Tony Hall was a truly remarkable man. He was a man for all seasons and arguably nobody has worn so many hats (all of them successfully) in the music industry as him. Over seven decades, Tony was a compere, critic, columnist, reviewer, copywriter, product manager, publisher, TV presenter, producer, manager, promoter, deejay and more. His various roles saw him associated with a wide range of artists including, The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, The Who, Jimi Hendrix, Otis Redding, Phil Spector’s artists, Scott Walker, The Bee Gees, Elton John, Joe Cocker, Loose Ends, The Real Thing and Black Sabbath.

But Tony’s biggest passion was for jazz, and his second wife was the Trinidadian jazz singer Billie Laine. He produced an array of jazz artists including, Ronnie Scott, Tubby Hayes, Jazz Couriers, Dizzy Reece and Victor Feldman. In 2002, Tony joined the Jazzwise magazine team of reviewers, a role he kept for 17 years. Tony met Miles Davis in 1954 and they remained friends up until Miles’ death in 1991. Whenever Miles visited London, he would almost invariably meet Tony. Tony also managed the late British arranger/composer Paul Buckmaster, and was responsible for Paul working with Miles several times, including on the ground breaking 1972 album On the Corner.

Tony was born in Avening, Gloucester, England in 1928 and died in June 2019. For an in-depth look at Tony’s career, you can do no better than to read the superb obituary in the August 2019 issue of Jazzwise (order a copy from www.jazzwise.com).

The interview below took place in 2007, when I was researching for a feature on the then newly released On The Corner boxed set. Tony talked about Miles; Paul Buckmaster; On The Corner; Elton John; the music industry; Miles’ 1980s period and the various musicians in his bands; the state of jazz in the 21st century, and the decline of physical music formats. Listening back to the recording, I was struck by how modest Tony was (you really had to work hard to get him to acknowledge his accomplishments) and how funny he was – he had a great sense of humour. As I said; a truly remarkable man.

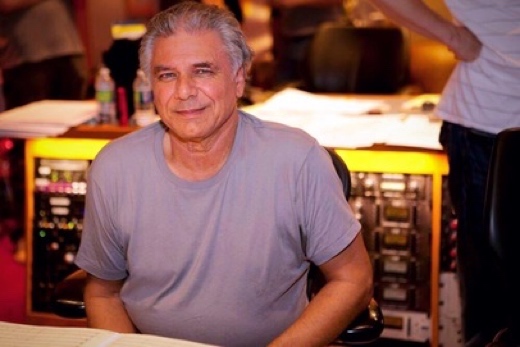

Tony Hall January 2019 © Leigh Pearson

The Last Miles: Can you tell us how you first met Miles?

Tony Hall: I was a young lad at the time and made my first trip to Paris. I sought out the legendary Club Saint-Germain, and I was sitting at the bar, when this black guy sat down next to me. I knew who he was but I didn’t say anything, but somehow, we got talking – I think it was Miles who spoke first, which was nice. At the time, he was in love with Juliette Gréco and she came in the club that night to see him. Miles wasn’t playing, but [pianist] Bud Powell was – it was the only time I saw him. He had one of his fits and just stood up and stared at the audience, before his minder took him away – he was playing brilliantly until he freaked, which was a shame [sadly, Powell had psychological problems].

I told Miles that I was doing a bit of jazz production. I was producing Dizzy Reece, a Jamaican trumpeter who was really good. Miles gave me his address and I sent him some test pressings of Dizzy. The next thing I heard was from musicians coming back from New York and telling me that Miles was singing the praises of Dizzy. When Miles’ next record came out, Dizzy called me up and said, “Hey, he’s stolen some things from me!” With Miles, you took him on his own terms.

TLM: What was Miles like as a person?

TH: I don’t know how many people really knew Miles because he was a Gemini – he was one thing one day, and another the next. All I know is that he treated me with great respect. For a young white guy who was trying to produce jazz records in England, to be acknowledged by the great Miles Davis was quite something for me – I felt very flattered.

I was honoured to be able to get into his dressing room – he was always pleased to see me and Billie. Most of the conversations ended up about clothes and shoes. Miles used to wear ladies’ shoes on stage and his toes were all cramped – he had terrible feet!

He could be difficult and one time when I went to his West 77 Street House in New York, I had a very bad experience. I had found this fantastic singer in Jamaica, Ernest “Shark” Wilson and we were doing an album in New York. Billie and I took him to meet Miles. What we didn’t know was that Miles was probably in his heaviest coke period (it was around 1973/74) and it was quite terrifying. It was snowing outside and we were let into the house. Miles eventually came in. Miles’ eyes entered about three hours before the rest of his body. He was on a very heavy racial kick and said, “What are you managing this guy for?” He said to my wife, “You should be managing him. He’s black, you’re black; you should be looking after him.” That was the only time I ever had a racial problem with Miles.

Paul Buckmaster ©paulbuckmaster.com

TLM: How did you get to manage Paul Buckmaster?

