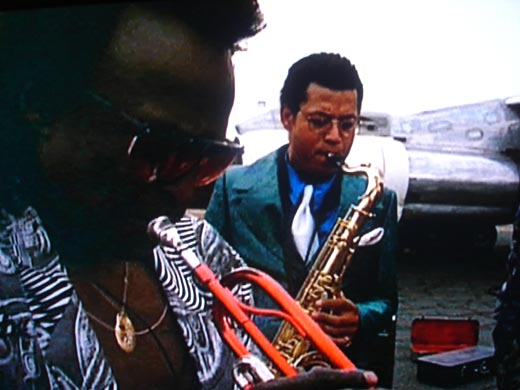

In the last ten years of his life, Miles Davis pursued three artistic careers: as a musician, an artist and as an actor. It was in the latter role that Miles starred in his only full length movie — Dingo. Dingo was a joint French/Australian production, set in the Australian Outback and Paris. The film is about John “Dingo” Anderson (played by Colin Friels), whose life is transformed, when as a small boy, he sees American jazz trumpeter Billy Cross (played by Miles) make an impromptu performance on the airstrip at Poona Flat. Billy Cross tells Anderson, that if he’s ever in Paris, to look him up. Fast forward more than twenty years and Dingo Anderson is now a married man who hunts wild dogs (Dingo) by day and plays jazz trumpet at night. His dream is to go to Paris and find Billy Cross…

Talking about Dingo, Miles said: “I enjoyed the script because it avoided the stupidities that you usually get with films about jazz musicians. I felt close to Billy Cross and, even if that’s not really the case, I could bring him to life. With my music, I am in the habit of being treated like a king. But for the movie I wasn’t exalted and alone.” Before the film was made, Miles worked with French musician Michel Legrand on the soundtrack — the two men had worked together on Legrand’s 1958 album Legrand Jazz. “Michel Legrand works very quickly. I had the problem of following him but we understood each other very well,” said Miles, “I tried to rediscover the sound, the ambience of my cool period, the style of Kind of Blue, Sketches of Spain and Milestones.”

The Last Miles was fortunate to speak with Dingo‘s director, Australian Rolf de Heer, on the making of the movie, Miles as an actor — and how they had planned to work together on another movie. It also features details of what must be the biggest wind-up Miles ever played on anyone — and he did a few of them in his time!

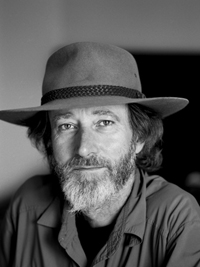

Rolf de Heer © John Elliott, donated to

the Australian National Portrait Gallery

TheLastMiles.com: How did you get involved with Dingo?

Rolf de Heer: I had a very good friend Marc Rosenberg, with whom I’d been to film school. He began writing a screenplay we’d discussed in his living room. He had a number of ideas and I said “that’s a good one,” although it was nothing like what Dingo became. He worked on that script for — I think — eight years. It was a script I loved a lot from the very beginning. At one stage during this process — after numbers of drafts and numbers of attempts to get it financed – Marc and I did a film together called Encounter at Ravens Gate, and at the end of that, Marc offered me the script. I said “no,” because it was Marc’s dream and I just thought: “Marc really needs to work with someone else.” Things happened over the years and he offered me it again — this would be around 1989 — and at that stage, we set about getting it financed.

TLM: You said you loved the script. What was it that you attracted to it?

RDH: It was beautifully written and it was about the fulfillment of dreams and the avoidance of regret — now I like that a lot!

TLM: Was Miles always considered for the role?

RDH: Miles came into the picture quite late. There had been numbers of different people talked about over the years as to who was going to play the role and at the time Marc and I were working closely together, it was going to be Sammy Davis Jr, because Sammy could play the trumpet; [he] was an actor; [and he] was an interesting name — if he could have pulled it off, it might have re-invented him as an actor, because I don’t know if he was very highly respected as an actor. He’d read the script and he loved it and desperately wanted to do it — I think he would have paid to do it.

Marc and I went on a survey in Outback Western Australia and we kept hearing about delays with Sammy and we didn’t know what was going on. It turned out that he had his terminal illness [throat cancer], which they couldn’t say anything about. By this time, we had a connection in America, a guy named Hillard Elkins, who had worked with both Sammy and Miles. And from Hillard came the suggestion of Miles Davis. At that stage, I was told that the film would be financed if Miles did it.

