During the last ten years of his life, Miles collaborated with many artists including, George Duke, Toto, Paolo Rustichelli, Shirley Horn and Scritti Politti. But the collaboration that captured the most imagination was that with Prince. Miles performed a number of Prince’s songs on-stage, recorded a Prince tune that was due to appear on Miles’s first album for Warner Bros, was going to record a bunch of Prince songs for the album that became Doo-Bop and Miles even appears with Prince on a track with Chaka Khan (“Sticky Wicked” on the album CK). But like the long-hoped for collaboration between Miles and Jimi Hendrix in the 1960s, Miles and Prince never got to work together in a studio on an album. It’s not even certain whether they ever performed together in a studio.

Miles had great respect for Prince and vice-versa and Miles once said that Prince could even be the Duke Ellington of his time. Such is the importance of this musical link that my book, The Last Miles, devotes a whole chapter to Miles and Prince.

The man who introduced Prince to Miles was Alan Leeds. Alan has had a remarkable career in the music industry. He was James Brown’s road manager for over four years in the 1970s and was co-writer of the liner notes for the highly acclaimed James Brown anthology Star Time – Alan shared a Grammy award for the notes.

Alan also worked with Prince from 1983 to 1992 as tour manager and later, head of Paisley Park Studios. And there’s another Prince connection, as Alan’s brother – Eric Leeds – played saxophone in Prince’s band and played on the Prince/Miles collaborations. Alan is also a serious Miles fan and has an encyclopaedic knowledge of his music. In this excusive interview with The Last Miles.com, Alan describes the relationship between Miles and Prince and talks about the number of occasions when they got close to actually working together on an album.

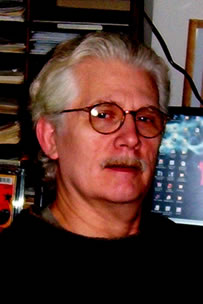

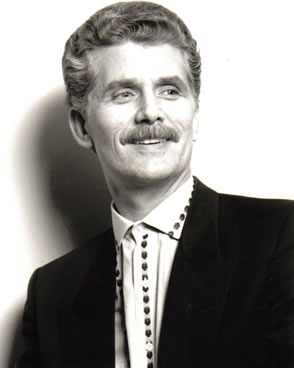

Alan Leeds. Photo courtesy and © Alan Leeds

TheLastMiles.com: Alan, can we start by looking at your background?

Alan Leeds: I was in born in Jackson Heights, January 26 1947. For some reason I became a fan of black music. Most of my family’s taste was in classical music but my father also had his share of Count Basie, Duke Ellington, Benny Goodman and stuff like that. It was through that that I was introduced to the ensemble of black music. Then I would see people like Louis Armstrong on TV. God knows why, but I took to the music. Very early on I had very segregated musical tastes and if it wasn’t black, it didn’t count! And even when I got a little older and into rock and roll, it was like “well Elvis is okay, but this guy Little Richard is a little more fascinating!”

My uncle happened to be the programme director of WINS radio in New York, which was at that time – mid to late fifties – the leading rock and roll station. As the programme director he had tons of spare records and he would gather records from the radio library that they didn’t need – either because they were duplicates or records they had no intention of playing. So he’d gather up all these 45s and send them to us. So I’m this ten, twelve year-old getting a box of hundred records every month and of course it made very popular with the kids on the block! But it also exposed me to all kinds of records that weren’t necessarily on the radio. A lot of them were records that were only on black radio or were not on the radio at all. So I would get records by Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf that were on exotic labels and you just wanted to put them on.

TLM: What about your education?

AL: I was an okay student and was blessed with a kind of brain where I could get by without applying myself too hard. So I managed to get through college and do two half years as a journalism major. Most of my growing up was spent either playing baseball or listening to music – I was obsessed with records. As I got to older, my family moved to Richmond, Virginia and ended up working part-time in a black radio station [WANT] in Virginia, which was another oddity! I was attracted to fact that this station played the music I liked. Through a quirk of fate I met one of the disc jockeys, who was a black guy who was in college – this was around ’62, ’63. We took to each other. I was managing a small local band and used this to talk to the DJ about utilising the studio to rehearse the band, but it was really all an angle to get into the station and try to get access to the record library! I reasoned that if my uncle’s station had extra records, maybe this one did too! Lo and behold, they had a record library that was in complete disarray and so I volunteered to become their part-time librarian and they bought it. That led to being a disc jockey on the station, first part-time and then full-time.

