John “Tokes” Potoker is a multi-talented sound specialist, whose engineering, mixing, remixing and production work can be found on a vast array of recordings. John has worked with many major artists and producers including, Paul McCartney, Phil Collins, Genesis, Steely Dan, Peter Gabriel, Brian Eno, Quincy Jones, Hugh Padgham, Phil Ramone, Talking Heads, Scritti Politti and New Order. He also worked on a remix of the Miles Davis tune “Shout,” a disco-funk track from the album The Man With The Horn. In this exclusive interview, John talks about how he got into the music industry, describes what it’s like working with some major artists and producers, and provides many great insights into the art of producing, engineering and remixing.

John Potoker – photo by April Rivera. © John Potoker

TheLastMiles.com: Can you tell us a little about your background?

John Potoker: I was born in Queens, New York. My Dad was a musician – he used to play piano with the Tommy Dorsey band. My Mum was an ice skater. Dad starting playing on the New York studio scene and he got a gig at the WOR-TV station, on the Ted Steel show, which was like a Johnny Carson show. We moved to New Jersey when I was about three, and that’s where I grew up.

TLM: Where you always interested in music?

JP: Being a kid of a musician, I grew up playing piano and guitar. I was really interested in recording, because, when I was aged around nine, I would go to the studio with my Dad when he was doing some jingles work. I’d watch him work from the control room and I was fascinated by what was going on.

TLM: So have you always wanted to be on the other side of the glass?

JP: This is how the other side happened. A friend of mine was in New York recording a demo and asked me to come in and play guitar on it. It was at A1 Sound, a studio owned by Herb Abramson, one of the founders of Atlantic Records. I did my part and then hung out in the control room watching the rest of the session. I got talking to Herb and he saw that I was interested in the recording process, and I told him I’d like to come by some time. Later on, he called me and told me he had an engineer who was taking a vacation and they were going to try and get me up to speed – I was probably aged around seventeen or eighteen. The engineer was Steve Rosenthal, he now owns The Magic Shop [studio] in New York – he’s a well known engineer. So, he was away and I got to do a couple of sessions. When Steve came back, he did his thing and I got to do my thing. But I left soon after. As a young guy, I didn’t stay in any studio for too long; I was always moving to new studios.

TLM: Was it a steep learning curve or did you find that the technology and the techniques of recording came naturally?

JP: They came pretty naturally, because when I was a kid, my Dad had a 2-track reel- to-reel recorder that he would put stuff on and I would play around with it. Even though it was only 2-channel, I could still do things like sel -sync, a way of selectively using some of the record head as a playback head so I could record new signals to other tracks in sync with the existing tracks. Later I did take a course at Plaza Sound, a studio inside Radio City Music Hall and basically I learned recording on a 16-track multi-track from engineer Rob Freeman. I also learned about micing techniques. That was really my education; the rest of it was learning from experimentation, reading whatever tech manuals I could find, and being in the studio and picking stuff up from whoever I was around. I ended up working at various places including a jingle house called Premier Sound, which was on 57th street – it was in the Arista building. With jingle work, it was so quick and every session was different – it was a great place to learn. I assisted there for a while, and at night, I would cut demos and be working on songs with some of the other engineers. One of the engineers was the son of the owner [of Premier Sound] and we hit it off and starting writing and producing together. We’d bring in local bands and friends and record them.

TLM: Do you need to have a musician’s background to do the sorts of things you do – engineering, production, mixing, remixing?

JP: I think it’s really helpful. But if you’re a producer, it’s still a very wide word. Certainly, there are producers out there who are really successful and who don’t have a musical background and don’t know that much technically. But they are a really good people person. They know who to call and how to work with people. That’s a huge part of the job – working with people and making them feel comfortable and creating a great atmosphere. Knowing when something is going well and when it’s not, and what to do when it’s not. It depends on the type of producer or engineer you are. If you’re a scoring engineer, it would be great to be able to read the score!

TLM: What other qualities are essential for being a good producer?

