Recording engineer Eric Calvi was involved in the recording sessions for the Decoy album, little knowing that three years later, he would be the engineer on the second batch of recordings that made up the Tutu album (“Tomaas,” “Perfect Way,” “Don’t Lose Your Mind,” and “Full Nelson.”). He also worked on some of the sessions for follow-up album, Amandla. In this exclusive interview for The Last Miles.com, Eric recalls those sessions and considers Miles’s musical direction in the 1980s.

Eric Calvi – copyright © Eric Calvi

TLM: Can you tell us a little about your background?

EC: I was born in the heart of Paris in 1959. I grew up in the suburb of Paris. My father was born in Italy and moved to France. I fell in love with music at an early age. In my teens I formed all sorts of bands. I played the guitar and was inspired by people like Frank Zappa, Robert Fripp, George Benson and John McLaughlin. Being French I was very much into jazz-rock and classical music. I bought my first pop record when I was twelve, the British band Osibisa. Eventually I got into all the rock stuff, bands like Pink Floyd.

TLM: Then what?

EC: I decided I wanted to be a jazz guitarist and study music. In 1980, I left France, went to New York with one of my friend, and told my parents that I wanted to be a sound engineer, so that they would agree to finance the trip! Six months after arriving I got a job at a studio called Sound Ideas – which is now closed. It was one of two studios in the East Coast who had the very first multi-track digital machine – the 3M. The other one was the Soundworks, Steely Dan’s studio. It’s interesting that classical and jazz have always been driving music technology. The first studios to adopt digital multi-track technology were studios that recorded a lot of Classical and Jazz recordings. Later rock and pop band got interested in it. Anyway, In NYC I started seeing many jazz bands. I also got exposed to rock and later on got into hip-hop – I was living near Harlem so I heard a lot of the music. I also got into dance music – I was a member of a club called The Loft, which was playing all kinds of progressive dance music. So at some point I was an engineer during the day and playing in a rock band at night. Being a tech guy in the studio meant I got promoted quickly and started working at the Hit Factory around 1982.

In 1984, I joined The Record Plant in New York as an assistant engineer. It’s interesting because at the time I arrived, Cyndi Lauper was recording her first album [She’s So Unusual] which contains the track “Time After Time”, later on covered by Miles. One day we get the call that Miles is coming to record! I was very exited at the prospect of maybe meeting him… Meanwhile, turns out that none of the other assistants who were basically rock guys were particularly interested in working on a “Jazz” date (even if with Miles.) So it was like “Eric, will you do it?” and I’m jumping up and down and saying “Can I please do it?!” Because back in France I was so heavily into Miles. I liked Kind of Blue but my big influences were Big Fun and Agharta.

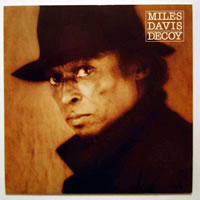

Decoy

TLM: Miles was recording Decoy?

EC: That’s right. So Miles comes in and I’m the runner. Of all my experiences with Miles that had to be the most enjoyable because I had virtually no responsibility other than functioning as a kind of personal studio assistant to Miles! Later when I was engineering Miles’ albums, there was understandably more pressure and less time for socializing. To describe Miles at the time, I would call him the Prince of Darkness, which was fine in my book. He had long braded hair and dressed with long black coats… and his piercing eyes gave him the aura of a shaman.

TLM: How did Miles work in the studio?

EC: On Decoy, I found his recording technique to be unconventional compared to that of your typical rock or pop band. The band was set up all together in one medium sized room and they would record for hours without much talking going on… from the outside, you got a sense that they were just jamming. So you set up two multi-track machines and when you get to the end of the reel on the first machine, you start the second machine so you can record the music without losing anything or the musicians having to stop… Miles and the band might go on uninterrupted for three hours and you would record everything. On Decoy, I don’t recall Miles coming into the control room once. He would come into the studio, put his bag down and do what he had to do. Work, play, maybe go into the lounge but never go into the [control] room, even to listen to the playback. He would get cassettes at the end of the session, listen to them at home and select which parts of the day’s performance were keepers.