Alan Leeds then… Photo courtesy and © Alan Leeds

I wasn’t really committed to radio. I loved the fact that people were paying me for sitting down and playing records – after all, that’s what I doing at home for free – but I didn’t have any aspirations of being a life-long broadcaster – the fascination was with the music and not the medium. But the radio station I worked for promoted a lot of the rhythm and blues acts that came through Virginia and in those days, Richmond was a major stop on the Chitlin circuit, so all of the legendary R & B stars of the 1960s – Jackie Wilson, Otis Redding, James Brown, Sam Cooke – came through town on a regular basis. I used the radio station as leverage to meet artists, agents and management, and it was clear to me that I wanted to be part of that – this was where I wanted to spend my life. As exciting as records were, it didn’t match the excitement of a concert, where the curtain would go up and thousands of people would scream and this incredible music would come to life.

Being in the right place at the right time, I went on to form some relationships, one of which was with James. The idea was that I would volunteer to interview these guys – either backstage, or at their hotel or wherever they were available to be interviewed. I would play the interviews over the air, help plug their records and promote the ticket sales for the shows, so it was a win-win for everybody. The rest of the guys weren’t as aggressive as I was – they didn’t have the passion I had about the music. They were trying to get home to their wives or girlfriends and I was trying to get to the hotel and interview James Brown!

James Brown – Star Time

TLM: What was your take on James Brown?

AL: For some reason James Brown took to me and vice-versa. I was already a number one James Brown fan. If there had been a competition to find the number one James brown fan I defy anybody to take me on – I would have won hands down.

TLM: What was your first meeting with James Brown like?

AL: It was crazy! I came to a hotel room and I had heard about his temperament, that he was a highly strung, unpredictable guy, who was very impulsive and reactionary. He could be the sweetest guy one day and jump down your throat the next. I was really very timid. Of all of the guys I met back then, he was the one that intimidated me the most, because I was just a fanatic. It was ’65, so I’d be eighteen. A very attractive woman answered the door and seemed taken aback that it was a pimply-faced white kid – I don’t think she expected that! I explained who I was and I had this heavy tape recorder with me. It was the middle of the summer and I was probably soaked with sweat. She invited me in and I sat in the living room for about five or ten minutes and then she came in and said ‘Mr Brown will see you now.’ I expected him to walk out but she escorted me into the bedroom. It was the afternoon and he had a show that night and he was lying in bed.

All I saw – and it’s a vision I have that’s just as clear today – was white sheets and a whole mass of white pillows propped up against the headboard and on the pillows was all this hair – I didn’t even see his face, it was just hair! I introduced myself and we sat and chatted and he made me feel like the biggest thing in radio since Dick Clark or something. He just had this way if disarming you. Of course, this was a guy who was a master promoter and a guy who befriended people and anyone who could help him. He was just beginning to crossover into the mainstream – he had released “Papa’s Got a Brand New Bag” – and I think that the phenomenon of white media giving him attention was something I think he was enjoying, even though ironically I was representing the black media.

James Brown – Gravity

He took to me and spent way more time than he had to and he did some drops [promos] for my radio show and some little promos way beyond the call of duty and we chatted about the industry at large – we chatted more off-mike than on. He wasn’t treating my like a Johnny-Come-Lately – he was treating me like an industry veteran. I was just on cloud nine – “this guy is treating me like a big shot and I’m just a nobody!” Of course, years later I realised that was how he treated anybody on radio and that his attitude was today’s new disc jockey could be the programme director a year from now. He treated disc jockeys like that in every city, who also felt they were special. Unless that is, you didn’t play his records, in which case, you met the other side of James Brown! I got to the point where whenever the James Brown Show was appearing within a hundred miles of me, I was in my car and chasing the band. So I would see him almost once or twice a month. As a result I became a familiar figure backstage and because the boss liked me, everybody tolerated me! I’m sure a lot of guys in the band and the entourage were trying to figure out this scrawny little white kid was! Some of them became friends.

In 1969, he was having a problem in Pittsburgh, which I had moved to and was going to college. I got a call from one of his agents, who said ‘we’re having a problem with the local radio station promoting the show, and we need a local promoter. James suggested calling you to see if you had time to help us with the show, can you help?’ Of course, this was the call I had been waiting all my life. I did it and the show sold out and I got offered the job. So I quit school and went to work for James Brown. And after four or five hectic years of that, I’m in the business now.

