Saxophonist Eric Leeds began working with Prince in the mid-1980s, a period when Prince was arguably at his creative peak. It was certainly a very productive period that saw Prince [and Leeds] working with Miles on several music projects. In the first of a two-part interview, Eric talks about his background, what it was like working with Prince, his love of jazz, and in particular, the music of Miles Davis. Incidentally, Eric is the younger brother of Alan Leeds, who was Prince’s road manager during this period. You can also read Alan Leeds’s interview here on TheLastMiles.com

You can also read Part Two of this interview at TheLastMiles.com

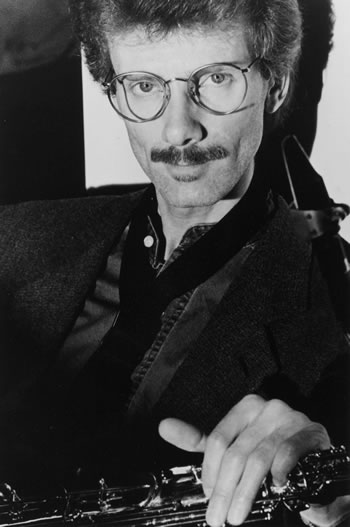

Eric Leeds – photo by Buckmaster © and courtesy Eric Leeds

TheLastMiles.com: Eric, can you give us some basic background on yourself please?

Eric Leeds: I was born in January 19 1952 in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, where I lived until I was seven years old. Then moved to Richmond, Virginia and lived there from 1959 to 1966. My father was a retailer so we moved around a bit. When I was fourteen, we moved to Pittsburgh, where I went to junior high school and college – I lived in Pittsburgh for eighteen years. That’s where my musical career started. I studied saxophone with Eric Kloss, a prodigy that came out of Pittsburgh. When he was sixteen, he was signed to Prestige Records and he had a string of successful hardcore jazz albums. He recorded with [drummer Jack] DeJohnette and [keyboardist Chick] Corea and [bassist] Dave Holland, Miles’s rhythm section. He recorded with Pat Martino and people of that calibre. It was a wonderful opportunity to have gotten to know him and study with him – he was my mentor.

TLM: What inspired you to take up the saxophone?

EL: Real simple. I’m a musician because of Ray Charles and I’m a saxophonist because of David “Fathead” Newman [who was in Charles’s band]. The music that I was introduced by my brother was very much R ‘n’ B. By the time I was eight or nine years old, I was immersed in Ray Charles because of Alan! That’s the music that turned my head around and for whatever reason I just gravitated to sound of the tenor sax of Fathead Newman. When I was about ten years old, I said ‘I want to try to do that.” I was also beginning to listen to jazz. I played alto at first because the tenor was too big for me physically, but by the time I was in high school then I started playing baritone really serious and that was my major instrument through college. I finally got to tenor, which was where I really wanted to be, although I still play baritone occasionally.

TLM: What were doing before the Prince gig?

EL: Growing up in Pittsburgh, I had my freelance [work], played a lot of jazz gigs, had my own band and then had a pretty successful funk R’n’B dance band called Takin’ Names. We also did very progressive jazz-fusion, Miles-orientated, Weather Report-orientated music in order to make a living. We tried to do different things, playing the dance clubs around Pittsburgh. This was like in the late 70s, which was really a great era to be able to that. If you were going to be a cover band doing funk stuff I don’t think you could do it in better times than that. We wrote quite a bit of our own material and in fact some of the stuff I wrote at the time ended up on recordings of mine fifteen, twenty years later!

TLM: How did you get the Prince gig?