I remember that Miles was set-up in the middle of the room with his Oberheim [synthesiser]. He liked a function on it that allowed you to capture a chord, so he would play a chord and press a button and the chord stayed sustained indefinitely. That was interesting because he was creating a musical space where the harmony wouldn’t change, which was very modern at the time. If you look at hip-hop today or dance music in the 1990s, they totally removed the harmony progression – it’s like one-chord. He was like totally ahead of his time. So the way it worked with him was that if you were a fly on the wall you had no idea what the fuck was going on. It was like Miles moving around in the studio talking to musicians while they were playing, subtly tweaking their performance but you never had a sense of an overall game plan. All this was possible because of Al Foster who functioned as a sort of rhythmical anchor keeping the continuity throughout. You also had John Scofield – also known as the librarian possibly because he did seem a little serious at times! – and Darryl Jones. I have no recollection of Branford [Marsalis]. [Percussionist]. Mino [Cinelu] was a fiery character. Al Foster was like the assistant shaman.

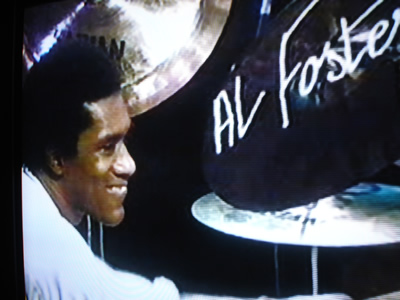

Al Foster

TLM: So it was all very loose in the studio?

EC: They would be working on a track and they would stop and go back. Al Foster had a little drum machine that was used as a sophisticated click [track]. Al played with the economy and precision of a drum machine which was a very modern approach when you think how busy jazz drummer can get. Miles allowed the younger kids to fuck around. He would say ‘I play this F-sharp and you figure it out!’ He never wrote the song out nor rehearsed the song. The musicians would fill in the blanks. He would go in and let the band play. It always sounded great… inspired… and I would think ‘That’s the take!’, but he would keep them playing and go on and on. It’s not like they wrote a song and played it – never! And at some point, when you had stopped listening and they were still playing, you’d go ‘Wow! It’s there!’ And it was there. They all got there together. He never told them what to.

He was a true leader in that he created a space for his musicians to get to that level of music. Miles’ soul was on this record. The making of Decoy was a spiritual, meditation practice. It was a master class, which was recorded and released. All these musicians were already masters of their respective instruments, Miles’ contribution was to teach them about higher understanding of music making. Decoy is more of an ensemble cast that a soloist showcase. I thought it was amazing. [keyboardist, co-producer] Robert [Irving III] was central to this process. Robert functioned more like an arranger – he was concerned with structuring the raw material that Miles and the band was creating. Miles was bringing the gold and Robert was like the jeweller.

TLM: I gather you left the sessions earlier than planned!

EC: At the time, I was definitely thinking I was going to be a musician and not an engineer. I got fired from the studio toward the end of the Decoy sessions because I got a record deal on Elektra (with my band) and I had to excuse myself from a Miles session in order to go to my own recording session. Miles sessions were technically complex to set-up because of the dual multi-track machines. They would also record at a tape speed of 15ips [inches per second] instead of 30ips in order to get more recording time on each reel ( it also gives a warmer and broader bass response… reggae is mostly recorded at 15ips) Slower tape speed means more hiss so they used Dolby [noise reduction] which was difficult and time consuming to set-up.. Setting-up the session took two hours. Miles was always ahead, stretching technology.

TLM: What did you do next?

EC: I started working for the first hip-hop label, Tommy Boy. They had released “Planet Rock” [by Afrika Bambaataa and the Soul Sonic Force]. Not only it was the first hip-hop single but it also sold 800,000 units. I was their house engineer/producer until 1986. For me that was a great opportunity creatively because hip-hop was such a vital new form of music.

Tutu

How did you get to work on Tutu?

EC: I got a call from a friend of mine [keyboardist/producer] Philippe Saisse. He was producing a track for Chaka Khan with Arif Mardin. What happened was that Miles had gone to Warner. Tommy LiPuma – whom I didn’t know at the time – calls Arif Mardin and asks him to recommend an engineer because his usual engineer Al Schmitt had an accident fixing his roof and had (temporary) lost part of his hearing in one ear. So Tommy calls me and offers me to work with Miles!

TLM; Can you describe how Tutu was recorded?