JP: Empathy It’s really like a shared vibration; you need to be in a creative atmosphere and you need to understand the person you are working with, and sometimes that takes a little getting used to. Some people are quicker at adapting. It’s important to hang with people. If you are really into producing, you need to find out what that artist is trying to say and you need to establish a common language. You have to be able to interpret things for other people, because they may not be that great at communicating what they want; they might not have the language.

TLM: And what makes a good recording engineer?

JP: Technical skills matter, but so does having a listening attitude. Knowing what microphones to use and where to place them. With mic placement and the room environment, just making little adjustments here and there can make a great difference to the sound. Know the sound of your mic preamps and compressors. Be able to react quickly to what you’re hearing. Have a really deep ear and be able to listen into the details of things; sometimes just changing a cable out will make a big difference. If a musician or artist is in the moment everything else is secondary you need to capture their performance. Always be in record. The trick is to capture their performance and do it in a way that is sonically pleasing and inconspicuous, and sometimes you don’t get a lot of time to do that. I think engineering takes imaginative skill, you need to have within yourself some sort of sonic reference and you have to have some experience and the readiness to find a solution if a thing is not sounding right.

TLM: What about remixing?

JP: That’s really just listening to what that production, recording or song is saying. All that stuff is there. A lot of the times with remixes, people would just present the tape but it would tell the story – it tells you where to go. It takes imagination. For me it wasn’t about knowing what the original version of that was – I wouldn’t necessarily want to listen to it that much. Sometimes, I would never even hear it; they would send the single or album version over just as a reference. But generally, for me, I didn’t want to know too much about where they went with it, because they were looking for something different. It’s about mining the gold that’s on there. For example, the remix I did for Phil Collins’ and Philip Bailey’s “Easy Lover”. Phil had used a drum machine track as a guide track, instead of a click track when they were putting the song together, and that never went to their version of the song. But when I got the tracks, the drum machine was still there, and out of that drum machine, I created a part to lead in and out of areas of the remix. It’s about finding things and utilising them in a different way that brings it to a different version.

TLM: Are there any producers, engineers, remixers who have influenced you or whom admire?

JP: I did most of my remix stuff at Sigma Sound Studios in New York. There was a great camaraderie between the various producers and engineers that were working at the studio. You would pop your head in [a recording session] and hear something that inspired you. It was never so much about listening to anything that was complete – it was work in progress. But everybody had different ideas and different techniques and different rooms, different instruments, different mics. There was a keen sense of competition, not against anything, but in doing great work.

TLM: Let’s talk about some of the artists you’ve worked with. You worked with Steely Dan on the Gaucho album.

JP: That was interesting! It was situation where I was working at Sigma and they [Donald Fagen and Walter Becker] had come in and were working with another engineer, Jim Dougherty They would also bring in Roger Nichols – he was their main engineer. Jim and I were both engineers, but when Steely Dan came in, we would assist with those sessions. Jim was from Philly [Philadelphia] and had to get back there for a couple of days or so. I got the call: can you work with Steely Dan? I was like: “Of course! Are you kidding?!”

Sigma people were used to popping their head around doors but Steely Dan was a closed session. Our duties were to set up machines. At that time, we had 24 track machines and you needed to calibrate tones and make sure everything was set for record and playback, and of course, Steely Dan was a stickler for that; you had to calibrate those machines every session and set-up microphones and make sure everything was ready to go. I had watched Jim do that when they weren’t around so I kind of knew what they were looking for. I got to hang out with them for a good while; it was just incredible.

Donald Fagen and Walter Becker © steelydan.com

We didn’t get a lot of work done, because they worked really slowly, but I got to cut some vocals with Donald Fagen, which was great; we did some piano overdubs and we did some bass stuff with Walter Becker, which was really incredible. We got a good portion of a bass part and that was really different, because, with all the other overdubs we were working on – vocals, piano or whatever it happened to be – if it wasn’t happening, it wasn’t happening, and it never seemed like we were making a lot of headway. But with the bass part for some reason, we clicked into a groove and they were keeping the parts that we were recording, which was exciting. You could tell – the whole energy in the room changed – something’s happening!

