I don’t know where the years have gone since TheLastMiles.com was updated. Sadly, in that time, a number of people I interviewed for my book or this website have died, and this is my tribute to them.

Bucky Pizzarelli (1926-2020)

I’ve always been fascinated by the period when Miles began incorporating the electric guitar into his music. That was why I was thrilled to interview Bucky Pizzarelli, who was the second guitarist Miles used after Joe Beck. Bucky (who was born in the same year as Miles) played on a 1968 session for the track “Fun.” After Bucky, Miles tried out George Benson, who is often mistakenly credited as the first guitarist Miles used, because his playing appeared on the 1968 album Miles in the Sky. “Fun” finally appeared on the 1981 compilation album Directions.

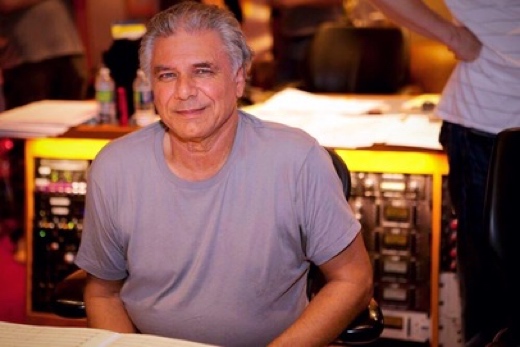

Bucky Pizzarelli: Photo by Mike Orla, Courtesy Benedetto Guitars

Bucky had a 75-year career that spanned everything from big bands to television bands, and session work to solo guitar. He also pioneered the use of the seven-string guitar. I really enjoyed interviewing Bucky, in fact I would go as far as to say I have never interviewed a nicer person – and I’ve been lucky enough to speak to many lovely people during my writing career. I was not surprised to read that no one had a bad word to say about him. I feel grateful to have had the chance to speak to a true guitar legend. Bucky’s modesty shone through throughout our interview and I was delighted that one of things he said to me was used in a number of Bucky’s obituaries: “Every day I get up and I try to correct what I screwed up the night before!”

Wallace Roney (1960-2020)

Wallace Roney was one of the finest trumpeters of his generation. He was a huge talent, who had had lessons from trumpet giants Clark Terry and Dizzy Gillespie, and who Miles had personally mentored. The connection with Miles crystallised at the 1991 Montreux Jazz Festival, when Miles played his last concert at the event. Miles surprised and delighted many fans by deciding to play the classic Gil Evans arrangements from the late 1950s for albums such as Porgy and Bess, and Sketches of Spain.

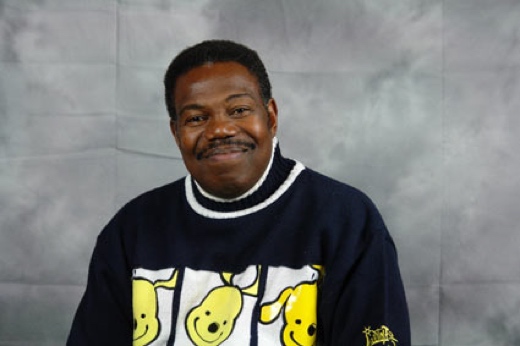

Wallace Roney and Miles at the 1991 Montreux Jazz festival

Wallace told me how he had been a member of the George Gruntz Concert Jazz Band and was pleased to hear the band would be performing at Monteux, “I thought, ‘great, I’ll be able to catch Miles at the concert’. But when we got to Montreux, George informs us that we’re playing at the concert!” And Wallace was in for a bigger surprise once he arrived at Montreux. Miles was late for a rehearsal and so Wallace stepped in and played Miles’ parts. Hours into the session, Miles appeared and instructed Wallace to continue playing, and then joined him on the bandstand.