TLM: How did you meet up with Prince?

AL: We’re now talking early 80s and I had become a freelance tour manager and I was on the road with Kiss of all people. The tour was winding down and one of the production people came up to me and said ‘what are you going to do after this?’ and I said ‘I don’t know.’ He said, there’s a vacancy on the Prince tour that was halfway through’. The word was out that Prince was difficult to work for and I guess he’d been through two or three tour managers on this particular tour. This guy had a contact with Prince’s management who asked if I was interested in leaping over to the Prince tour. I just looked at it as another job opportunity, so I said “Yes.” We kind of hit it off and at the end of the tour I went home – by now I’d moved back to New York. About three months after the tour ended I got a call from his management asking me if I would be willing to relocate to Minneapolis because they going to do a movie and a new album and had all these activities scheduled that sounded overly ambitious and unrealistic to me. But they were determined to make it worth my while, so I did. And of course Purple Rain came out and I realised they how right they were. It was another case of being in the right place at the right time. I worked for Prince from ’83 to ’92 and arguably, if you were going to work for Prince, they were the years to be there. Purple Rain blew up and he eventually built Paisley Park Studios and became the industry he was for about ten years there.

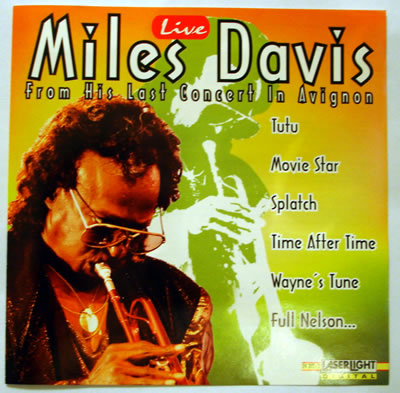

TLM: Tutu engineer Peter Doell talked about how incredible it was that Prince could compose, play, record and mix a new song in a day.

AL: The description is absolutely right – it was a phenomenal experience watching him do that. He has a very anal kind of compulsion to finish things. I suppose you could look at some of his records and say they could have benefited from a little more time, sonically as well as creatively, in some cases. But his genius was in that he would get an idea and just couldn’t rest to the degree of burning out engineers. He was an engineer’s nightmare because he had no patience with the technology – just waiting for them to rewind tape was tedious for him, even to the point where he would yell at them and say ‘can’t you make that move a little faster?’

Prince And The Revolution – Purple Rain

I don’t know if he’s the same now or whether he’s calmed down with age. But he was incredibly prolific and compulsive about finishing things. It wasn’t unusual for him to get an idea for a song and go downstairs at mid-day and start, and by nine or ten at night, come up with a rough mix of a finished song. And when you consider that he does it all himself and that a finished song represent countless overdubs of various instruments, not to mention the adjustment because the composing is part of the process. Half the time he’d have the lyric and the song would just evolve as he was working – it was pretty amazing. But he couldn’t rest. He’s not the kind of guy who say ‘okay I’m going to lay down a drum track and bass track and go live with it for two days – the live with it part just wasn’t in his vocabulary.

TLM: Where did you get your love for the music of Miles?

AL: Back in my Richmond days I was completely obsessed with R&B and wasn’t listening to much jazz. My Dad exposed me to the bands that he liked and as a kid I would go see Duke Ellington or Count Basie and enjoyed them tremendously and even had one or two records in my collection. But in terms of any modern jazz, I didn’t go out of my way to expose myself to it. But I met a friend who worked in a record shop who was a real jazz-head and he was the kind of guy to turn me onto new things. He exposed me methodically to modern jazz, which falls into the hard bop category. He turned me on to Cannonball Adderley first and then onto Miles and Monk and Mingus and so on. The first Miles record I ever bought was the album with Hank Mobley on sax [Miles Davis at Carnegie Hall]. Gradually I went back and got Kind of Blue. I wasn’t into the second quintet – I wasn’t open minded enough at the time to appreciate them. But if you ask me now what’s my favourite Miles stuff it’s the Coltrane quintet, the Wayne Shorter/Herbie Hancock quintet and then I make a leap and go to Agharta. While I love the Isle of Wight and the Keith Jarrett and the Bitches Brew stuff, if I’m going to play any post 1960s band I’m going to play Agharta. That funk band was amazing. I think that band [with Pete Cosey and Reggie Lucas on guitar, Michael Henderson on bass, Al Foster on drums, Mtume on percussion, Sonny Fortune on sax and Miles playing wah-wah trumpet and organ] was Miles’s greatest casting.