TLM: What was your reaction when Miles’s name came up?

RDH: My reaction was “Oh my God, no! No way!” Then I was told, “Look, it’s okay. You can go see Miles and if you don’t like him, you can say no.” And I knew that was a non-offer, because if I said “no,” the film would fall apart, so I had no choice but to say “yes.”

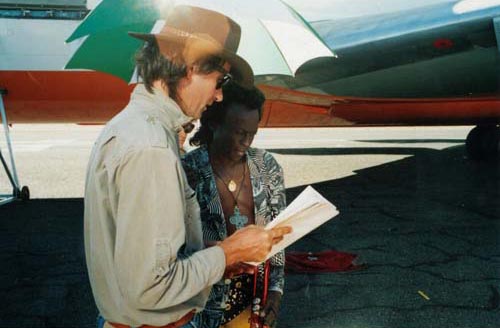

Rolf and Miles on location © and courtesy Vertigo Productions

TLM: Why were you so against Miles taking the role?

RDH: His reputation. It was a difficult film and to put somebody in that situation who hadn’t acted in a film, I thought “Nah — it’s too hard.” But I knew I was effectively stuck with him. Then I was in France, doing pre-production stuff and the word came through that I was to go and see Miles in New York. Now, this is a long story, but a good story!

So, they bought me a ticket and the day before I was due to leave, “Ah, no, no, no, Miles will be in Los Angeles.” So they bought me another ticket from New York to Los Angeles and I flew to New York and then to Los Angeles and then I received a fax: “Hire a car, drive to here, turn left and park next to the red Ferrari.” I hire the car, drive to where I was meant to drive, but couldn’t see a red Ferrari. However, there was a four-wheel drive vehicle with the licence plate “Trumpet,” so I knew I was in the right place. So, I knocked on the door and a bloke answered and I was led in. Miles was painting and on the phone simultaneously. He wasn’t much looking at what he was painting but was more concentrated on being on the phone, which was quite funny. I waited and sat down, and eventually, Miles finished his call, stopped painting, came over to me and said “G’day.” We began to talk little pleasantries and every time I steered the conversation towards the film, he would steer it away. [He was] wanting to talk about the woman next door who had a block of land and wouldn’t sell it to him and I’m thinking “Come on, come on, we’ve got to talk about this film.”

I’m looking at this bloke because, I try to talk somebody and observe who they are. The bloke who led me in was called Mikey, who was some sort of employee, but treated somewhere between a man-servant and a slave. Miles would say “Mikey! Mikey! Get me an apple! Get me an apple!” And he’d say to me “You want an apple?” and I said “No thanks, it’s fine.” “No, he doesn’t want an apple Mikey, but I want an apple!” So Mikey would very carefully, get a little plate and get this apple and cut it into quarters, take the core out, put the four quarters on a plate, and bring it to Miles.

Miles would start eating this quarter of an apple, but he didn’t like the skin, so he’d take some bits of the apple and push the skin out of his mouth, so that it dribbled down the front of his chest and onto his lap. And I was thinking: “Oh my God! What are we going to do?” And then Miles tried to get a tissue out of a tissue box next to him and his hand was frozen in this claw and he couldn’t manage it and he ended up pulling about sixty tissues and they ended up everywhere, and there was this catastrophic scene of tissues and apple peel and I’m thinking: “My God, this bloke has got to come out to the desert and make a film!” — I was really concerned.

The one thing that Miles did say – which turned out to be very smart — was: “I want to work with Michel Legrand. Michel and I have worked before together and I want to do this with Michel.” Which was a big shock for me because suddenly there’s an extra $100-200,000 in the budget which we don’t have. But Miles said that was what he wanted to do, because he was going to do the music and act in it. So, if Miles says he wants Michel Legrand, you can’t say no. But that was about the only thing he said and the only conversation he allowed about the film.