Roger Nichols was an amazing engineer. Steely Dan was a band that kept a lot of things and later on, would decide what they wanted to do with them. When I started working with them, there was very little to do, but as they got more comfortable with me, there was way more to do. Part of that was doing some drops [drop-ins], because Roger had a lot of moves to make at the board. With Steely Dan, it was like: “We have a vocal we like, so let’s go to another track and another and another,” and maybe there are three or four vocal tracks of the verse, but they only like the beginning of track 1, and they like a word of Track 2, and bars 5 and 6 of track 7. Well, Roger would have to be making all those moves as they are recording and drop in and operate the tape machine. I ended up running the tape machines and doing the drops while Roger was operating the switches at the [console] board. And that’s how we got a groove going so well when Becker was doing a bass overdub – things started moving. And it’s kind of on the second engineer, because if he’s running the tape machine, he’s running the tempo of the session, and that session started going a lot faster than it normally would!

TLM: How did you get to work with Paul McCartney on “Spies Like Us” ?

JP: I had done remixes for Phil Collins so I knew [producer] Hugh Padgham and I had worked with [producer] Phil Ramone on a Julian Lennon record [“Stick Around”]. Hugh and Phil were working with Paul on a track and they called me. Phil said: “We want you to do a remix,” and I said: “Excellent – I’m down for that!” And then Phil said: “Paul’s going to give you call,” and I was like: “Fantastic!” The funny thing is, at that time, I was freelancing and doing a lot of work in various studios – England, Paris, New York, Nashville, LA, Toronto, wherever. I happened to be at my parents’ house in New Jersey, where I used to listen to The Beatles as a kid. Beatles records where always on the Christmas list – I was total fan. It was really surreal; I didn’t know when Paul was going to call and I happened to pick up the phone and there was this voice: “Is John there?” I was like “Yeah.” “Well, Paul here…” and so we just started talking about the track. I usually talk about what sections of the song I find interesting, or where I might put a breakdown or double up choruses. I had ideas and he had ideas about the instrumentation and it was just great – amazing. I went in and did it. One of the remixes was used at the end credits of the film.

TLM: And Phil Collins?

JP: Phil is just a great guy. When I worked for Virgin [Records] I ended working a lot at their Shepherd’s Bush Townhouse Studios. That’s where Phil did a lot of his work and Peter Gabriel did his stuff there too. I had been working with a fellah called Barney [renowned producer/engineer Steve “Barney” Chase] and whenever Phil Collins or Hugh Padgham would come in, Barney would assist. He had been working with me on a few things and then he said he was leaving because Phil Collins was coming in. The first thing I did for Phil was the “Easy Lover” remix. Townhouse also had a kitchen which provided food, which was great, because people would be working around the clock there. I remember coming back from lunch one day and Phil was in the hallway and he said: “Hey John, I want to talk with you about something.” Then he played me the track and said he needed a12-inch [single version] and that Barney had told him that I do a lot of remixing. He said: “But I need this right away,” and I thought: “What does ‘right away’ mean?” This was probably a Thursday and he said, “I need it by Monday.”

That weekend, he was recording drums on the song for Band-Aid [“Do They Know It’s Christmas”]. And that whole weekend, I worked on “Easy Lover”. I remember working all the way through Sunday night getting the remix ready for Monday morning and Phil showed up about 10 o’clock. I said: “If you hang on a little bit, I’ll have it finished – I was making some arrangement edits putting in the last couple of pieces. They went and had breakfast and Hugh, Phil and [guitarist] Daryl Struermer came in the control room and I played it down. When the song started, it began with the drum machine I was telling you about earlier, and Phil was sitting next to me and he whispered: “If I had thought of that intro, I would have used it on my version,” so I thought: “Okay, I guess he likes it!” I ended up doing quite a few remixes for Phil – “Sussudio,”, “Take Me Home” and others, and then I ended up doing some stuff for Genesis.