EC: We worked in New York at Clinton Studio. At the time, it had one of the largest recording rooms in New York – you could put a large orchestra in there. But in the end we ended up using the smaller room, Studio B. With Tutu, I saw a different Miles. He wasn’t as central to the recording process as he was with Decoy – Marcus Miller was in charge of putting the album together. Often it felt like a Marcus Miller record with Miles overdubbing. Miles was not so hands-on on that project. Not to say that he didn’t make the final call on what got on the record or who got to play. But unlike Decoy, where he was performing in the studio, both as a musician and a leader, Miles took more of a back seat. Marcus and Tommy were providing him with ideas and he would choose what he liked. I was happy to see Miles again although he wasn’t there much. Most of the time it was just Marcus, Jason Miles, myself and sometimes a musician.

TLM: Was it the first time you worked with Marcus?

EC: No. The first time I worked with Marcus was at Record Plant on a Roberta Flack session. She would have 30-hour sessions I was the young guy responsible for the vocal punch-in – it was an intense experience! She was ready for digital recording where you can punch-in [drop-in a section] vocals in the middle of a syllable and it still works, but we had 1970s technology so it didn’t always go well! Marcus came in as the arranger. He was very young, maybe 22 and it was a big job working with such a legendary and therefore demanding artist. From the beginning, Marcus commended respect. It was clear to see his tremendous potential and the power he had in terms of processing, intelligence, knowledge, inventiveness, originality and of course craftsmanship.

Marcus Miller

TLM: What hours did you work on Tutu?

EC: We’d start around 11am and go on until about midnight or 1am. Miles would come in the afternoon, which was good because it gave everyone time to write and set things up. [Programmer] Jason [Miles] was Marcus’s right-hand man. Jason would provide sound palettes for Marcus, which would inspire him with the production. I think Marcus grew a lot on that project. He would play the bass, the bass clarinet, percussion, keyboards – all of it.

I had previously worked with Marcus on one of Grover Washington’s album, where Marcus played everything [Strawberry Moon and the track “Summer Nights”]. He was always using his Linn II drum machine, which was low-tech at the time compared to what was available but it had a “sound” which really worked well for Marcus. Jason Miles had the high-tech stuff. Many of the keyboards lines were programmed using step program, sequencers and all that, which was totally in line with what was going on at the time. We loved that, we were into it. Marcus would start by putting a bass line over Linn drums. You could guess that he had all or most of the arrangement in his head already – he’s got tremendous brain power. Marcus is a tremendous technician – the guy is hard to top. He’s like the Trevor Horn of jazz. He had a total vision before we got started. He was from the younger generation and totally into using the studio as an instrument.

TLM: So everything was prepared before Miles came in?

EC: It was basically done like a pop record. Marcus recorded the tracks first then Miles came in and over-dubbed the trumpet – pretty much like when you work with a vocalist.

TLM: What was Miles like on the sessions?

EC: I thought Miles was restless and not that happy. He was somewhat aloof. During Decoy, Miles was sweet. I would help him with programming his keyboard and he would ask questions and show an interest for what was going on around the studio. During Tutu he appeared somewhat closed. In my opinion, he didn’t really want to be there. It was a real contrast with Decoy where you felt that he was there – he was into what he was doing. On Tutu, I didn’t think he was into it. That’s the impression I got. He wasn’t staying around extra-long or grooving that much in the studio. Seeing him work on Decoy was like seeing him live on-stage. Not on Tutu (and Amandla.) The head was disconnected from the heart. But it was the 1980s people were into working like that. I don’t think Miles talked to any of the musicians – he would talk to Marcus and Tommy. Marcus was comfortable with Miles but respectful and he was never taking it too easy.

TLM: What role did Tommy LiPuma have?

EC: Tommy was like the Guru on this project. He created the space for all of us to work together. That’s his strength – you feel creative when Tommy’s around. Everyone’s feel good when he’s there. He is a shining spirit.

Eric Calvi and Tommy LiPuma

TLM: How did Jason Miles and Marcus work together?

EC: You can really hear Jason’s contributions on the sound of the record. Tutu’s production is extremely contemporary, in the style of the time and using the tools of the time. Jason is a master at creating fresh sound palettes and that was good because we all wanted to do a cutting edge album. Using these sounds, Marcus was working a lot on the voicing, the inner voicing of the chords, creating colours – watching him work often reminded me of Gil Evans.