EL: After playing bar band for around six-seven years straight I was kinda burned out. My trumpet player Matt Blistan [who played with Prince under the moniker of Atlanta Bliss] had moved to Atlanta, so a few months later I moved down and hung out with him. I wasn’t doing much in Atlanta, just bumming around and doing freelance stuff and trying to decide what I wanted to do next. By then, Alan was already working with Prince. This was 1984 and the group The Time broke up, and Prince was putting together a new project that he called The Family. And it was the first time he was seeking a saxophone player. Alan had already mentioned me to him and had given Prince a couple of cassettes of my playing on a variety of things. And Prince was intrigued enough [so] when he was putting this group together he told Alan ‘call your brother and see if he’s interested in flying up here and doing some recording.’ That’s how I got the intro.

TLM: Were you excited when you got the call?

EL: I was not a fan of Prince’s particularly – I was not really that much aware of his music. There were several songs that I had heard that I liked but I don’t think I owned any Prince albums at that time – he wasn’t really somebody who was on my radar screen other than the fact that Alan was working for him. And actually it took Alan a couple of weeks to convince me that it was something that I might be interested in!

So I finally decided: ‘This is silly. The worst thing that can happen is that I don’t like working with him or he doesn’t like working with me and I get a couple of session cheques out of it! So I really came up [to the gig] with pretty much a blank slate. Alan had already told me ‘regardless of what you think of the music or him, the guy’s a remarkable musician and if anything, you’ll relate to him on that basis.’ I was happy that I did enjoy the music we started working on, but more important than that, I did start to realise that this guy was something special. And that basically set the tone for my relationship with Prince. I’m not a Prince fanatic and there’s probably much more music that I’m really not that interested in than the music that I am. What was fulfilling for me for all the years and all the experiences that I’ve had with him is just what a remarkable musician is. And even if a particular song or project we were working on together wasn’t something that I was going to go home and listen to, it didn’t matter; it was being part of the process that was very interesting.

TLM: What was the first meeting like with Prince?

EL: I was preparing to work on some tracks that he had already done. I walked into a room [studio] and the first thing he said to me was ‘I can give you a cassette of the tracks to live with for a couple of days.’ He was kinda smiling and I smiled and said, ‘You know, I could do that, but I’ve got my horn. I’m here, you’re here; lets make some music.’ He kinda chuckled and said ‘okay’. I didn’t say that to impress him, it was just, you’re here, let’s go! I think he appreciated the fact that I was just ready to dive in and whatever was going to happen was going to happen.

TLM: Earlier you said that you realised that Prince was special. What makes him special?

EL: It’s just little things like the fact that he can be very spontaneous in the way that works in the studio and the way he approaches music, which I’ve always kind of related to someone of the jazz ethic. Prince is not a jazz musician in the traditional sense and certainly doesn’t have the harmonic background that we would associate with straight-up jazz musicians, [but] he can apply a sense of spontaneity, whether he’s in the studio or in rehearsal or in a life situation that is more true to the jazz ethic than a lot of jazz musicians that I’ve played with [laughs]! I always responded to that because that’s what I came out of.

It was interesting the times he would try and find ways to utilise what I could contribute to his music. Sometimes he could reach down inside of me and get things out of me that I ordinarily wouldn’t have done if just left to my own devices, which could add to my vocabulary as a musician. One time, he told me ‘look, I don’t want you to play this song like you know to play your instrument. I want you to approach this song like it’s the first day you ever picked up the saxophone.’ The first reaction was ‘I’ve got a sound that I spent twenty-five years developing!’ But then I thought ‘this is his way of saying what Miles used to tell [keyboardist] Herbie Hancock and [saxophonist] Wayne Shorter and [drummer] Tony [Williams] and [bassist] Ron Carter: ‘I pay you guys to practice on the bandstand. I don’t want you to play what you know – I want you to play what you don’t know.’ There were times when Prince would ask me to come into the studio and put a horn arrangement on a song and maybe it wasn’t a song that was particularly interesting to me and he would just leave the track with me and leave the studio. He’d leave instructions or he might say ‘here’s the song, do whatever you want with it.’ if it was a song that didn’t do much for me, that was a little troubling, because it was too easy to basically fall back on my own clichés and simply give him something that I thought would fit the bill.