TLM: How did Prince view Miles?

AL: Eric joined the band in the middle of the Purple Rain tour and quickly became friends with [guitarist] Wendy Melvoin and [keyboardist] Lisa Coleman, who were familiar with jazz. Gradually they began turning Prince into this kind of music- he had little first hand knowledge of jazz. This was during 1984/85. They made it their own project of turning Prince onto different kinds of music. Eric would give him jazz records and turned Prince on to Sketches of Spain and Kind of Blue and other stuff. Gradually the three of them had an impact on Prince and he felt that he needed to know this music and figure out what he liked and didn’t like. He had a very genuine interest in expanding his musical curiosity. Young black guys were attracted to Miles because of his politics – he was an icon. I think as Prince learnt more about Miles he started to see some of himself in Miles. He was fascinated with Miles and used to ask Eric about stories about Miles and he’d share recordings with him. He’d show him video recordings and Prince would be fascinated and say ‘look at the way Miles is standing.’ – he was just studying his moves or his posture. There was a real fascination with the iconic aspect of Miles.

TLM: Can you describe the first time they met?

AL: To my knowledge, it was at Los Angeles airport and according to my diaries it was December 7 1985. I was with Prince and we had been in San Francisco and were flying back to LA. We got off the plane and were walking to baggage airside and towards where Prince’s driver was waiting. And as we were walking through baggage claim I spotted Miles Davis and I poked Prince in the ribs and pointed. I introduced myself and it ended up with Prince getting into Miles’s car, which was parked a little in front of his. I didn’t get in with him and they sat and chatted for twenty minutes or so and swapped phone numbers. Prior to this, Miles had signed with Warner Bros and I’m sure there had been some conversation with Warner executives about the possibility of him doing something with Miles. We knew Miles had aspirations beyond the jazz category, and so it was a no-brainer to think ‘We’ve got Miles and Prince under one roof, let’s get them together.’ It just made perfect sense. Prince had recently discovered Miles’s music and his history and had a kind of falling in love with him as an icon to the same level as James Brown. He even began with Eric’s help to rearrange some of the music, putting in jazz-based segues. There was actually a break between two of Prince’s song where they would do “Now Is The Time”.

Madhouse. The first jazz-influenced album

Prince and Eric Leeds recorded together

That led to Prince and Eric doing this Madhouse album [a jazz-influenced project]. So all of sudden Prince decided this was the music he should spend a little time on and thus began a second Madhouse album. So all of this was in the orbit when Miles intersects with the camp. The jazz radar was at its peak in the Prince camp when Miles intersected with the camp

[In late 1985, Prince composed and played on a tune for Miles called “Can I Play With U?” which Miles recorded]

TLM: Can you explain how “Can I Play With U?” happened?

AL: I’m basing this on my files and Eric’s journals and his recollections. Shortly after the meeting at the airport, they swapped numbers and I’m sure they talked about Prince submitting some material for the first Warner Bros album. As I said, there might even have been conversations before they met Tommy LiPuma [then head of Warner Bros jazz] and the Warner Bros people. So it was already in our mind that ‘Miles was on Warner and you guys are going to end up doing something together.’ Now, they’ve met and swapped numbers, it was more imminent. And once Prince has got a passion for something, he jumps right on it.

Within a couple of weeks, Prince was in the studio and he recorded the initial track was on the 26th and 27th of December 1985. Eric was in Florida on holiday with our parents and he got a call from Prince saying ‘hey you gotta come round here.’ Prince did the basic track on the 26th and Eric overdubbed his horn on the 27th. Eric recalls Prince intending to take the tape to Miles in Malibu and Prince said to Eric; “I’m going to take this tape to Miles in Malibu. Do you want to go?’ And Eric was well up for it! I don’t know why, but that meeting never happened but they sent the tape by messenger. In January [1986] Prince sent the multi-track tape to Miles for him to do whatever overdubs he wanted to do. This didn’t happen until February and March. Prince was never present at any of those overdub sessions – he had absolutely nothing to do with them. He was enamoured with Miles but I don’t know how ambitious Prince was about working with Miles.