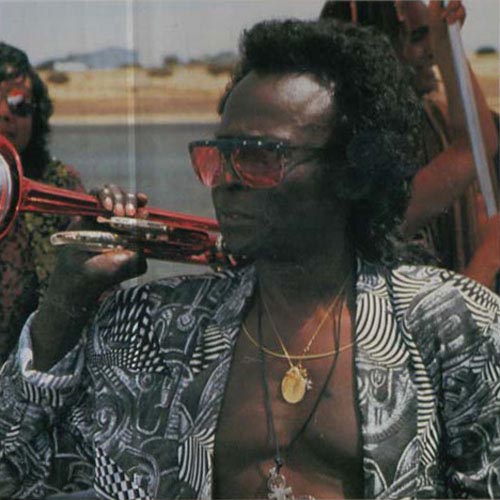

Miles © and courtesy Vertigo Productions

After about forty-five minutes, he called a halt to the whole procedure and said that was it. I thought: “Fuck! I’ve flown all this way, he’s got to be joking — we haven’t talked anything about the film.” So there were some protestations from me and in the end he said — and this was a Friday afternoon — “okay, ring me on Monday and we’ll have dinner or something.” I thought “That’s good, that’s better, okay, fine.” So I left, changed my tickets, because I was meant to fly back a couple of days later, and so now had to stay longer. Then I thought “I have to go back to Sydney after this,” so I changed my ticket so that instead of flying all the way back though New York, Paris, Zagreb, Dubai, Singapore, Sydney, I’ll go straight Los Angeles to Sydney. Bought a ticket for Sydney — they wouldn’t cash-in any of the other tickets, because they were dodgy tickets from Yugoslav Airlines — and rang Miles as appointed on the Monday.

So I said “Hello Miles.” And he said: “Oh sorry man, I’m just packing up.” I said: “What?!” “Yeah, I’m just packing up to go to New York.” I said: “When are you going to New York?” And he said: “In about an hour.” I said: “Miles, I’ve travelled half way around the world to speak to you.” And he said: “I guess I’ll see you in New York then!” Then he hung up the phone. So I got the tickets I’d thrown away back out of the bin, cashed in my Los Angeles to Sydney flight and the following morning, got a flight to New York. By this time, I was running out of money and I’m not fantastic in America at this stage. I’ve got a heavy suitcase, because it’s full of paperwork and schedules and I have no where in New York to go. So I land at the airport and think “I’d better ring Miles.” But I couldn’t even get the phone to work because American phone systems didn’t work as simply as Australian ones. So I’m thinking: “What the fuck do I do?” I’ve got $52, so I go outside and it’s snowing and I’m from Australia and completely unprepared to be there.

So I go to a taxi and I don’t even know where I’m going — I don’t even know what New York is. I looked at the phone book and there things like Queens and Bronx and Manhattan and they all looked familiar, but where was I meant to go? So I said to the taxi driver: “How much to go the main drag in New York?” He said about 40 bucks, so I dragged the suitcase in the boot and got in the cab. I asked to be taken to a cafe on the main drag. I thought I’d go to a cafe [and] have a coffee. There were some people I was going to try and stay with, but hadn’t been able to contact them, so I thought I’d go to a cafe, make calls and try and contact Miles. Half way into the city, I’m thinking “No, this is stupid. I’ll go to a hotel, I’ve got a credit card and I’ll make sure there’s a phone in the hotel. That’s the only sensible thing to do.” I said to the taxi driver: “Take me to a cheap hotel. All I need is a bed and phone.” [He says] “Yeah, yeah, no worries” So he drives into this demolition site. There is shit and garbage all over the place, bricks piled high. I’m thinking: “What the fuck?!” So while I’m trying to understand where I am, there’s a black Cossack, who comes out of the building site. He’s got the whole fur cap on, the long grey coat and the boots, and he takes my suitcase out of the boot and disappears into the demolition site.

So I’m trying to pay the taxi driver and run after this disappearing Cossack. It’s dark by now and I’m trying to find my way around and suddenly, there’s this hoarding and behind it is an escalator and I’m thinking “What the hell?” So I go up this escalator and it’s the New Holiday Inn. It’s not finished yet, but it’s open for trial customers. So okay, I eventually I see my suitcase and few other Cossacks around, so I know I’m in the right place. I say “I’d like a room.” And they say, “Okay that will be $200.” And I just lost it: “I said TWO HUNDRED DOLLARS! YOU’RE JOKING! Taxi driver said it was a cheap hotel and it’s a demolition site!” Everything was going wrong and then somebody said they’d give me a discount and it was down to $149. So I gave them my credit card and they gave it back to me and said: “Sorry sir, it’s not working.” There was a very sympathetic person and they gave me the room. They believed my story and I said I’d sort out my credit card. I got to the room and rang Miles and I got through and it was Miles who answered!