At the next day’s rehearsals, Miles gave Wallace more parts and began sharing solos with him. Then Wallace learnt that he would be playing alongside Miles at the concert. Miles was very sick at this time and had less than three months to live. Nevertheless, he gave it his all, and Wallace was there on hand to jump in if Miles was faltering. What is clear looking at the video footage of the concert is the respect and affection both men had for each other. “At the end of ‘Blues for Pablo,’ when he let me take over, it was the passing of the guard. Man, it was incredible,” Wallace told me. At the end of the concert, Miles smiled at Wallace and jokingly waved a towel over his face as if you say, “Man, you were hot!” He also gave Wallace one of his trumpets.

Following Miles’ death, Wallace played with Tony Williams, Herbie Hancock and Wayne Shorter in the A Tribute to Miles band. Although Wallace had a strong connection with Miles, he also had his own voice, and produced an impressive body of work – his 2000 album No Room For Argument is one of my favourites. Wallace has left us far too soon, but he has left behind many remarkable musical memories.

Paul Buckmaster (1946-2017)

Paul was one of the last people I interviewed before my Miles book went off to the publisher for production in early 2005. I was very lucky to include him, because he had so many interesting things to say about Miles. Quite often, when you interview someone, you soon lose contact afterwards, but Paul and I stayed in touch up until his death.

Paul Buckmaster © paulbuckmaster.com

Paul was a remarkable man. A talented cellist, arranger and composer, the musicians he worked with – Miles, David Bowie and Elton John, to name but three – tells you all you need to know about how gifted he was. He was also probably the most intelligent man I have ever known – his intellect was astounding and I often marvelled at the width and breadth of his interests and knowledge – and sometimes struggled to keep up with his thought processes. But Paul was also a modest man and I was forever telling him that he ought to write his memoirs, as no one else had worked with Miles, Bowie and Elton.

We kept in touch by phone, email and Skype video, and Paul would often chat at what was the middle of the night in Los Angeles, where he lived. My biggest regret is that we never met face-to-face. Paul had many interests aside from music, including politics and the environment, and he would often send web links or news reports about an issue that was close to his heart. Paul worked with Miles on three occasions – in 1972 on the On The Corner album; in 1979 when Miles was considering a return to music, and in 1986, when Miles asked him to compose some music for his first Warner Bros album. Sadly, none of these collaborations turned out to be a fully satisfying experience for Paul musically – On The Corner didn’t turn out as Paul had anticipated, although many years later he was proud of the album and its subsequent influence on other musicians; Miles failed to turn up for the 1979 session, and Paul’s music was never used for what became the Tutu album.

But Paul had lots of warm thoughts about Miles and said that Bitches Brew was one of the greatest pieces of music ever released. He last saw Miles in 1989 in London, when he went backstage to meet him. Paul shared the same birthday as my wife and last year, he sent a music file of him playing a birthday tune for her, which we will treasure. It was a great shock to hear of Paul’s death and even now, I still can’t believe there won’t be an email or a call from him ever again.

Ndugu Chancler (1952-2018)

Leon “Ndugu” Chancler didn’t play with Miles in the 1980s, but I chatted to him about his time with Miles, when he joined the band as a nineteen year-old drummer for the 1971 European tour. The tour wasn’t a happy one for Ndugu, who left the band at the end of it. But Ndugu had good memories of Miles, “I don’t regret it because it changed my direction and it set me up to be who I am now,” he told me. “I learned so much and it did so much for me. Miles taught me how to grow up. Forget I lost the gig: I learned more than I could have possibly learned on the gig. In the long run I learned more about Miles. Things worked out in the long run in that I went to Miles Davis school. Funnily enough, Miles and I became better friends later.” Miles used to say to musicians if that if things didn’t turn out, it didn’t mean that you couldn’t play – it just meant that he was looking for something different. And indeed, Ndugu’s talents were recognised by artists such as George Duke, George Benson, Stanley Clarke, Herbie Hancock and Frank Sinatra, although he’ll probably be remembered most of all for being the drummer on Michael Jackson’s “Billie Jean.”