TLM: It seems that Miles always wanted greater collaboration but Prince never seemed to countenance them working together in a studio on an album. Why was this?

AL: First of all, you’re dealing with two people who are control freaks. And if Miles is a control freak, multiply that five when you come to Prince! As enamoured as he was with Miles, it was never to the extent that he wanted to sacrifice his control. By the same token, there was Prince’s MO [modus operandi] of producing other people – by then he had produced Chaka Khan, George Clinton, Patti Labelle – throughout his career. His idea is not the standard producer/artist relationship He just simply writes and produces a track that he thinks would be good for an artist and then he’s willing if necessary to supervise the vocal overdub in the case of singers, but he doesn’t really like to do that. He’s uncomfortable directing other artists that he respects. He doesn’t see himself in the role of a traditional producer, whose job is to bring out the essence of what the artist is. With Prince it’s a matter of ‘This is how I do it and here’s how you could fit in. Give it a shot and see if you fit in.’ But he’s not going to change what he does to fit the artist, so in that sense he’s really not a producer, at least of other people. And I think he realises that about himself, that lack of flexibility of as a producer.

And Eric reminded me of a quote -and here I’m paraphrasing – he remembers Prince saying to him ‘I can’t imagine what it would be like to tell Miles what to do.’ In other words, ‘I wouldn’t want anybody telling me what to do, so how dare I tell the great Miles Davis what to do.’ So the idea of being in a studio with Miles and trying to direct him was foreign to him and he just couldn’t even conceive of that scenario. The irony was that Miles would have welcomed it and that’s what we were trying to get through to Prince. Unlike Prince, Miles was somebody who was open to that and who would be interested in seeing where you would take him. Miles had the spirit of adventure to be wide open to see what it would be like for you to direct him as a producer. It was really all about Prince being completely intimidated at being in that role and how he really couldn’t understand someone being in that role.

TLM: Prince pulled the track from the album.

AL: I remember Prince’s reaction when he got the tape back – he wasn’t enthralled with it. Not so much because of what Miles had done with it. But he just lived with the song long enough and realised that there wasn’t really anything brilliant about it. It was something that had been hastily and impulsively done. I feel certain that Prince felt that if there was going to be a collaboration that was officially released, it should be something more significant than what that track was. That wasn’t a reflection of Miles’s playing, but more about the composition and the significance of the quality of the track in itself. He seemed to lose interest in that track and the fact that album ended up going in a different direction [Marcus Miller took charge of the album that became Tutu]. I think if Tommy LiPuma or Miles had gone back to Prince and said ‘look this track isn’t great. Let’s do more and let’s make an album together,’ I think Prince would have probably submitted twenty tracks. I don’t think it would have changed his MO or his willingness to spend a lot of time in the studio together, but I think he would have been interested in submitting tons of tracks in the hope of making an album. But that didn’t happen. Whether he was hurt by that, I don’t know, but I know he just seemed to lose interest.

[“Can I Play With U?” has been posthumously released and is available on both physical discs and streaming formats such as YouTube.]

TLM: What happened after that?

AL: They stayed in touch with occasional phone calls back and forth. There were a lot of invitations back and forth, where we would have shows on the West Coast and Prince would say ‘call Miles,’ but Miles would either be on the road or unavailable. We were invited to Miles’s birthday party in May 1986 but we couldn’t make it. By now I’d become a good friend of Gordon Meltzer [Miles’s road manager] and so Prince would suggest I call Gordon or Miles. Prince was loath to give out his number and I was one of a couple of people who would handle most of his calls. So, whenever Miles was trying to find Prince, he’d call. Sometimes I’d come back from the grocery store and there’d be this raspy voice on the answer machine saying “tell that little purple motherfucker to contact me!”

Prince

TLM: Miles and Prince met in 1987?

AL: Prince asked Miles if he could come to the studio and hang out and maybe come over for dinner. As it happened Miles was available. It was a few months before Paisley Park Studios was open and so we were working in a large industrial warehouse. I remember picking up Miles at the hotel and driving him to the warehouse and Prince was rehearsing his band. Miles hung out at the rehearsal but didn’t bring his horn – he didn’t play with the band. Miles hung out for a few hours and Prince then had Miles over for dinner. Prince invited his father, who had been a local jazz pianist. He was an extremely eccentric player – I think he styled himself as a local wannabee Thelonius Monk! Prince also invited Sheila E, who was the drummer in his band and my brother.

