, but he went to music that had different feeling, particularly from the Sixties to the Seventies.

In the Sixties, although it really advanced, the music was still based on traditional American songs before rock-and-roll revolution. So there was always a head, there were always chord changes; there was always a melody and the rhythm was always there simply to support that. Then in the Seventies, he switched to music that was more influenced by rock and more connected to African; where the rhythm was the lead and the melody was just there to give the rhythm variety. So not only are you turning your back on me, and turning your back on the music you made, you’re turning your back on the values of music that I hold dear. So either you’ve got be courageous, a genius or crazy. I think Miles was a little bit of all. That’s why he’s representative of music in America.

TLM: Looking back to when you were a 26 year-old creating Tutu. Is there anything you know now that you’d wish you’d known at the time? That makes you think: “I wish I could go back and change that?”

MM: There are plenty of things like that – always. But they’re always balanced out by the fact that, with everything I know now, would I have taken the chance to try this? Would have I had the youthful naive feeling that this could happen? So you don’t want to go back and try to change one thing, because you might end up changing a lot of things, and you might end up with something completely different. So you’ve got to always live with what you’ve done.

TLM: Watching various performances by the Tutu Revisited band (see the various YouTube videos), I’m amazed at the different slant you take on the tunes. If we take “Tutu” for example, – sometimes you play it with your bass; other times, with bass clarinet. In one version, there’s a reggae section, in another, an extended jazz-swing section. How did that happen?

MM: That’s just a function of being on the road and starting to get comfortable with the music and with the musicians. There’s this thing with jazz, that because the audience always changes, you could play same thing every night and it’s going to be new to the audience, unless they’re travelling with you from city-to-city. So you can get away with playing the same thing. But you know you’ve got the musicians with you, who heard it last night. You want to inspire the musicians and each musician wants to inspire the band, so you end up doing different things to the music every night. So Tutu, everyone knows how it goes, so after a while you start looking for windows of opportunity to jump through.

TLM: How much of the music was planned and how much improvised?

MM: No matter how long we rehearsed, the first rehearsal is the first gig, because that’s when you when have an audience and you feel an energy to the situation. We rehearsed about three or four days. All I really wanted to do was to make sure that we all knew the basic form of the songs, because I know, once we get going, that’s when things kick-in. That’s exactly what happened, and it didn’t take long, because these guys got comfortable really quickly. By the third or fourth gig we were already exploring, and I was really happy about that.

TLM: Tutu Revisited started as a one-off gig and ended up being a two-year world tour – how come?

MM: The managers would talk to promoters around the world and say, “Marcus is doing this gig,” and they’d say, “We want that! We want to bring that to Europe, we want to bring that to the States.” It seemed like an idea that was a very popular idea.

TLM: Tell us about playing the music live.

MM: The first notes were very emotional for me, man. Not emotional in terms of being sad, but every note brought back a memory I hadn’t remembered. I’ve been telling stories about working with Miles on this project for a long time. But when you start playing the notes, you remember other things; the notes trigger memories of when he said this to me or how he reacted when he first heard that note. So the first few gigs were a trip, but eventually it got easier; more comfortable. But what amazed me was that with the Tutu Revisited band, those guys were barely born when the CD came out and they would listen to the music and say, “Okay on this section, do you want me to do this or should I try that?” The sort of thing you normally get when working with musicians when you’re working on music.

But the thing that struck me was that Miles – he never asked me any of those questions. He’d come into the studio and he hadn’t heard anything. I’d be working on the song and I’d play the track for him and he’d say, “Oh yeah, that’s cool.” Then I’d write out the music for him, show where the melody went and then he just played. He just reacted – he didn’t ask me what key it was in or what the approach should be. Or I’d use some non-standard harmonies and he didn’t blink – he didn’t ask me anything. Not only was he not intimidated by my non-standard harmonies, but he played a couple of things where I had to say, ‘What did you just do?” I’d re-analyse and sometimes I’d change the harmonies, because what he did was better than what I had originally. It just made him grow in mind working on Tutu Revisited.

TLM: It all reinforces the fact that Miles wasn’t just a sideman on Tutu

MM: He would say to me, “That’s good man; write another section to go with it” – real top-line executive comments. When I worked on the Siesta soundtrack album, which we did after Tutu, I had to work really fast and have the whole thing done in two weeks to make the film deadline. I got to the last scene and I wrote a couple of things and the director Mary Lambert was like, ‘It’s not quite there,’ and after a couple of tries, I’m thinking was striking out, I told Miles I was hitting a brick wall. So Miles said come up to my house – he lived up in Malibu – and he put me in an empty room with a music player and all this Spanish music and he just closed the door – that was his contribution! When I came out of that room I had it and I went back to the studio and recorded what I wrote. The director came in and I played the piece for her, not looking at her. When I do look, she’s completely in tears, like overwhelmed by the music. That’s how Miles would do it; no specific direction, just kind of point you, “Look in that direction, you’ll find it.”

TLM: Now I know this is a bit like choosing your favourite child (!), but which tunes from Tutu did you get the most pleasure playing?

MM: Well, I knew I’d enjoy “Tutu” and I’ve been playing that with my own band for some time. The other obvious ones are “Portia” and “Splatch”. But you know the second side of the album – nobody knows there’s a second side! There’s a song called “Don’t Lose Your Mind” – with a reggae feel – that was the most surprising. It’s like the most obscure song on the CD but I really like its vibe and that opened up for me into something that was really nice. [Editor’s note. On the Tutu Revisited CD and DVD, the band play an extended 19-minute version].

Felton Crews, Miles, George Duke at Montreaux – © George Duke

TLM: “Backyard Ritual” was the only track from Tutu that Miles never played this live. Now you’ve played it for first time with live instruments. I know George Duke always wanted to hear a real saxophone on the track, so has he heard your version?

MM: George and I are getting ready to do some work together [they are playing a series of concerts with David Sanborn this spring] so I’m going to hit with him with a couple of versions. It was George’s demo of “Backyard Ritual” that let me know that Miles was willing to move into this other direction. George was using the Synclavier, which was the big techno keyboard at the time, and a drum machine. I heard it and I got excited, “Oh, Miles is willing to go into this direction – excellent,” and that’s when I wrote “Tutu”. George had a lot to do with the whole sound of Tutu.

TLM: David and George played a few tracks from Tutu with Miles at the 1986 Montreux jazz festival.

MM: When I started doing in my thing in New York, I was in really separate camps. I was playing with Luther [Vandross] which was completely R’n’B funk; I was with Sanborn which was contemporary jazz, and I was with Miles, which was kind of a more progressive jazz-funk. There was not a lot of crossover. But then I managed to have Dave meet Miles, which was great. Luther meeting Miles – there was no music. Ever had two friends where you think, “I’m not sure whether they should ever meet?” But they got a kick out of each other, because they had respect for each other. I have really fond memories.

TLM: Miles did a lot of guest appearances on other people’s albums in the 1980s, and I’m surprised Miles and Luther never did get together, especially with your connections. It would have been amazing.

MM: Thanks for telling me thirty years too late!

==

Many thanks to Marcus for his time, and special thanks to Bibi Green, for helping to arrange the interview with Marcus.

Tutu Revisited can be ordered from Amazon UK and Amazon US

Check out other Tutu links on www.thelastmiles.com:

Peter Doell (engineer for the first sessions in California)

Eric Calvi (engineer for the New York sessions)

Jason Miles A profile of the man who did much of the programming on Tutu

Tutu DVD-Audio version – A review of the DVDA reissue