TLM: And there’s another Genesis connection with Peter Gabriel’s “Sledgehammer” remix

JP: That was a different conversation. Peter Gabriel sent me the tapes and we got to speak on the phone. It was interesting when I started talking about the sections and what I wanted to do with the song. I didn’t seem like Peter knew the song in the form that I was talking about – I mean what had been sent to me: intro, verse, chorus, re-intro, verse, chorus, bridge or whatever the structure was. Instead of it being a detail-orientated discussion, it was more feel-orientated. I was unsure of how clearly I articulated my ideas and communicated with him on the phone. He obviously liked what I did because he called to tell me he was shooting a video for the song and he had a part of my mix cut into the video version of it. I found out later on that the way Peter would write a song on the “SO” album was that he and the band would do lots of different jams and he would assemble the song from the jams. It wasn’t like a Paul McCartney, who might go in and write the song on a piano or guitar and have the structure and have the song basically together. Peter and his band would go in and experiment and jam, pick the bits and create a song structure. “Sledgehammer” was probably so new and fresh to Peter that he hadn’t committed to how the song structure went. I remember some friends had worked on some Yes records and they told me that’s how they put together a lot of their material – it was pieced together later on.

TLM: You also worked with Talking Heads David Byrne, who is interesting musically, as well as being highly focused and knowing what he wants.

JP: That was great. They came into Sigma with [producer Brian] Eno and [engineer] Dave Jerden. They had been recording in the Bahamas for a long time. It was that same thing; whenever a visiting engineer came into Sigma, I got a call to work with them. I worked with Dave for a couple of weeks, but Dave had been working on the record for so long that he needed to get off it and come back to LA and work on another record he was committed to. Fortunately, I had impressed them enough and so Eno and David asked me stay on and work on the rest of the record, which was fantastic. At the end, David Byrne went to LA to mix the record with Dave, and Brian Eno and I stayed in New York and worked on the rest. So it was really interesting: half of it got mixed on the East Coast and half on the West Coast.

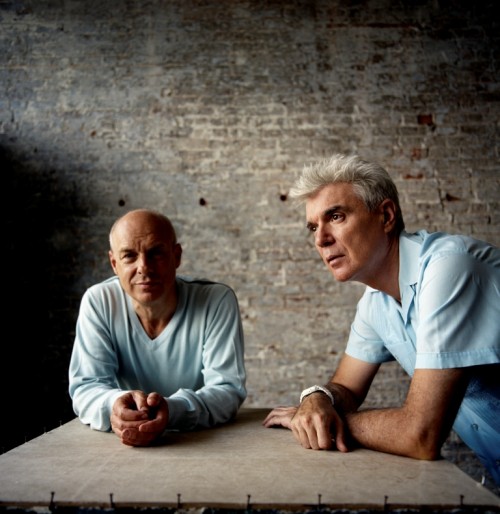

Brian Eno and David Byrne © Danny Clinch

All the people I have worked with are my top people to work with, but working with Brian and David was a new approach; it was never like you needed to do the same thing again. With Steely Dan you needed to match things, so micing techniques and mic pres [preamps] had to be the same and everything had to be the same. With these guys, it was like: “Let’s try this today!” Whatever it might be, it could the most outrageous idea: “Instead of using what we were using for percussion yesterday, I’m going to bring in my pots and pans.” The thing about Brian Eno and David which was great was that, you might put a part down, but that part might not ever make it to the record. But that part was essential for getting you to the next part that was the great part that makes the record. You might play a guitar part and at the end of the day say: “Yes, that was good but I’m not inspired by it, so let’s try something else with it,” and you might end up re-recording it through a bunch of effects boxes and it morphs into something else.

And that’s how you leave it, until the next morning, you come back play that through and start pulling things out of the mix and only feature that and two other instruments, and then do another overdub on top and then wow! That’s fantastic! And then you erase the two other things that got you to where you are. They were not afraid of getting rid of things, which was different for me, because most people want to keep everything and decide later on. But Brian Eno has his oblique strategies and uses them in the studio. If things weren’t working in the studio, he’d resort to an oblique strategy and you’d have to adhere to it! It wasn’t often, but you’d do whatever you had to do. It was something else working with those fellahs.

TLM: D-Train?