Eric says it was one of the oddest dinners he’d ever had! It wasn’t exactly tense, but it wasn’t exactly casual! There was so much tip-toeing. Eric says it was like two boxers feeling each other out. At one point Miles turned to Prince’s Dad and said ‘So you’re a musician too?’ And Prince’s Dad says: ‘I was a piano player but always saw myself as [saxophonist] Lucky Thompson.’ Miles replied ‘what the fuck did you want to do that for?’ and the whole table collapsed! Then Miles asked Eric ‘How do you stand when you play? Stand up and let me see.’ So in the middle of this dinner Eric stands up as if he was playing! Towards the end of the dinner Miles says to Prince’s Dad, “Now I know why that motherfucking son of yours is so crazy!” It wasn’t exactly relaxed, but there was a lot of love in the house.

TLM: Any further meetings?

AL: To my knowledge it was only their second meeting. Then we went on tour in Europe and they did, and I’ve got tons of emails from Gordon where we were trying to meet, but never did. Then in July 1987, I got a message from Gordon that Miles needed to speak to Prince urgently. Miles wanted a tape of the track “Movie Star” and Prince had decided that since Miles liked Movie Star he now wanted to do a whole album, and based on the emails I have, Prince was initiating this. This is now the middle of July 1987. I have an email from Gordon Meltzer and Peter Shukat [Miles’s manager] saying that Miles and Prince hadn’t spoken. It mentions the possibility of Miles being available to work on an album in September and October. Based on emails, apparently they did speak in August. Prince also sent Miles a second cassette of the second Madhouse album he had done with Eric. So now they’ve revived the possibility of doing an album.

Madhouse 16 – the second and final Prince/Eric Leeds album

TLM: So why didn’t it happen?

AL: Was it a case of whether Miles wasn’t seriously committed to doing a second Prince record or whether Warners didn’t want it and were trying to dissuade us? I always got the impression that Warners were lukewarm about the idea of them doing an entire album. They were more of the mentality ‘it would be nice to have Prince do a couple of songs and maybe do a vocal’ as the marketing aspects of that were so attractive. But I’m not so sure Warners were happy about the idea of Prince taking over an entire album. I always had the impression that behind the scenes they were trying to contain the relationship – they’d love to have a couple of songs but didn’t want it to go no further. But I know that Prince had roped off a couple of weeks at Paisley Park for him and Miles to work together, but it didn’t happen.

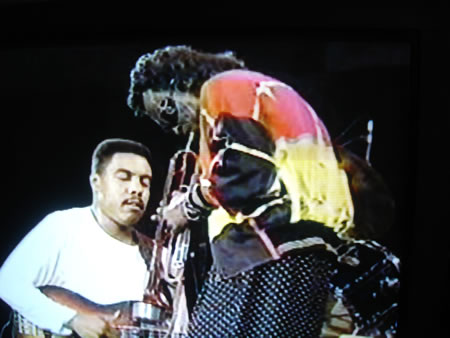

TLM: But Miles and Prince DID perform on-stage at the famous 1987 New Year’s Eve concert.

AL: It was a benefit that Prince had decided to do for homeless people in Minnesota. It was a very expensive ticket that was marketed to the corporate world. It coincided with the fact that Paisley Park had only opened in late summer so would be the first major event on the soundstage. It was a great event. At some point, it crossed Prince’s mind that we should invite Miles. Miles flew in from Europe with Gordon and Foley. They attended the dinner and he was delightful – sociable, charming. He met my parents – they thought he was the nicest guy in the world! My mum’s now 94 and afterwards she read the stories in Miles’s autobiography and said “He didn’t seem like that sort of guy to me!” He met my son Tristan and Miles signed him an autograph and drew a picture. He pointed at my wife Gwen and at me and then pointed at my son and said “You did this! You did this! That’s good work sister!” He was a delight to have.