Ndugu Chancler © Drummer World

Pete Cosey (1943-2012)

Pete Cosey was a phenomenal musician who never got the recognition he deserved. A superb guitarist who developed a unique tuning system, he also played keyboards and percussion. Pete joined Miles’s band in 1973 and stayed with him until 1979. Pete’s playing on albums such as 1975’s Agharta and Pangaea, sounds innovative, fresh and exciting today. When Miles dropped out of the music scene in mid-1975, Pete and the rest of the band played a number of sessions in 1976, but then the work dried up. Pete kept in close touch with Miles during this time, and was involved in a number of abandoned attempts to get Miles playing live or back in the studio.

Pete Cosey © Audrey Cho

I interviewed Pete several times – for my book, for this website and for a Jazzwise article I wrote about the On The Corner boxed set. The thing that stands out for me when I remember Pete is that he was a quietly spoken, modest man, with a ferocious memory – his power of recall was astounding. When I asked him about the time when he was recruited by Miles (an event that had occurred more than thirty years earlier), Pete not only recalled how he had been reluctant to join Miles’s band and had instead, recommended some guitar students he was teaching at the time, but he rattled off the students’ names as if it had happened yesterday!

After leaving Miles, Pete struggled to get work, partly because of music business politics, but also because as Pete admitted to me, he didn’t always make the right calls. He was also very difficult to contact, which didn’t help. But his talent and integrity were undiminished, and one of the last things Pete said to me still resonates today: “I wasn’t living an easy life. I went through a lot of great struggles but I kept true to the music. I never lost sight of that. I never stopped experimenting, improving and crystallising and creating and I still do that and I never lost sight of that. I realised a long time ago what my mission is and I’ve stayed true to that.” He most certainly did.

George Duke (1946-2012)

I first spoke to George Duke in 1998. I emailed his website and he replied, giving me his studio number. When I called the number, his lovely wife Corine answered and then put George on the line. To say I found the situation overwhelming would be an understatement. George Duke was one of my musical heroes – in my late teens and twenties I had devoured his albums – Reach for It, Don’t Let Go, Follow The Rainbow, Master of the Game and A Brazilian Love Affair. When I listen back to the interview, I can hear how nervous I was, but what is also clear is how patient George was and how he quickly he put me at ease. I had hoped to write a feature about George for a jazz magazine, but the editor I approached turned it down, adding that George “Wasn’t really a jazz player.” That was the problem he faced: George could play anything – jazz, rock, pop, fusion, Latin. He even composed an opera. He was hard to pin down musically and had an open mind to music – this was a man who had played with both Frank Zappa and Cannonball Adderley. It is probably why he got on so well with Miles.

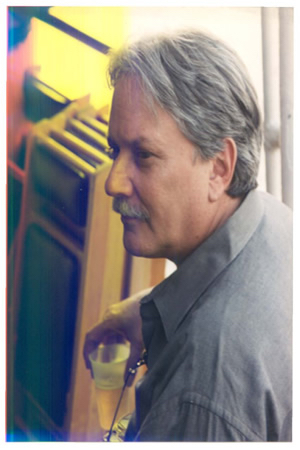

George Duke and George Cole at Ronnie Scott’s Jazz Club

Five years after I first called George, I called him again, this time asking for an interview for my book. He readily agreed and was soon recalling a host of anecdotes about Miles, many of them hilarious. George was a fun person, with an infectious laugh. He was quite simply, one of the loveliest people I have ever known. You always felt better after speaking to George. I interviewed him several times and saw him play live a few times (including a memorable gig at Ronnie Scott’s in London). In 2012, Corine died and I didn’t know that George had leukaemia. A couple of months before George died, I emailed him with a query about Miles, which he helped me with. I ended my email by saying that I looked forward to seeing him again the next time he was in London, not knowing that this would never happen again.