But it was a different occasion when he would be there. Prince wasn’t there to satisfy me – he didn’t owe me anything as far as what he was doing. He had a sense of the kind of music I liked and didn’t like and sometimes he’d laugh and say ‘you need to play like a rock and roll player – do your best!’ Sometimes that would be cool with me because it would put me in a situation where I’d think ‘this isn’t really where I live, but yet I have to do something that will work in the context of what he’s looking for.’ And if he could get something out of me that I would not ordinarily do, then I could come away with having gotten something from that. Sometimes the rather unorthodox way that he would approach using the horn section that would be counter to everything I knew. Sometimes it would work and sometimes it wouldn’t and I would just think to myself, ‘this is just a bunch of crap.’ But sometimes, something would pop out and I’d think ‘this really works and it’s really different.’ Sometimes it does pay to have an open mind!

Also, the fact of the manner in which he worked in the studio and how would utilise the studio technology, as an instrument in itself, which helped develop my own confidence on how I could utilise that. By the time I was ready to go into the studio and work on my own music, I think the experience with Prince over the years had given me a leg-up in terms of coming in the studio with a piece of music and knowing where I wanted it to end up.

TLM: What was your relationship with Prince like from a musical point of view?

EL: Conceptually, as a musician, I was pretty much defined by the time I had met Prince. I can’t say from a specific standpoint that he is somebody who had influenced me and defined me before I had met him. I was already thirty-two years old when I met Prince, which put me substantially older than everybody else in the band at the time. I was the first ringer that came in; somebody that came in from the outside and already had a music career of his own. Whereas almost everybody else who had worked with Prince, came up with Prince.

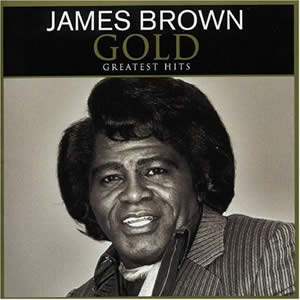

Another important fact was that I played an instrument that he did not play and, from the beginning, it gave me a much greater opportunity to define and develop my own role in his music than for any of the other people in his band. Prince looks at life as if it’s a movie. He’s the star, he’s the director, he’s the producer, he’s the scriptwriter, he’s the costume designer, he’s the special effects designer. Basically, he likes to put everybody he knows in a role in his movie and if you’re basically willing to allow yourself to be handled like that, fine. It kinda gave me an opportunity to develop my own character within his movie than I think it did for some of the other players in his bands. Plus I’d already known James Brown because of Alan’s association with him [Alan had been Brown’s road manager] – I’d known James Brown since I was fourteen – so having been around somebody like that, it kind of gave me more of a context of what it was going to be like when working with somebody like Prince. That worked for me for quite a long time until many years later that might have started to work against me! Prince and I have had our serious fallings in and out over the last ten years, which isn’t unique with anyone who has ever worked with him!

TLM: So working with Prince was both challenging and inspiring!

EL: Absolutely. It’s not a relationship that I had ever aspired to, but so much of what has happened in my career has happened because of my association with Prince. It’s not as likely that I would ever had known Miles and that goes for a lot of other musical relationships I’ve had. The visibility and the notoriety that being associated with Prince gave me and being able to build on that. You never know how your life would have turned out, but I certainly don’t regret anything of the relationship that I had with Prince.

TLM: How did Prince prepare his musicians for a new recording? Did you have charts for example?

EL: No. He does not read or write music. At the time I was in the band, myself and the trumpeter Matt Blistan were the only guys that read music. Basically, everybody else would play by ear. But Prince knows the difference between say, an E minor chord and an E major, but as far as reading musical notation, he doesn’t know how to do that. So basically, it would sometimes be a matter of him humming parts to me if there was a specific riff or lick. Or a lot of times he would look to me and say ‘is there anything you hear on this?’ Or if it was a solo he’d just open it up to me. You never knew specifically what the process would be on any given song until you started working on it. There were many times when he’d just leave a track in the studio with instructions for me to do something, but a lot of the times he’d give me a bunch of tracks and say ‘go in and do anything you hear on it.’ More often and not, he would not end up using a lot of the things I would do, but occasionally he might. The way I looked at it, is that if he ended up using something that I had contributed, fine. But if he didn’t, the worst of it was that it gave me an opportunity to just work in the studio.