Of course it was arranged that Miles would sit in. The upshot of this was, that like James Brown, Prince has a set of elaborate cues for his band that cue certain breakdowns and changes of tempo and so on that he will spontaneously signal. Now he might be doing a vamp and let’s say Eric is doing a tenor solo, Prince would just spontaneously feel he wants to break down and so if Eric hears that signal, he’ll know what to expect, so if there’s a change in key or tempo in the middle of a solo, he can follow it. Of course Miles had no way of knowing all this and so didn’t know what to expect. So after the performance Miles comes off-stage and says “That little motherfucker tried to set me up!”

Miles From The Park bootleg

TLM: Why wasn’t it ever officially released? The concert and video have turned up on the bootleg “Miles From The Park” and as you say, it’s a great event.

AL: It was professionally shot with more than one camera. In fact, Prince would videotape almost every performance – we’d set-up a video camera next to the soundboard – we even used to video all the rehearsals. So there’s a ton of video Prince has got in-store. He would take the tapes home and we would never see it again. There might even have been a video running when Miles was at the rehearsals [in 1987]. That was a concert that could have been issued on home video and probably should have been done. I think Prince would have seen it as redundant because it was basically the same show that we done a home video on that summer. What was known as the Sign of The Times tour was released through Warner Home Video and was a reasonably well produced video of that tour. The only thing unique about the New Year’s Eve concert was Miles’s appearance.

[Since this interview, the 1987 News Year’s Eve Concert has been officially released on DVD on the posthumous Prince release Sign O’ The Times (Super Deluxe) boxed set.]

TLM: Prince has said in an interview that he’s recorded long improvisations with Miles that he’ll release one day.

AL: I don’t buy that. I don’t know when they would have done it. It’s only in recent years he’s talked about this. Could there be recording I’m unaware of? Of course but he never talked to Eric or me about it. If it happened it would have leaked out – there would have been shop talk. Even if he had recorded it at home, he still would have used an engineer. I’m sure Prince would have talked about it and would have let us hear it – I mean he’s a guy who when he had done something that was half-finished and he was excited about it, couldn’t wait to share it with the guys in the band, the guys he trusted in the business. He would have said ‘Come listen to this.’ There’s just no way that could have happened without us knowing. There would have been some form of a record and there were so many ways that information could have filtered out, at least within the camp. I’ve had access to his tape logs – my personal assistant was responsible for logging the tapes and so every time she would record it on a weekly basis -she’d get data from the engineers to organise this enormous tape archive of his – there’s just no way that could have happened.

I tell you where I think that come from. He’d constructed a tune called “Funky.” He sent a cassette of this to Miles, What it was a rather lengthy track that Prince had constructed with samples. Is it Miles playing on the track? Absolutely, but it’s samples. Everything else on there, Prince plays. He took some samples from Miles – whether they came from “Can I Play With U?” I don’t know. It’s more coherent than “Can I Play U?” Maybe it was Prince’s way of saying ‘this is how we could do an album together.’ I just wonder whether there isn’t more material like this or if Prince is referring solely to this. I can’t imagine what else he could be referring to. I can’t prove it, but there’s absolutely no way he could have some something with Miles in the studio without one of us hearing talk of. Either we would have been physically present to see it or we would have heard about it from an engineer or we would have got a studio bill to pay and said: ‘what’s this?’ There’s no way this could have happened without us knowing.

TLM: What if it took place at Prince’s home studio?

AL: He couldn’t operate his studio at home by himself – he would have engineers on call and we would have had a record of it. And as for the night Miles went to dinner at Princes’s – Eric and Sheila are clear that he didn’t have his horn then. I don’t think he was ever in his house again.

Chaka Khan – CK

TLM: In 1988 Miles and Prince appear on the track “Sticky Wicked” on Chaka album’s CK. But other than that, there doesn’t seem to be any further collaboration between them that year.

AL: After New Year Eve Miles started getting sick a lot and we were very concerned. I know Prince sensed something. We did go to Miles’s [62nd] birthday party in 1988 New York. It was huge fun. Miles came over and sat at our table and Miles was very pleased that Prince had come. There was then this on-again off-again idea of doing something together. Then we saw Miles a couple of months later in Paris. The day we landed, Miles was playing at the Palais des Sports and we went over to the theatre. Prince came later and watched from backstage but he didn’t play. He asked me to rent a club and do an after-show party. The idea was to get Miles’s band and Prince’s band together. But Miles’s band had to pack up and move off, and our gear was still in transit. Another opportunity missed.