I said “Miles! Miles!” And he said, “You’re in New York?” I said, “Yeah, yeah, I’m in New York.” I said: “When can I see you?” It’s now Tuesday evening and I’m scheduled to fly back to France on Thursday evening. So Miles says: “When are you leaving?” I said: “My flight’s at 6.30pm on Thursday night.” He says: “Right, right. We’ll get together.” I said: “Yeah great, great.” He said: “Let’s together at [pause] Thursday afternoon. ” I said:”Yeah?” He said: “Yeah, three o’clock, no, no, no, let’s make it four o’clock.” And I thought “You fucking bastard! You know exactly what you’re doing.” So I said “Okay Miles, see on Thursday afternoon,” and I hung up the phone. I thought “Jesus, what do I do? I’m in deep shit, I’ve got no money, no credit, what do I do?”

Anyway, I ring Hillard Elkins in Los Angeles and he gives me the number of Miles’s [road] manager, Gordon Meltzer. So I ring Gordon and he says, “No worries, come around to the office tomorrow.” I said: “The office? Where’s the office?” It was six blocks away and I thought I can walk, because I only had $12 left. I had just enough money to scrounge a dinner and a breakfast and I wandered off to Shukat and Hafer [the offices of Miles’s manager and attorney] and they wanted to hear the whole story. And they’re laughing and every now and again, they’d say: “Did he call you a white motherfucker?” And I’d say “No,” and they said: “Oh he loves you! He loves you!” Anyway, Gordon said “You’re doing okay, you’re doing fine.” He said, “look it will be fine, I’ll be there. We’ve got to have his hairdresser — I thought “There’s another $20,000 bucks on the budget” — but I thought, “Okay, this feels more real.” And I never saw Miles again until he got off the plane at Meekatharra airport. It’s not a big place in the Outback. In the meantime, the music for the first sections had been done – all the stuff that we needed to be done live in the film was done. I had communicated with Michel Legrand and he had sorted all that out.

Colin Friels, Rolf and Miles on set © and courtesy Vertigo Productions

TLM: Whom did Miles turn up with?

RDH: There were four people: Miles, Gordon, Mikey and his hairdresser. That’s a security thing. It made him comfortable and he was comfortable.

TLM: What was Miles like on the set?

RDH: Miles was cautious. Australian film crews are reasonably respectful, but they’re really only respectful when you do your job in the way that it’s meant to be done. So there’s none of this “Mr Davis sir” stuff. Whereas the French crew, it’s “Mr Davis” and get on your knees and bow down. He was a bit sort of suspicious of that to begin with, and for the first couple of days, he was pretty cautious and pretty careful. But after that he was a joy to work with — he was terrific. He was cooperative, easy, friendly.

TLM:What was he like to direct as an actor?

RDH: With dialogue, he had a strange relationship with it. It depended on how he was and what the dialogue was. There were times when he just nailed it absolutely, and there were times when he just talked drivel. There are whole long scenes, which he did in one take, and there are other scenes which are chopped about because we had to salvage something from the drivel he was coming out with. But you knew they were salvageable — you knew there was stuff there. In a lot of ways, he was a pleasure to direct, because he listened and he took stuff on board, and he tried and he worked hard. He was dedicated and never caused problems — not once.

We were shooting the stuff in Paris where John Anderson wakes up looking for the bathroom and wanders around and finds Miles in the music room and Miles is tinkling on the keyboard. And Gordon Meltzer came up to me and said: “Look, you don’t know what you’re doing – I have never seen Miles like this. This is the most cooperative I have ever seen him.” It had very quickly become a situation where I trusted him and he trusted me. When actors do a film, there’s a lot of waiting. It’s shocking stuff and I don’t know how actors ever do a film. All I had to say was “Miles, I can’t afford for you to go to your caravan today.” “Okay man, I understand.” And he just sat there patiently waiting and then it would be his part and he’d do it and try and do it as quickly as possible because he knew we had to get so much done that day. He was great.

In this whole process, I had one astonishing bit of luck. The very first thing we shot with Miles was a playback thing. Now, Miles’s inclination was always to improvise, because that’s who he was. But when you’re doing playback you’re meant to playback what you’ve recorded and he couldn’t. And there was no sync [synchronisation track]. So this was a real problem. We had a trumpet tutor for Colin Friels. He’s a Western Australian trumpet tutor and a great bloke. He said: “Look, I think I have a solution to this trumpet problem with Miles. Miles is a great sight reader, so if I transcribe everything that’s he done and we stick the music just out of shot, then he can play the music and he’ll get it right.” So he transcribed the music and so we had the sheet music. Now for my sake — because I don’t read music — he’s written on the music where things are meant to happen.