JP: As a remix engineer I used to work a lot with DJs, including François Kevorkian [aka François K]. He also worked as A&R [artists and repertoire] for Prelude Records [D-Train’s record label]. Frankie and I became good friends and he came in with the D-Train record. and that was great. We overdubbed some synth parts and the bass line with Hubert Eaves. I think we even used my Sequential Circuites Pro One mono synth on it.

TLM: An interesting remix was New Order’s “Blue Monday”

JP: It’s funny, because I forget how many fans New Order has, and who those fans are. For example, [producer/composer/audio specialist] “BT” Brian Transeau is a really talented younger guy. We got to talking one day and I went see how his studio was set up, because I love his work, and he was telling me: “Yeah man! That New Order stuff, it’s amazing!” I worked through Quincy Jones on that, because his record label Qwest had New Order [on its roster] in the States. Quincy came by that session and I did keyboard overdubs with a player called Robbie Buchanan. Robbie and Quincy knew each other. I got to hang with Q and talk about the track, and that was just a thrill – to be in the presence of Q was just incredible.

TLM: Any other memorable remixes?

JP: “Sussudio” was a great remix for me, because later on, I moved from New York to LA and Phil came by when he was touring with his band. He was playing arenas and he said: ‘We’re doing your arrangement of “Sussudio” in my live show,” and that was quite a compliment.

TLM: Can you take us through the process of remixing?

JP: I always did remixes as quickly as I could. It depended on who I was working with – Frankie [François Kevorkian] and I would work through the night. If it was a single session, it was a good 12-14 hours session. If we had the luxury of coming back the next day to listen, we might tweak it. Most remixes were like a day to a day and half situation. With Jellybean [John Benitez] we would work 8 hours day sessions. Generally, with remixes, there’s also some deadline or a budget that you’ve got to deal with. You’ve got a specific amount of time and money to be creative with and you just got to get into the mode of understanding what you have to do and turn it on. There would be method to how I worked. Probably, for the first two or three hours, I would get a song up and balanced without any automation. Then if needed maybe we would overdub some percussion or synth. Most of the remixes I did were on an automated console. I would get the whole basic song to the place where I wanted it sonically and then we would go and work sections of the song. Then I would re-automate over those sections and print them and edit it all together as I go. So, I would say at some point: “This is the start of the song, I’m going to take something from the outro and now make it the intro, and work on that. And work on these eight bars or sixteen bars or whatever. Sometimes, I wouldn’t be able to tell how the mix was going until I had those pieces working. Then, I might find that when I ‘m hitting the verse here, I need to cut the piano part sooner, because there’s no keyboard in the verse. You have to make the transitions work. It’s like you start putting the puzzle together, but when you put in another piece, it didn’t quite fit right or you didn’t have the right piece. There’s a lot of going backwards and forwards to make the music better. It’s how much can you perfect it and still get it done on time and budget. It’s always challenging and interesting.

TLM: Has remixing changed over the years?

JP: When I was remixing, I was adding components to what was there; now, nothing’s sacred: you can get rid of all the instrumentation and just use the vocals; you can change the chord structure, change the tempo and do things that are drastically different. A lot of times, I think it’s missing the mark. I don’t find too many remixes these days that I prefer to the original, where as the stuff I was working on, the remixing didn’t annihilate the song; there was something new to it.

TLM: Is there a danger of technology getting the way of the music these days?

JP: It depends on the type and style of music. If you’re talking about recording real musicians, there’s the tendency where you could do too much, but if it’s the kind of thing where you are dealing with samples and loops and MIDI, and just one person is recording that track, it affords you an amazing amount of detail. It depends on whoever is in charge of the session. It’s got to be somebody who won’t get lost in the forest and still have the overview to know when it’s too much. Most of the mixing I’m doing today is totally in the box [on computer] and it’s in Pro Tools. Pro Tools affords you the facility to go and get specific parts of automation. When I was mixing on SSLs [Solid State Logic mixing desks] or doing most of the remixes we’ve been talking about, the only things the automation was affecting was the fader mutes and fader volume rides of the individual tracks or the fade on the master fader -I was not automating pans, Eqs or effects . Those types of moves you had to perform live to the 2-track mixdown machine. There was no automation for micro-mixing. – now I can automate anything I want. It makes it better in the sense that I can get what I want to get, but you can also get so detailed that you miss the rawness or the overall feel of something that makes a particular mix really compelling. It’s not that you’ve got everything perfect, but that something is pushing or maybe coming in too loud that makes the mix impressive. It’s a fine line.