A couple of months later Miles came to Minneapolis for the opening of the US portion of the tour that year. We had a big party at Paisley Park. It was very much a media event – the Warner execs were there and the MTV was there. Miles came to that and was just there socially. There was a jam session that night and George Clinton was there and Mavis Staples and a few others, and they got on stage, but not Miles – he didn’t play.

Then a couple of weeks after that Miles came to our concert in Madison Square Garden in New York. So they’re seeing each other more often, but still no activity. Then in December 1988, Prince recorded Madhouse 24 that included “R U Legal Yet?”, “Jailbait”, “A Girl and Her Puppy” and “Penetration.” They were the songs that ended up with Miles. For some reason, Prince decided that it would not be a Madhouse album. Or maybe he thought this stuff would be right for Miles. We sent the stuff to Miles to hear.

Miles playing “Penetration” on “Miles In Paris”

TLM: Now we’re in 1989.

AL: In 1989 the schedule got quite erratic because it seemed like every couple of months Miles was going to the hospital for this or that. Nothing much happened. They saw each other again in April 1989, but Miles wasn’t well. In fact, Prince held a party in Paisley Park afterwards, but Miles didn’t go – he went back to the hotel.

TLM: What about 1990?

AL: I don’t have notes for 1990, so if anything happened I’m not aware of it. But through all of this, Gordon and I had the desire to make this happen and it got to the point where we were the only two left – I think everybody else had given up on it. And we kept prodding them at both ends to figure out a way for this to happen.

TLM: In 1991, Miles started playing some of Prince’s songs in concert and Miles was planning to record some of Prince’s songs for a new album.

AL: By now Madhouse 24 has been cancelled. In January 1991 Prince told Miles he could use the Madhouse stuff if he wanted to. I also have a note from Gordon that Miles was asking for more material. We had resurrected the idea of sending material back and forth in order to make an album. Now, whether the Miles camp or Warners saw this as being part of what became Doo-Bop or whether like us they were thinking of a whole album, I don’t know [Gordon Meltzer says the idea was that Miles would do a double album, with one disc being hip-hop material and a second including material from Prince]. The MO had become Prince sending stuff to Miles: “You like it, do something. You don’t, send it back.” It was pretty casual at that point.

His Last Concert In Avignon – Miles plays Prince’s track “Movie Star”

One of the things Miles wanted was an instrumental of “Nothing Compares 2 U” which Prince wasn’t keen on and thought was kinda corny just to do a trumpet on top of a song that already existed. So he said ‘I’m not going to send him the original track, let’s re-cut it and try and give it a different flavour.’ He did re-cut the song. I think Miles envisioned it as a potential “Time After Time” after Sinead O-Connor’s hit with it. Prince also asked Eric if he had anything in mind to send to Miles. Eric went into the studio with a guitarist from George Clinton’s group, Gary Shider, and they did a track that was influenced by the Agharta stuff – it wasn’t like the stuff Miles was doing. It was called “Frame of Mind” and we sent that. Nothing ever came of that. The only thing that got past that stage was the three Madhouse songs (“Penetration,” “Jailbait” and “A Girl and Her Puppy”) because he went to a studio cut those songs but I believe there’s only trumpet one of those songs and it’s more a scratch track [rough recording].

Shortly after that Miles booked to play at a club in Minneapolis that Prince owned called the Glam Slam – it was a great gig. That was the last time I saw Miles perform. It was a tremendous gig. Miles was great and it was a long set. Prince was there, although I don’t recall him going backstage. Again Prince threw another party but Miles didn’t go. But it was clear to me that Miles wasn’t in good health, even though he sounded great; his chops were in pretty good shape.

TLM: But you did see Miles again.

AL: I just happened to be in LA and had been calling Gordon about getting together for lunch. He suggested I go see Miles in hospital. I saw Miles in the hospital on 12 September 1991. I didn’t stay long. Miles looked terrible. It was a very sobering visit and I remember going back to Prince and saying: ‘it looks bad and he’s very sick, and if it works for you, say your prayers.’

***

Many thanks to Alan to sharing his time and his thoughts with TheLastMiles.com and to Alex Hahn for his help. Alex has written a book about Prince, “Possessed – the Rise And Fall of Prince.” (Billboard Books). You can order it from Amazon

Thanks also to great Prince fan sites Prince.org , Dawnation and Housequake.com as well as Prince music specialists Madhouse Music for linking to this piece.