You could not allow yourself to take any of this personally, whether he liked something or didn’t like something, or the manner in which he liked something. Occasionally, I might have put an arrangement down on a song of his and he might have butchered it in my opinion. And I might think ‘you’ve just destroyed the continuity of what I wanted to do,’ but in the final analysis, what I was trying to do wasn’t important. It’s what he’s hearing, because it’s his music; it’s his vision.

There were other times were he might have a starting point on a song and then midway through a line he might have said ‘here’s something, what do you hear off of that?’ I might bounce something off of what he gave and he might bounce something off of me. And at the end of the song, I might be hard pressed to say what was mine and what was his – it really was a case of the whole being greater than the sum of the parts. Those were the circumstances that were more intriguing to me, because it was matter of us trying to get into each other’s heads. He had that relationship with other people, Sheila E particularly and of course Wendy and Lisa. From a conceptual basis, Wendy and Lisa were the two musicians in any of his bands who were able to tap into him on some subliminal level – they really did have a musical relationship that was closer than with anyone that he worked with.

My relationship was a little bit more from a player’s standpoint. Because of the tremendous drummer and percussionist that Sheila is, [it meant] that relationship was very important. Some of the more interesting and more enjoyable music from my point of view was when Sheila, Prince, Wendy and Lisa and I would just go into the studio and just jam. I’ve got quite a few tapes of sessions like that. Purely ad lib, instrumental sessions, where we’d go in and just make a lot of music. None of it was going to get released; it was for our own enjoyment. Wendy and Lisa don’t really come from a jazz background [but] they shared in the ability to be very spontaneous. Our ability to go in and spontaneously play some music and at the end of an hour come out with some music that at least we could say has some kind of musical validity and continuity. It may not have the harmonic sophistication of a straight-up jazz band, but the ethic was very similar. When Prince wanted to be spontaneous, he could be very spontaneous!

TLM: Which are the most memorable tunes that you recorded with Prince and were released?

EL: Some of my favourite Prince songs are the songs that I had nothing to do with. There’s no one Prince album that I’m going to listen to from beginning to end without skipping tracks. One remarkable thing about Prince is that he’s probably one of the most eclectic artists in all of pop music. The songs that I find myself going back to more often are what Alan and I refer to as his “boutique songs.” The greatest example to me is the “Ballad of Dorothy Parker” [on the Sign ‘O’ The Times album] – that’s just one of my favourite Prince songs. Interestingly enough that’s the song where he gave me the opportunity to go in and do a complete horn arrangement on, which he didn’t use anything from. That song was just so perfect without anything else. I happen to love “Anotherloverholenyohead” from the Parade album. I love Wendy and Lisa’s song, “Mountains.” [also on Parade] There’s a song which I don’t know has ever been released. It was a song of Wendy and Lisa’s and it’s known by various titles [including] “Welcome To The Rat Race,” but was actually called “Life Is Like Looking For A Penny In A Large Room With No Light,” It was Sheila, Wendy, Lisa, Prince, myself and a couple of horns and that was one my favourite songs. I liked “Girls & Boys.” [Parade]. “Strange Relationship” [Sign ‘O’ The Times] I absolutely love.

Sign ‘O’ The Times

TLM: You’re one of Miles biggest fans. How did you get into his music?