So you have the final concert scene where Dingo is invited up on stage and then Billy Cross joins them [the jam session]. The sheet music has got things written on it like “Dingo starts to play,” “Billy Cross joins them” and so on. I’m talking to Miles and we’ve got this scene to shoot and it’s a shit fight [struggle] because we’ve got so much to shoot in one day and we’re going to be kicked out of this location. I say to Miles: “I really need you today. Please, don’t go your caravan. If you can sit just off-stage here, because we’re going to shoot this in such a way that it’s all chopped up. So we’ll have a shot here and here and here and then we’ll pull you on, sit you down and show you bits I want you to play.” Miles says “Okay, okay.” So I then said, “Let’s just see what you’re supposed to be doing.” And I’m holding up the sheet music and running my fingers along the music, “So, da dah starts here and Dingo starts.” So I’m running my fingers along the music, but I’m looking at the words that have been written by the trumpet tutor. And Miles doesn’t see the words — he’s only seen the music. So here am I — I can read music faster than he can! And he looked up at me and said: “Fuck man! You can do everything!” I worked out what it was and I thought: “Say, nothing, say nothing,” because from that point, there was nothing I couldn’t ask Miles to do. He was terrific all the way through. Attentive, on time, unproblematic – a joy to work with.

When we had some dialogue post-syncing to do some months after, I went to America to talk to Michel [Legrand] about the rest of the music and post-sync Miles. Miles kept not turning up to the post-sync sessions and it turned out that he was just scared. After about third cancelled session, I found him and took him through it and he did it. And he was just beside himself with pleasure. He said: “Fuck man! With you, I could do Shakespeare!” He thoroughly enjoyed having achieved something that he didn’t think he could do. And at that point, we began talking about doing another film together, which wouldn’t have had anything to do with music, because as an actor, he had this great presence. It was going to be a Louisiana bayou type movie; Miles in a rocking chair on the porch of a clapboard house on the edge of the swamp. He was going to undo his hair weave and be a poor black man, but of course, he died.

Colin Friels and Miles

TLM: There seemed to be a very good chemistry between Miles and Colin Friels.

RDH: They got on well together – they had enormous respect for each other, because they each had skills that the other needed — Colin was an actor and Miles was a trumpet player. They talked a lot and worked well together.

TLM: Regarding the script. Two things really hit when I saw the film. The first was the reference to Billy Cross having a stroke – and Miles had had one in early 1982. The other was the time when Billy Cross says to Dingo that he stopped playing because he didn’t want to be a museum piece — which was something that Miles was always determined not to be — someone from the past.

RDH: It’s extraordinary – that stuff was written by Marc before there was any thought of Miles playing it. The script was finished before Miles played the part.

TLM: I gather there was a problem with some early footage being destroyed at the processing lab?

RDH: In the Meekatharra stuff, when the plane lands, there was quite a bit of it destroyed in the lab. Of course, there was no way of going back and shooting it. It was like a two-day turnaround before we got word about the rushes. We got word about the problem in the last few hours that we had the airplane. We didn’t know what was missing, so I just had to shoot anything that might be missing. I remember that the plane had to take off from Meekatharra and fly to Perth because it had a freight run. We were just shooting and wouldn’t get off the plane. The captain is saying: “Look, I have to take off — I have to go.” And we’re like “Yeah, just another minute, another five minutes.” And in the end, the captain was screaming at us: “GET OFF MY FUCKING PLANE!” We just had to shoot as much as we could.

TLM: What was destroyed, did it affect the film?

RDH: It’s cobbled together. It’s not as good as if the original footage had been there, but it’s okay, it’s there.

TLM: Generally, what was the shoot like?

RDH: The conditions were difficult. The Outback town we ended up shooting — Sandstone – was so remote that it was two hours drive along a dirt road to the nearest anything. We go to this town and it has twenty-seven residents. So suddenly the crew come into this town of twenty-seven, although by the time we left, there were only twenty-six, because one of the residents died as a result of drinking with the crew and falling off his bar stool and hitting his head.