Tommy LiPuma (1936-2017)

Tommy LiPuma was a multi Grammy-winning producer, a big name in the music industry, who had worked with many artists including, George Benson, Al Jarreau, David Sanborn, Earl Klugh – and Miles. He was the sort of person you never expected to interview unless you were a well-connected journalist. So, when I contacted his PA with an interview request, I wasn’t optimistic about my chances. So, you can imagine my surprise when she replied that he would talk to me about Miles and gave me Tommy LiPuma’s home number.

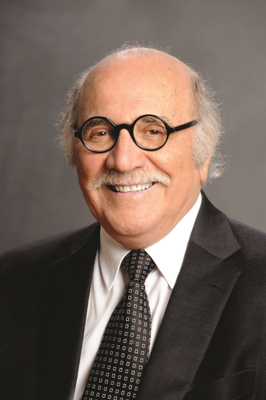

Tommy LiPuma © Cuyahoga Community College

This gives you the measure of the man and also shows the high regard he held for Miles. Tommy LiPuma had a reputation for smooth, polished productions, but he also had the vision and foresight to encourage Miles to go down a new route that would lead to the ground-breaking Tutu album.

The interview went well, even though he had builders in the house and every so often, would break off our chat to give them instructions! It was kind, gracious act to grant me an interview and I felt very fortunate to include Tommy LiPuma in my book.

Jim Rose (died 2014)

I was really pleased when I finally got to interview Jim Rose for this website, because he had been a key part of Miles’s professional life for fifteen years. Jim was Miles’s road manager from 1972 to 1987, and in his autobiography, Miles said he was, “The best road manager I ever had.” When I spoke to Jim, he revealed some of the qualities that made him a superb road manager – a sharp mind; an air of unflappability, an excellent memory for detail and a dry sense of humour. Even though Jim’s time with Miles ended on a sour note, Jim retained much affection for him and they still saw a fair bit of each other. When I asked Jim about his memories of Miles, he said: “I get a warm pleasant feeling because I really loved the guy, even though I got four stitches to show for it from another time when he hit me. He was a real bastard at times, but when he was good he was just great. He was one of the funniest and smartest human beings I ever met in my life.”

Jim Rose © Estate of Jim Rose

Ricky Wellman (1955-2013)

Ricky “Sugarfoot” Wellman was one of three musicians who joined Miles’s band in 1987 and who stayed with him until his death in 1991 (the others were lead bassist Foley and saxophonist Kenny Garrett). The fact that Ricky remained with Miles for so long tells you how highly Miles thought of his playing. Ricky had been a member of Chuck Brown and The Soul Searchers, based in Washington DC, and was one of the forces behind the Go-Go beat.

Ricky Wellman © Estate of Ricky Wellman

The story goes that Miles heard a tape of the band, fell in love with drumming and got hold of Ricky’s number. When Miles called Ricky’s home, Ricky was asleep and his wife answered the phone. She didn’t know who Miles was and told him that her husband was resting and that he should call back tomorrow! When Ricky heard what had happened, he couldn’t believe it! Fortunately, Miles’s management called the next day and Ricky was on his way. There was no audition – Ricky was sent a concert tape to learn.

Back in 2011, Ricky wrote a piece for this website in which he described the shaky start he had had with the band. But Ricky went onto become the rock of the group, who could lay down a groove, whip up a storm or play as delicately as a petal blowing in a light breeze. Miles would often give him long solos when playing “Carnival” in concerts.

Ricky’s career post-Miles was mixed: he recorded with Kenny Garrett; toured with Carlos Santana and played with Wayne Shorter and Herbie Hancock. He was also part of ESP2, a group that played tribute to the music of Miles Davis and included other Miles’ alumni, such as Randy Hall, Adam Holzman and Robert Irving III. But Ricky also for a time moved into the IT industry to better support his family. Miles’s youngest son Erin describes how close his father was to Ricky, “He and Ricky had a very special relationship for a long time. They really worked well together and they really enjoyed playing with each other. He really loved Ricky.”