TLM: Where does remixing end and composition begin?

JP: It didn’t on the stuff I worked on. Nowadays, I can see where people are really changing up the song maybe just keeping the lyric. They may even be changing vocal melody. If that’s going on, you have to consider whether you are rewriting the song. There are software programs where you can reposition the vocals and now have the singer sing different notes and duration; and change the melodic and harmonic content, so you’re kind of rewriting the song rather than remixing. For me, remixing was focusing the song in a different way and maybe adding a couple of elements, but not forgetting about what was there.

TLM: You also worked with Scritti Politti’s Provision album that had Miles Davis playing on it.

JP: That was wonderful. I ended up meeting the guys from Scritti – [keyboardist] David Gamson and [drummer] Fred Maher were from the States. [Singer] Green [Garside was from England. I had heard Scritti at the Townhouse. [Producer] Arif Mardin had worked on a bunch of their tracks and they were mastering some songs at the Townhouse. I got to hear some of that stuff and was blown away by it. I had Gemma Corfield at Virgin get in touch with David and I ended up recording some overdubs on some additional tracks. We did drum sampling, which was way before people got into sampling. My only encounter with sampling prior to Scritti was probably working with Eno on [his and David Byrne’s album] My Life in the Bush of Ghosts. I got to mix a couple of tracks [with Scritti Politti]including “Perfect Way” and then we came back to the States and I produced “Best Thing Ever” with David and Green at Minot Sound studio in White Plains, New York, where [Miles’s bassist/producer]Marcus Miller was working and I got to meet him. Later I mixed a few more things for Scritti at Sigma.

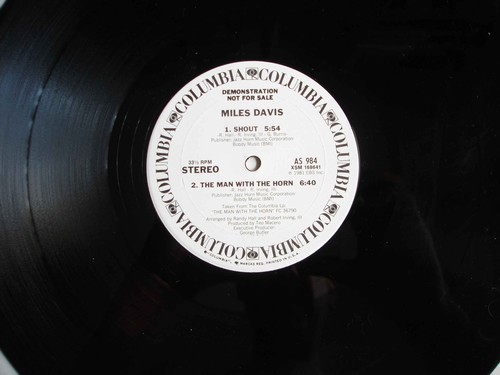

TLM: Finally, we get to talk about the “Shout” remix!

JP: It was in Studio 5, Sigma Sound Studios, New York City. That session was through Jimmy Simpson, the brother of Valerie Simpson [of Ashford and Simpson]. We did drum overdubs with Chris Parker on drums. In terms of mics, we most likely used a 47 fet [Neumann U47 fet ] in the bass drum; Neumann 87s on the toms and overheads, and an AKG 452 on the hi-hat. The snare would have a Shure [SM] 57 [on the] top and an AKG 452 on the bottom. Then, I probably stuck up a couple room mics. I didn’t get to talk to Miles. Jimmy more or less knew what he wanted to do with the structure of the remix, but when it came to the actual mix and putting it together, that was basically on me. Jimmy was involved in the final mastering and approval. He was the kind of producer who wouldn’t necessarily be there all of the time, so he would come in and check it. He might say: “I like that,” or “Let’s break it down further,” or “Can we bring that part up?” It was amazing to throw up those kinds of tracks and hear those kinds of musicians; it was incredible.

TLM: Last question: what are you doing today?

JP: Record mixing, some remixing and mastering, Live event sound supervision, recording and FOH sound, 5.1 [multi-channel sound] mixing and supervision for HD broadcast TV and film and mixing in Iosono (www.iosono-sound.com). It’s a new audio technology, holographic 3D sound, and it sounds incredible. I’m keeping busy!

Many thanks to John. John’s new website is going live soon. Check out:

www.johnpotoker.com