There were all these weird things going on like that. When we were shooting at Meekatharra, word had gone round that we needed extras and for days this stuff was in the news, because from 200 kilometres away, two people had started to walk to Meekatharra to be extras in the film and they got lost and one of them died. It was such a bizarre shoot, because we had French crew and Australian crew and the French work differently from the Australians.

At the airport scene there are some Aboriginal extras and they’re meant to have some connection with Miles. I turned up in the morning to shoot that stuff and I made a comment: “Gee, the Aboriginals aren’t very black are they?” It was just an observation. And so we shoot. What I didn’t know was, that behind my back, the French first [director] had got onto the radio and said: “The director doesn’t like the Aboriginal extras,” and this whole sequence of events took place that I no idea about that ended up costing this astronomical amount of money, because they rang Perth — which was 800 kilometres away — contacted a casting agent and said: “We need some black extras, real proper ones.” So they were galvanized into action and found us this minibus of black extras that we couldn’t use, because we’d already shot with the other ones – you couldn’t just add them in the middle. Late that evening, they got these Aboriginals extras, hired a minibus, hired a driver, and overnight, drove like fuck over 800 kilometres to get it there on time.

The poor Aboriginal extras — there was no accommodation anywhere. So some crew had move out of their hotel rooms. So the extras turn up — about half a dozen of them – on set, just in time and they’re completely fucked. And I say: “I can’t put them in the shot.” So, they get taken back to the hotel room. They borrow the minibus, because they don’t like hotel rooms — they don’t like to be constricted. So they took the minibus into the bush and completely trashed it. It cost just an astonishing amount of money because of this one comment I made. I think we had twenty rental vehicles all together and only one went back with less than $500 of damage because we were going along the dirt road. Three of them were complete write-offs from hitting kangaroos; people were off to hospital for surgery because the car has rolled or somebody had run into a telegraph pole. It was very difficult.

TLM: What was Miles like when he saw the film?

RDH: He was very funny. He got his brother and a couple of other people to come and watch it with him. He sat in the back corner of the theatrette, with a jacket over his head. And he’d occasionally glance over the top of it and when he saw himself, he’d pull the jacket back over his head. By the time we were half way through, he was mostly looking over the top of the jacket, and by the last quarter, he was just looking at the film. It was very funny! He liked it. I can’t remember what he said, but he liked it. He so enjoyed doing the film. He was really sad when it was over. I remember the last scene we shot, where he’s talking to Dingo and saying “Maybe you should go back to Australia and be yourself.” And they’re walking along the side of the Seine and he just wanted to keep shooting. He was so sad when it ended and I think it shows in his performance, because he allowed himself to be himself in a way that he almost never was. He trusted those around him sufficiently that he wouldn’t regret just being himself, which was probably a much nicer person than many people had come across.

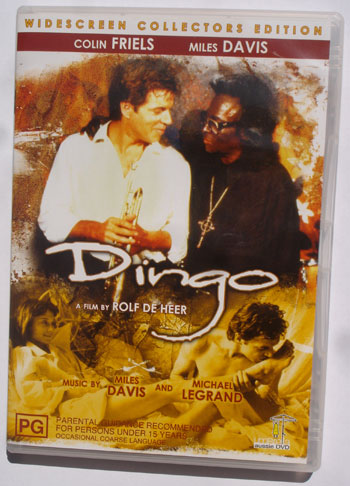

TLM: Why is the Dingo DVD impossible to find in Europe?

RDH: It was a French/Australian co-production and the French had the rights to Europe and the Australians had the rights to everywhere else. Every French company that was involved with it either went broke or got taken over and so the European rights are a mess. You would spend a couple of hundred thousand dollars just sorting it out for no return, so no one’s going to do it.

TLM: Looking back at Dingo, what are your thoughts?

RDH: It was a very difficult shoot generally, but two aspects shone through. One was the stuff that was shot in a really remote place with just a small crew. And the other was the stuff that was shot with Miles, especially the last scene in the club, which seemed so impossible in terms of what we had to achieve and how many shots we had to do. Everybody was so cooperative and somehow we got it done. It was just an extraordinary day’s shoot. You always think of things that could have been done better, but I’m proud of that film.

Many thanks to Rolf for his time. Check out Vertigo Productions, Rolf’s production company’s website, which contains some very interesting production notes on Dingo. These include unused liner notes written by Rolf for the Dingo soundtrack album, with track-by-track descriptions.

Dingo can be purchased on DVD or Blu-ray from Amazon UK and Amazon US