EL: I got into jazz at a very young age. Through the sixties, [saxophonist] Cannonball Adderley was one of my favourites. [drummer] Art Blakey, [pianist Thelonious] Monk, [saxophonist John ] Coltrane. By the mid to late 60s I had began to immerse myself in the avant-garde – John Coltrane and all of his disciples. Pharaoh Sanders is one of my absolute favourite horn players – Archie Shepp is another. All those Impulse! albums of the 60s. I was deep into Sun Ra [and] Rahsaan Roland Kirk was one of my favourites. John Handy, Byard Lancaster, Robin Kenyatta, Gato Barbieri – this was the music I was immersed in. For whatever reason, I had never gotten into Miles. I had [the album] Kind of Blue – everyone had that! I had Live at Carnegie Hall – I loved the version of “So What”; it’s my favourite version of it. [saxophonist] Hank Mobley played his ass off on that. I had [the album] Miles Smiles but couldn’t get into it. I’d read about Miles and he’d rag on [criticise] Coltrane and these guys and so I’d dismiss him – ‘man, he doesn’t get this.’

TLM: Did you listen to anything else?

EL: Aside from that that, R’n’B and particularly James Brown. Because I had such an opportunity to spend time with him, that music truly meant more to me than anything else. I never fantasised about being a part of James’s band – I would have loved to have been his band’s director – but I considered it to be jazz. I understand that it wasn’t in the conventional sense. But if you ever ask me who the greatest jazz singer is, I’d say hands down, James Brown, from the purest sense of absolute spontaneity and the ethic of using his voice. His voice was that of a drummer. That’s what he was – he was a walking time machine. And it was like he was a master drummer that was constantly improvising over one of the greatest bands that ever existed in any kind of music.

TLM: You’re talking rhythm here!

EL: Funk and rock are duple meter rhythms, and by the 1960s, that had rhythmically become the coin of the realm, it was the pulse of the street; that’s what people danced to. What I was desperately looking for in jazz was somebody who was going to take the ferociousness and the syncopation of the kind of rhythms that James Brown was utilising in his music and be able to take hard-core sophisticated jazz based on that kind of a rhythmic pulse. That wasn’t dumbed down into Boogaloo kind of stuff, which was basically what you got when great jazz musicians tried to make a pop album or something that tried to appeal to a pop audience. Nine times out of ten it would dumb down everything to foolishness. Occasionally something would come along that would kind of work, like Lee Morgan’s Sidewinder. Charles Lloyd’s group were starting to break the line rhythmically.

But the other thing I was getting into was the density of the rhythm of James Brown. The two rhythm guitars. The way he would use the horn sections and integrate them into the rhythm section. His use of two, sometimes three drummers at one time, in live performances anyway. I’d absolutely loved Coltrane’s Kulu Se Mama. He was utilising two drummers, extra percussion and there was this rhythmic density that was starting to get away from the conventional 6/8 triplet feel. And while it wasn’t quite funk, it was starting to get to a new place rhythmically. I would listen to [Coltrane’s] A Love Supreme and James Brown one after the other and it was like two sides of the same coin. I was thinking ‘somebody’s going to really bridge that gap and is going to change things.’ You could see people moving towards that.

TLM: So how did you build your Miles Davis collection?

EL: All of this time, I was completely unaware of what Miles was doing. So finally, one day in the fall of 1969, I’m in the record store and just browsing. I come across the bin for Miles and I think ‘look at all these records. I’ve really got to see what this cat is all about.’ I look for his most recent album and it’s In A Silent Way and I look at the personnel and think ‘oh my God, Joe Zawinul is on it. He was one of my absolute heroes and had been from the time he joined Cannonball. I was already getting into Chick Corea through an album he had done with Bobby Hutcherson on Blue Note called Total Eclipse. I knew Herbie, Wayne Shorter and Tony from their work with Miles, but I’d never heard of [guitarist] John McLaughlin and Dave Holland. I notice there are three pianists on it and I wonder if they just play individually on three tracks. But then I think, ‘oh my God. If these guys are playing on the same song, that’s going to be very interesting! I took the album home not knowing what to expect and I put it on and I don’t think I listened to anything else for a week – that album just blew me away. The sonic textures, the polytonality, the density of the keyboards – everything about that record was ‘my God, I’ve never heard anything like this.’ There was a part of me saying this is as close to what I have been wanting to hear. It’s not straight-up hardcore funk rhythms, but it’s getting there. To this day, Miles’s solo on “Shhh/Peaceful” to me is of the greatest solos in all of Miles’s recorded work.