TLM: Tutu was a big surprise for many of Miles’s fans

EC: At the time, I could see why Miles went with Warner. First he got a big chunk of money and deservedly so. And remember Miles was less successful in the U.S. than say, in France or Japan. It’s also the period when Miles switched to doing pop music. In the 1970s, if you wanted to hear the most progressive music, you’d be listening to King Crimson, Kraftwerk, Pink Floyd, Herbie Hancock to name a few and of course Miles. In the 1980s that was all gone – pop music totally edged out the experimental stuff. Producers became the new stars. Miles knew that and that’s why he made “You’re Under Arrest.” Eventually it made sense to make a record like Tutu, which is a true jazz crossover album unlike anything he had done before.

TLM: What was Miles like to record? Some engineers say it was challenging while others describe him as a joy to record.

EC: Typical Miles! Lets say Miles wanted to play sitting down that day because he didn’t feel that good. We would spend twenty minutes making sure he was comfortable with the microphone position and the headphones mix. So you would get everything ready and now the tape is rolling and the first thing he does, is to stand up and starts playing in the air away from the mike! So you’d stop the tape and put a second microphone up in the air, so now he can stand up or sit down. I think he liked moving around and not just sitting down and overdubbing. Most of the time in spent in the recording booth he was by himself.

TLM: How did Marcus work with the session musicians?

EC: Marcus would get some of the musicians to come in the morning, do some overdubs, and run them by Miles in the afternoon.

TLM: There was a video crew at these sessions and some footage of Miles playing ” Perfect Way” has appeared in public.

EC: In fact, there was a TV special on the Making of Tutu and there’s an embarrassing moment where Tommy says to me “You didn’t erase that did you?!” (referring to one of Mile’s takes) and I’m going “No, I didn’t!”

TLM: Did you work on the Prince track “Can I Play With U?”

EC: Yes, we mixed it, but it never got released.

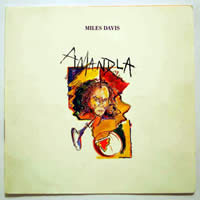

TLM: You also worked on Amandla. What was that like?

EC: I didn’t work on Amandla a lot, I probably did like six or seven sessions. Amandla and Tutu went on like pop records, whereas with most jazz records you went on for a week or so. You could tell they wanted to make the album a little more live compared to Tutu. I remember the exciting sessions with Ricky Wellman – he is such a refined and inventive musician. And there was Foley playing a four-string guitar. He is a guy who is fully self-expressed and truly an original. We laughed a lot with him. I also remember when Kenny Garrett started playing for the first time on the album. He would combine a series of styles all in one solo! Recording Kenny was like the highlight of the project for me. The first time we got Kenny Garrett and it was like “wow!” I don’t think we had wow moments while recording Tutu. The wow moment on Tutu was more at the mix; when every element was in its place.

TLM: Why were you only involved in the early sessions?

EC: At the time I started detaching myself from that world – the Tommy world, the Marcus world, because I always long be into “what’s next” and after many years working for that team it felt like we were losing our cutting edge. There was little or no innovation. I started working with lots of British bands due to having mixed “Word Up” for Cameo. I worked with Prefab Sprout, Thomas Dolby , Aztec Camera, Neneh Cherry and similar artists. So during Amandla I wasn’t really there… Miles wasn’t around much either… I wasn’t into it. I don’t think I was fired as such, more that they put me out of my misery. I probably wasn’t fun to be around either.

Amandla

TLM: What made you unhappy about Amandla?

EC: I felt that it was really Marcus’s show and Miles showed up to do his bit. If Amandla had been like Doo-Bop, you couldn’t have gotten me out of the room! When it comes to Miles’s electric music, for me, it’s Agharta, You’re Under Arrest and Doo-Bop. Tutu was kind of a negative experience for me with regard to the music. You have to make a distinction between Miles and his music, and music comes first. I think Miles would silently agree with this but never say it. I was already wishing for an album like Doo-Bop. I would have loved to work on Doo-Bop – that is Miles’s music.

TLM; What’s your take on Miles as a person?

EC: Miles put us through challenging times just by being who he was. He made us re-examine ourselves. He was not protective of himself – he made himself constantly vulnerable and that was his strength. He was for us what we reflected on him – a soul mirror. I found him to be the most deeply human person I’ve ever interacted with. Not good or bad – it’s well beyond that. Miles embodied the full range of human traits. You could experience him as a prince or as an obnoxious person but always courageous and supremely authentic.