TH: Paul did some string arrangements and they were brilliant. Then I met Paul and he was one of those people who have stars instead of eyes – he looked like a star. He was very impressive. He didn’t have a manager and I said “let me do what I can for you,” and I ended up throwing him in the deep end with all sorts of sessions. He acquitted himself with great distinction. He was on so many number one records; he worked with Bowie. I was partly responsible for putting together the production team for Elton John. [Elton’s producer] Gus [Dudgeon] needed an arranger and I pushed for Paul. Steve Brown from Dick James’ office was looking after Elton, and after a series of meetings, I got Paul adopted for the gig. It was a gig that went on for several albums. Paul and Gus worked very well together.

TLM: Tell us about Elton John.

TH: I used to know him as Reg Dwight. My office was in Noel Street [in Soho, London] and there was a very famous store on the corner of Berwick Street and Noel called Music Land. Reg used to go to the store and come out with piles of import soul albums. I got to know him reasonably well on an informal level – we used to chat about the albums we were buying. He was very nice and gave me a name check in one of the books about him, saying that I was one of his favourite deejays at the time; that was really nice.

TLM: Paul has strong views about the line between composing and arranging.

TH: Paul was very bitter that he didn’t get any royalties from the Elton John things, but to be honest, no arranger in the world got royalties in those days – absolutely none. Considering all the millions of albums that Elton sold, it was very unfair, but that was show business. No arranger until much later got points [which give you a share of the royalties]. Dick James employed someone who had a famous catch phrase, “Coins in a tin can” – dreadful. He was as mean as hell. I eventually got a £250 arranger’s fee for Paul, but no arranger at the time got more than that. Nobody knew that Elton was going to be that big.

TLM: Did you have much to do with Dick James?

TH: No. Thank you.

TLM: I believe during the 60s, 70s and 80s you spent some time with Miles whenever he was in London.

TH: Miles got on well with my wife and she knew all the fashion people in the 1960s. We took Miles to see [fashion designer] Ossie Clark and Ossie made a load of shirts for Miles. My wife knew this fashion boot maker in Shepherd’s Bush – Miles was a boot and shoe freak – and he made Miles some snakeskin boots with very high heels.

TLM: In 1969, you introduced Paul Buckmaster to Miles. Why did you do that?

TH: Because Paul was a Miles fan – he worshipped him. Paul was very much into jazz. I knew Miles wanted to go in a different direction – I’d heard that he might be interested in contemporary classical composers and knew that Paul was well-versed on Stockhausen and other contemporary composers.

I had a flat in Mayfair at the time and Miles came to the flat. I introduced Paul to Miles and they just talked. One thing led to another and eventually Miles called me and I got Paul over to New York to stay in Miles’ house and work on On The Corner. Paul was absolutely over the moon to be asked to work with Miles. I’m delighted that Paul is getting some recognition for his contribution.

On The Corner boxed set

TLM: What did you think of On The Corner?

TH: I liked it very much. Part of my career has been managing black groups in England, so I was heavily involved in the soul and R&B scene. Listening to some of the extended versions on the boxed set, they do go on a bit! But the impact of the original album was very striking for me, although critics didn’t seem to like it. I felt the same about Big Fun [Paul Buckmaster worked on one of the songs on this album].

TLM: I’ve always felt that Paul Buckmaster should be better known.

TH: He’s highly regarded in America. He doesn’t seem to get offered the big names anymore. Sadly, he seems to get offered young groups and singer/songwriters, which is a shame.

TLM: What did you think of the music Miles made in the last decade of his life?

TH: I was always a bit concerned when he started bringing rock guitarists on stage. I didn’t like the music as much, but I was knocked out when he brought Kenny Garrett into the band, because I thought at least he was a serious jazz player who played the blues. It went back to Miles and Bird [Charlie Parker] a bit.

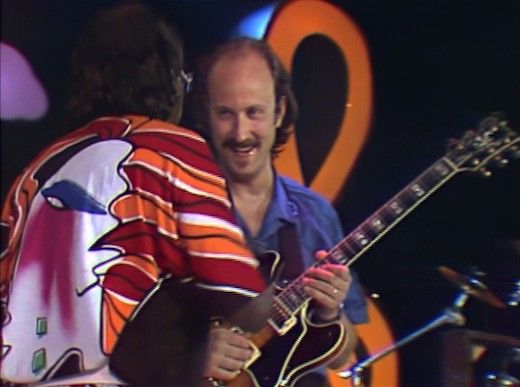

Kenny Garrett by ©Keith Major – kennygarrett.com

TLM: What about the other saxophonists?

TH: He had a succession of white saxophonists. Bill Evans played a lot of soprano and after Miles, went into fusion. Rick Margitza was good and also went into fusion. Bob Berg was very good and the most serious jazz player of the lot. I thought that post-Miles, Berg became a really fiery musician. I have a number of Gary Thomas albums, but I can’t remember seeing him with Miles. They were all good players, but then Kenny Garrett came in and blew them all away.

Bob Berg and Miles

TLM: What about guitarists?