TLM: It obviously made a big impact.

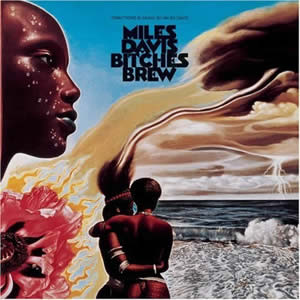

EL: All of a sudden I’m saying, ‘I really need to get into this.’ As the months went by, I started to see the advanced promos for [the new Miles album] Bitches Brew, because Columbia [Records] did a very big campaign for that. I remember the ads they ran in Down Beat and they had a picture of the cover and it said ‘A novel by Miles Davis in store soon.’ Then I started to read the initial press release and saw all of these guys that were going to be on it – Jack Dejohnette, Chick Corea, Larry Young, Joe Zawinul. He’s going to have two bass players, what, three drummers – this could be James Brown!

There have been two times in my life when I’ve been in a record store waiting for them to unbox an album. That was for Bitches Brew and when the first Weather Report album came out. I had a friend that worked at National Record Mart, a big Pittsburgh record chain. I got home from school and drove down town and he had a big box on the floor in the jazz section. He opened it up and pulled out a copy of Bitches Brew. I just grabbed it and drove home. I was an inveterate needle dropper, but of course with Bitches Brew it was just one track per side! All I remember is that I put on “Pharaohs Dance” because that was written by Joe Zawinul. Then I listened to a bit of “Bitches Brew” but I gotta tell you, when I got to “Spanish Key” it was all over. I don’t think I got to the other sides for another day – all I did was listen to “Spanish Key” over and over again; and I called Alan [and said] “Dude, you gotta go out and get this album because the world has just turned. Everything I wanted to hear was there. It was not dance music – I was not looking for dance music – I was looking for a rhythmic sensibility that similar in syncopation to what I would feel rhythmically from James Brown but still was hardcore jazz with nothing dumbed down about any of the process and the methodology.

I had Kind of Blue and I wondered how do you get from there to this? That’s when I started filling in all the gaps. Within probably a year after that, I had all of his Columbia records. What intrigued me was how Miles got to where he did. I heard the albums like ESP, Miles In The Sky, Nefertiti and Filles de Kilimanjaro and all it made perfect sense in retrospective. And the more I read about where Miles’s head was musically during those years and the fact that he was listening to James Brown and R’n’B, and so he was looking for the same thing. It occurred to me years later, that the most important thing in Miles’s career was that he be relevant to whatever was going on at any given time. And his embrace of duple meter rhythms makes perfect sense in that regard. He realised that nobody listened to swing rhythms anymore – it was no longer the pulse of the street anymore. For me, what Bitches Brew was in 1970 was every bit as impactful and as important as Kind of Blue was in 1959. It was a statement that music is going to be different now and so much of what happened after Bitches Brew bears that out.

***

In part two of this interview, Eric talks about many more things including, the relationship between Miles and Prince, the stories behind the Prince/Miles track “Can I Play With U?” and the Chaka Khan track “Sticky Wicked,” the Madhouse project, meeting (and having dinner with) Miles, playing live on-stage with Miles and Prince, the music Eric created for possible inclusion on Miles’s final album and his thoughts on Miles’s music of the 1980s.

You can read Part Two of this interview at TheLastMiles.com

Many thanks to Eric for all of his time and also a big thanks to Alan Leeds for his help and support.

Thanks also to great Prince fan sites Dawnation and Housequake.com for linking to this piece.