TH: I liked [John] Scofield. [Mike] Stern was too much feedback. Robben Ford was as cool as ice. Foley was such a showman.

Miles and John Scofield

TLM: Bassists?

TH: Marcus Miller was something else when he came onto the scene. Before Marcus, there was Michael Henderson with his simple, soulful bass riffs, which were very effective. Then Marcus came in and amazed everyone with his thumbing.

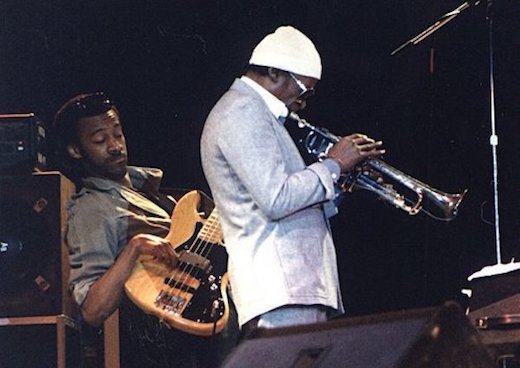

Marcus Miller and Miles

TLM: What did you think of Miles’ later albums, especially Tutu and Doo-Bop?

TH: Can anyone seriously say that Doo-Bop was serious jazz? It was Miles trying to appeal to the hip-hop audiences. Personally, I find that funk and hip-hop are restrictive for musicians to improvise over because of the lack of chord sequences. All funk players – however good – all seem to sound the same. I respected him for trying, and had he lived, something interesting might have come out of it, because they were really demos. Tutu was Marcus doing all the charts. I’m a little old fashioned; I prefer the Gil Evans collaborations. To be really honest, I was a little disappointed with his last decade of music.

TLM: Did you ever meet Gil Evans?

TH: No, but Paul [Buckmaster] did. Paul smoked quite a few joints with him!

TLM: How long did you continue seeing Miles in London?

TH: The last couple of times he came, I was disappointed about the music – I wasn’t knocked out anymore because he wasn’t playing that much in the end. He was being very friendly to audiences at that stage, but there wasn’t much jazz. I last met him a couple of years before he died, at the [Royal] Festival Hall.

TLM: What period stands out for you in Miles’ amazing musical legacy?

TH: The great quintets of the 50s and 60s. I felt the 60s band could have gone onto even greater things. Today, you have the Wallace Roneys of this world still trying to extend what Miles started in this period.

TLM: What do you think of today’s jazz music scene?

TH: I still get excited by the best of today’s music, especially African, Cuban and North American mixtures. My concern is that everybody is concentrating on technique – the feeling that should be there isn’t always there. There are too many notes. I’m old fashioned and think that jazz musicians should be human and have failings like the rest of us. They should fall flat on their faces onstage at times, like the rest of us. There aren’t the characters or personalities that there used to be. The great players – the Dexters [saxophonist Dexter Gordon]; the Lesters [saxophonist Lester Young]; the Dizzys [trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie] – all these people a long gone era. Miles was probably the last of them. He had his own mystique. It’s all too clever and technically obsessed, and the musicians all end up sounding the same, which is sad .If you heard records from the top three or four current hot tenor players, you’d be hard put to tell who was who. Back in the 50s, everyone had an identity of their own.

Tony Hall in the 1950s. Tony is standing in the doorway © Tony Hall

TLM: Will the pendulum swing back?

TH: It’s too late – it’s long gone I’m afraid. Now, when I buy my copy of Downbeat and look at the record reviews, I’ve never heard of 80% of the names. If I heard the music, I’d say “What the hell has this got to do with jazz?” I’m afraid I’m a boring old fart! [editor’s note: Not true! Tony continued to champion new young jazz talent right up to the end].

TLM: Do you think the days of the physical disc are numbered?

TH: Sadly, I do. I think it’s a great shame. To want to download one track is sad, because an artist puts a year to eighteen months of his life into doing ten tracks or so on his album. Most are as good as the other nine tracks.

TLM: What are you doing today?

TH: Living one day at a time – I’m so fucking old! I took a sabbatical from jazz for about twenty years, from 1965 to 1985, because the avant garde really made me ill – I just didn’t like it. Then, I was in Brighton one day and I saw this black trumpeter getting off his bike, setting up a rhythm box and playing trumpet to it. He was fantastic and I thought, “This is bebop!” I got talking to him. He took me back to his digs and played me things like The Jazz Messengers I found that I remembered all the solos note-for-note and it all came flooding back. Then a friend of mine who was editing Vox [magazine] said, “You should be writing again, because I had done a lot of writing in the 60s for Record Mirror – I had a column called All Ears, which influenced lots of musicians, I’m happy to say. He said start doing some CD reviews. I didn’t have a CD player at the time, but now have got a collection of around 7000 CDs. I am eternally grateful to him. I try to keep up with all new developments.

With thanks to Tony Hall.

Many thanks to Jon Newey, editor-in-chief Jazzwise, for providing this lovely photo of Tony, taken by Leigh Pearson, just a few months before Tony’s death.